The haste with which performing arts fixture and legend Circus Oz is being wound up and consigned to distant memory, as if there were nothing more to be said, is just one disturbing aspect of a situation bristling with unanswered questions.

The Board press release is written in the depressingly familiar managementese used to cover up blood on the carpet:

The government review identified that Circus Oz has a tremendous rich legacy but there were systemic issues holding back the company. It was recommended that if [it] is to continue to receive public funds, reforms were required to introduce an entirely skills-based board and broaden the membership criteria to diversify representation.

‘Systemic issues’ relates to the company’s (supposedly bad) governance, rendering it unfit to receive public funds. The ‘reforms’ proposed by an ‘independent’ review – one instigated by the Australia Council and Creative Victoria, and endorsed by the Circus Oz Board – seek to change that governance. The Board decided to frame them as an all-or-nothing ultimatum. Put to a members’ vote on 8 December, the response – unsurprisingly, given the history of the company – was a resounding ‘no’. The board then decided to close the company (rather than discuss the problems further or resign themselves).

When a cultural organisation of long-standing finds itself on the brink of extinction, there are always complex issues at play, and arguments to be heard on all sides. But claims there has already been ‘comprehensive internal assessment’ should be set aside. A sponsored investigation predisposed to affirm the managerialist predicates that rationalise its own authority is not the same as open and public debate among all stakeholders.

Perhaps it’s conjunctural. In the current, single-leader-obsessed climate, arts companies are vulnerable when they have no Artistic Director, and Circus Oz have been without one since the departure of Rob Tannion in 2019 (to boot, its General Manager, Tahilia Azaria, is on maternity leave). And the knives are quickly out for any organisation that hits a flat patch with its shows. Worthy talk of ‘the right to fail’ is just that – talk.

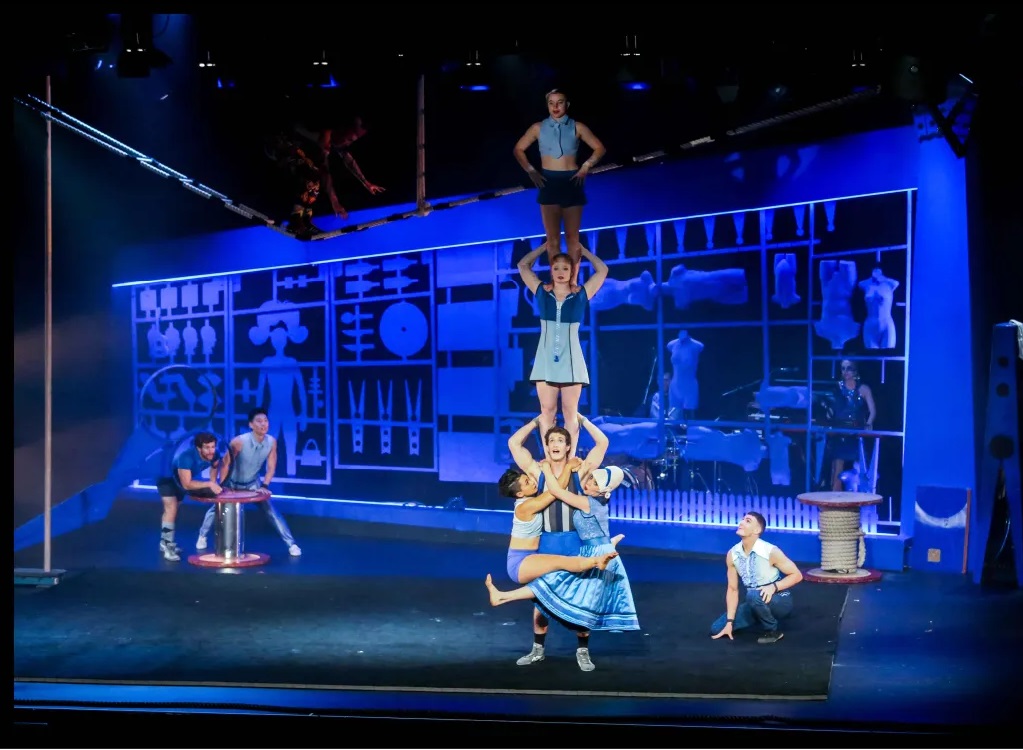

In 2018, Circus Oz was celebrated for its ‘political savvy, entertaining, and polished work’ and for ‘mov[ing] into a new purpose-build space in Melbourne, increas[ing] its international profile, develop[ing] important initiatives such as the BLAKflip training program for young Aboriginal performers and uphold[ing] its 40-year commitment to politically driven circus, diversity and gender equality’. Four years later it’s toast; and two of these years have been COVID-affected ones.

In an eroded funding environment, with ever-dwindling public assistance for ever-increasing creative output, organisational implosions tend to exacerbate existing tensions (like generational ones) and prompt cannibalisation of the sector. Artists turn on each other. For those with good memories, the Circus Oz crisis parallels the demise of Anthill Theatre in 1994, and the failed conversation with funding bodies that precipitated it. More recently, controversy about the role of boards in Black Swan and Barking Gecko indicate similar conflagratory tendencies. In each instance, the administrative apparatus designed to protect arts companies ended up doing significant damage to them.

DEEPER ISSUES

The Circus Oz crisis, we suggest, has deeper roots, and requires more than nostalgic mourning for a defunct youthful anarchic idealism. Company members are right to want to inquire into the 28 ‘significant structural reforms’ rather than accepting a role as a bunch of Baby Boomers incapable of change. The proposed ‘reforms’ are part of a long wave of professionalization-nee-corporatisation of board oversight that began in the 1970s, and intensified in the 1980s and 1990s (Julian discusses this history in detail in Australian Theatre After the New Wave: Policy, Subsidy and the Alternative Artist).

