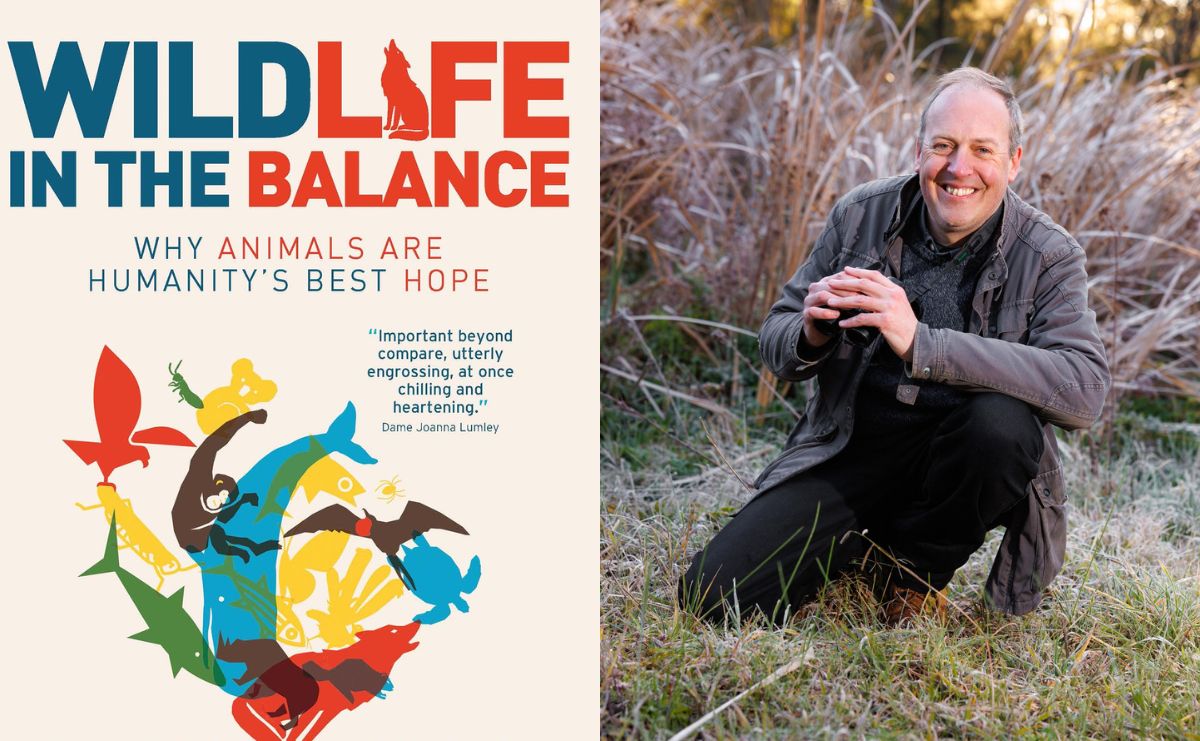

Wildlife in the Balance by Simon Mustoe is for anyone concerned about the future of our planet. Packed with scientific detail, delightful black and white drawings of anything from dugongs and tapirs to gannets, and dozens of stories that explain the science, this is a text that flips the script on how to save the planet.

Diving from scientific concepts to personal stories to an overview of the evolution of Earth, the book moves deftly from macro investigations of whole ecosystems down to microcosmic stories of tiny species and intimate relationships within their ecosystems. A symphony of science and stories that inspires and educates on every page.

The clue to the purpose of the book is in the subtitle. Wildlife in the Balance: Why animals are humanity’s best hope is a treatise on the role that animals of all shapes, sizes and species play in maintaining Earth, creating and building a planet that’s fit for human survival. Simon Mustoe is a well-known ecologist, conservationist and blogger, and he brings his three decades of travels, experience and learning to this powerful book.

The book was inspired when he was in Raja Ampat, an area in eastern Indonesia, where he has spent a lot of time diving and working, when someone asked him, ‘Why does a turtle matter?’ The question lit something inside Mustoe, ultimately leading him to ask the same question of all animals on Earth – including humans. Why does an earthworm matter? Why does a sparrow matter? Why does a humpback whale matter? And how did the evolution of these – and all other species – combine to create a liveable planet?

The intricately woven answers to these questions is the book Wildlife in the Balance, which itself is also a solution (or a tool) for restoring balance on our planet.