Is there any evidence these changes have made arts companies, and the artists who work in them, more successful? Presenting to the Adelaide Reset Conference in November, arts consultant Kate Larsen was withering in her assessment of current governance approaches:

Australia’s not-for-profit governance model takes a team of unpaid or low paid volunteers and puts them in charge of a team of paid experts. Many … have little or tangential experience. Most have never run comparable arts organisations. And … most … don’t understand the difference between what the legislation requires them to do, what they want to do, [and] what the organisations need from them.

The arrogant dismissal of the right of artists to be central to the operation of their companies systemically skews accountability processes. A ‘skills-based board’ is a cypher for ‘business skills’; not just financial skills but the capacity to treat artistic creation as a business, to identify new markets and areas of growth, and reconfigure arts companies accordingly. This includes the “flexible” use of labour (temporary and zero-hours contracts and outsourcing) and top-down management, where expressions of non-competitive collegiality are suspect. A ‘skills-based board’ is one able to apply a corporatist governance model.

Given Circus Oz’s history of worker control, there is little doubt an example is being made of it. As Justin McDonnell recounts in Arts, Minister?, when the Australia Council introduced early versions of board ‘reform’ in the late 1970s it engaged in a fiery stoush with the Australian Performing Group (APG) over its collective management structure. Circus Oz has its origins in the APG. Company Treasurer, Mike McCredie has made it clear it is less the idea of artists on the Board that is objectionable, than that it involves a quota (4 out of 11) and they must be drawn from the membership. Using a phrase from union-bashing days of yore, he dismissed it as ‘a closed shop’. Further discussions with the company were futile. ‘We gave them that binary. They understand what the vote means.’

There are parallels here with Australian universities, where changes over the last three decades have likewise removed academics and students from key accountability bodies. In an age of capitalist realism anything that does not conform to a corporatist view is an unwanted challenge. There’s nothing apolitical about arts governance. Wobbles at the box office become useful cover for removing something historically recalcitrant.

The Circus Oz crisis is an occasion to ask what we want from the oversight of our arts bodies, what models – the plural is key – should be promoted, and what is involved in insuring they work in the interests of the arts. ‘Reform’ is typically spun as a long-overdue update, more efficient and user-friendly. But behind the rhetoric are one-size-fits-all accountability processes. The Circus Oz Board and some in the media might want to present the crisis as fuelled by ‘the selfishness of an older generation’, indulging themselves at the expense of younger artists. The reality is the escalating corporatisation of governance structures. Under the mantra of increasing diversity, ever fewer artists are appointed to boards. Circus Oz performer Mitch Jones has said:

I don’t want to be on a board, I want to make art. The idea of the company as a social experiment is a lovely bit of nostalgia, but is also from a different political era.

In an time of First Nations First, Black Lives Matter, #metoo and fossil fuel divestment, this is a frankly incredible statement. Sitting on an arts board is as much a part of being an artist as making art. Not all artists choose to sit on boards. That does not mean they should not do so, or worse, be considered unsuitable for such roles.

In recent years, new initiatives involving workers control, co-operatives, and locally-owned community businesses have grown up across Europe, and in North and South America. Expanded participation, cultural democracy and citizen assemblies abound. There is a rich variety of different oversight models to choose from. Not for the last bastion of neoliberal groupthink, arts governance in Australia. While ‘accessibility’ and ‘accountability’ are a constant refrain, ‘democracy’ is barely whispered.

The corporatisation of arts boards was well-documented by Judith White in her book Culture Heist in 2017, and it has gotten worse since. Though many board members seek selflessly to ‘give back’ to the arts, this does not alter the corporatist worldview by which they try to save artists from themselves.

Less selfless board members enjoy the resulting cultural capital, and the networking opportunities provided by gala performances. For in an ugly segue, the expanding corporatisation of the arts overlaps with the grace-and-favour system by which the Coalition Government now rewards its supporters, from rorts in sports clubs, car parks and community grants, to the stacking of public bodies, weaponised by a culture war mentality.

The Circus Oz crisis plays out against the backdrop of the continued marginalisation of art and culture in Australia, stretching from the ABC to the university sector. The refusal of company members to relinquish their cherished democratic principles looks like a much-needed act of resistance. In one sense it really is a brutal either/or choice: will the crisis spark real change, or do we just fall in behind the corporately skilled?

About the authors:

Dr Tully Barnett is a Senior Lecturer in Creative Industries at Flinders University, and an ARC DECRA fellow for a project on Digitisation and the Immersive Reading Experience. She is a Chief Investigator on the second Laboratory Adelaide: The Value of Culture project with Julian Meyrick and Robert Phiddian, with whom she is co-author of What Matters? Talking Value in Australian Culture (2018), investigating the way value is understood through formal and informal reporting practices. She is the Deputy Director of Assemblage Centre for Creative Arts.

Julian Meyrick is Professor of Creative Arts at Griffith University. He is Literary Adviser for the Queensland Theatre and General Editor of Currency House’s Platform Paper series. He was Associate Director and Literary Advisor at Melbourne Theatre Company 2002-07 and Artistic Director of Kickhouse theatre 1989-98. He has directed over 40 award-winning theatre productions and published numerous books and articles on Australian arts and culture.

Justin O’Connor is Professor of Cultural Economy at the University of South Australia. He was a UNESCO expert for the 2005 Convention on Diversity of Cultural Expressions and has just published Red Creative: Culture and Modernity in China.