Throughout the book, Mustoe reiterates that we need a new way of understanding wildlife and the role all species (including humans) play. We need to recognise and remember that humans are animals too, part of an intricate web of evolved creatures who work best when they work together. The hope at the heart of this book is Mustoe’s assertion that ‘our animality is our power to make individual, everyday choices, and this has always made the difference between life and death on a planetary scale’.

We humans are some of the most powerful beings to ever exist. In this power lies both our potential for destruction as well as our ability to adapt.

Regardless of this potential, in the past four decades, we have pushed three-quarters of all species into extinction. The loss of these species is not only a tragedy because they’re gone, but also because their loss impacts our own chances of survival. Looking back through the different epochs of Earth, Mustoe demonstrates that ‘Homo sapiens was the latest in a long line of animals that was likeliest to survive because that was the outcome that stabilised our planet’s biosphere at the time’.

We exist because the animals we share the planet with existed, breathed, ate, defecated, bred, and ultimately built the ecosystems we rely on for food, climate control, drinkable water, and reliable weather.

Mustoe’s experience working and travelling in diverse ecosystems, as well as his scientific knowledge and insight, make Wildlife in the Balance both interesting and educational – with ‘a-ha’ moments on every page. There is also urgency throughout the text, and the need for immediate action is evidenced in the extraordinary scientific data that Mustoe includes from the disciplines of biology, zoology, ecology, conservation and beyond.

He argues his points with energy, even if at times the key themes are repeated. The book could have been a little shorter if Mustoe hadn’t repeated his central points again and again. However, the repetition does lead to a deeper understanding, which is possibly the reason for the reiterations.

One way in which Wildlife in the Balance is different from other conservation texts is Mustoe’s modest stance on plants. While he acknowledges that there is ‘an urgency to protect nature’, especially wildlife-rich ecosystems like those in Indonesia and Australia, Mustoe does not necessarily advocate for planting more trees. In fact, he says, there is more tree coverage now than 35 years ago.

His focus is instead on the importance of returning animals to the remaining ecosystems. He adds, ‘grasslands and oceans aren’t enough on their own without wildlife’. It’s not enough to plant more trees or mangroves or kelp forests; we must also retain, support and (where possible) reintroduce the wolves, whales and worms that balance these ecosystems.

Although the book is filled with examples of how humans have messed up a perfectly functioning planet, it is also a delight to read, especially when Mustoe takes us on a deep dive (sometimes literally) into the world of a specific animal. Take this exquisite passage where he describes diving in Raja Ampat in Indonesia:

You begin to feel miniscule after you dip into the otherworldly mysteries of Raja Ampat. It’s like diving inside a gigantic living organism; navigating through its nervous system, riding the rush of currents passing down networks of ancient channels, highways for cells and plankton that feed its organs: reefs and ocean fronts where miniature forces combine on a massive scale, giving and supporting life.

There are astonishing claims in this book, and Mustoe takes time to explain and clarify the science. For many people, this book will give you new ways of seeing the solutions to our collective problems. Indeed, Mustoe believes that most of our issues – including pest plagues, famine, climate change, drought, pandemics and extreme weather – can be partially or fully resolved by reintroducing animals into ecosystems and ensuring the optimal conditions for them to survive and thrive. But he insists it’s not easy and some of the ecosystem recovery that we need could take decades due to the growth and breeding cycles of animals.

A word to the non-scientific readers: a central concept that Mustoe refers to throughout the book is the science of entropy; at times I found it challenging to wrap my head around this concept, but Mustoe’s examples go some way to clarifying why entropy matters in the context of the book.

He says, ‘Entropy is how energy flows through the universe. It’s the reason why time can’t run backwards and why, when you break an egg for breakfast, the egg remains broken rather than turning back into an egg.’ Yep. A head scratcher. But worth the effort.

Regardless of the challenges of our times, Mustoe asserts that we have the benefit of years of scientific research, failed experiments, knowledge, and understanding – and now the willingness to listen to Indigenous peoples – that will help us restore the balance. We have the best chance ever to survive and change the slide towards extinction for the Earth’s remaining species – including us humans.

Wildlife in the Balance: Why animals are humanity’s best hope

By Simon Mustoe

Publisher: Wildiaries

ISBN: 9780645453508

Format: Paperback

Pages: 345 pp

Publication date: October 2022

RRP: $34.99