Dragana Radakovic (Turandot) and Riccardo Massi (Calaf) in Handa Opera on Sydney Harbour. Photo: Prudence Upton, supplied

Turandot is best know for a lingering B – a note made famous by the Italian tenor Luciano Pavarotti and his rendition of the aria Nessun Dorma. Without it, one might argue that Puccini’s last opera is dramatically a little thin, making it an unusual choice for Handa Opera on Sydney Harbour this year.

But there is enough bravado, spectacle and recognition in that one B to hold the Harbour event.

It is not surprising, then, it offered “the fireworks moment” wrapping up the first act and ushering in Puccini’s big number.

But heights were not reserved for notes and fireworks alone.

The opera opens with Mandarin (Gennadi Dubinsky) entering via an enormous construction crane that suspended him over the stage and out over the audience. It hinted at a modern China and its puppetry of officialdom.

Gennadi Dubinsky was unwavering despite singing at great heights; picture ArtsHub

The crane was again used to elevate the Emperor over his subjects, seated on a kind of half-throne-half-royal balcony that almost swallowed David Lewis in the role.

The real magic was their absence of vertigo.

While the throne was not entirely successful – a little clunky, light on bling, and its scale slightly confused – the use of vertical layering by Designer Dan Potra was spatially adroit, compensating for the lack of the usual theatre scrims, set changes and flys.

Bringing movement into the otherwise static set seemed a priority for Potra this year. An impressive carved dragon breathed fire (we wanted more), its winding body morphed into the Great Wall and acted as a screen for projections created by Leigh Sachwitz.

It was a fantastic addition that added dynamism and narrative, assisting audiences to navigate this opera’s frosty emotional quagmire.

Sets and costumes by Dan Potra; Photo ArtsHub

The other dominant element of the set was a lofty pagoda from which the vindictive Princess Turandot held her aloof and icy stance.

While the structure was extremely effective and responsive to Scott Zielinski’s lighting design, the mechanics were clunky and tenuous. Its in-built draw-bridge that delivered soprano Dragana Radakovic to the stage incited fear not in Turandot, but fear for her perilous descent.

Overall, the production was not as gaudy or confused as last year’s design for Aida – its dancers decked in faux latex leather strides with a quasi Nazi feel were replaced by chorus in fine layered costumes and dancers with billowing sleeves aka “human streamers” both responding beautifully to light, movement and wind.

It should be said that the costumes were superb, sensitive and with their lightness of fabric well thought for the setting.

The weather gods added to the experience on opening night, reminding exactly why Opera on Sydney Harbour is a brilliant success.

This year – for its fifth edition – Chinese surtitles were added, catering more to a growing Chinese tourism market rather than a reflection on the choice of Opera.

Chinese-American Director Chen Shi-Zheng was at the helm of this new production. His reticence to directing both Turandot and Madama Butterfly for their ‘stereotypical portrayal of Asian women’ was won over by the Sydney location.

Which brings us back to that B and its bravado.

We have been nurtured to expect showmanship with that infamous note, and on opening night Italian tenor Riccardo Massi delivered with depth and power, but one more in-keeping with Puccini’s intention rather than Pavarotti rendition.

Delivering the role of Calaf (shared by Arnold Rawls), Massi was a little stiff in the first act but relaxed into the role by the time he coaxed the icy Turandot from princess to mere mortal, slightly outshining the diva.

Serbian soprano Radakovic had an imperious presence as Turandot, steely and imposing in her projection. But it felt a little too cold, too brittle, between her elevation and amplification. Perhaps that is the perfect Turandot, a woman who persists in killing her suitors? Chen wanted to make her “real”, to project new understanding into Turandot of a China with foreign interest and dreamed futures jarring against a steadfast embrace of history.

Radakovic shares the role with Daria Masiero.

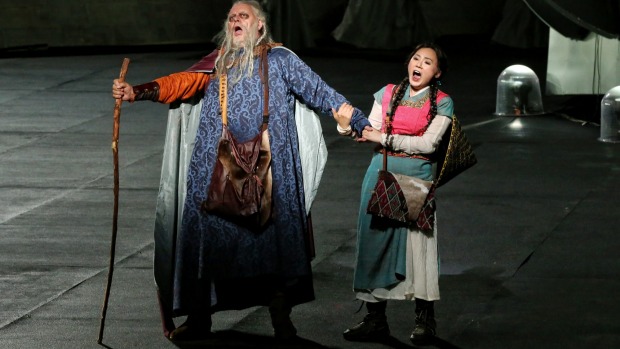

The soprano who stole the night for this writer, however, was Hyeseoung Kwon in the role of Liu. Seasoned in the role, her voice was sweet and yet had the strength to rival Radakovic’s glory.

She captured great emotion as Liu, nailing the blend of simplicity with pathos; love and fear; tenacity and tenderness. Plus she does a great dying scene of self-sacrificed for love. She clearly captured the audience on opening night.

Conal Coad, left, as Timur and Eva Kong as Liu in Turandot. Photo: Prudence Upton

As the aged Timur, Conal Coad also delivered a tender support role, his dramatic skill bolstering his presence in the opera.

The trio of Ping, Pang and Pong (Luke Gabbedy, Benjamin Rasheed and John Longmuir), in contrast, felt a little thin. The trio is meant to offer comic relief to the tragedy, but it sits uncomfortably within a Chinese court context.

The three had an energetic role at Chen’s hand, constantly moving across the set and changing costume to try to build that energy – Potra trying to pull as much out of their role through costume and set.

Overall the sound quality was much better – more balanced and less bassy – this year than the past two.

The well-liked Brian Castles-Onion returned as conductor, his experience of the challenging setting put to advantage.

Just like the words Nessun Dorma hail – “none shall sleep” – it would seem that many have been working overtime to move through past criticism of the perennial opera – and it shows.

An Opera on Sydney Harbour is always going to be about crowd-pleasing spectacle, and there will always be compromises due to the setting. But the gains can be argued as far greater, taking opera to new audiences and reinvigorating a passion for the dramatic medium.

Simply, Turandot does deliver.

It is a spectacular event, both on stage and the pomp surrounding it, and remains an annual highlight not to be missed.

Rating: 4 out of 5

Turandot: Handa Opera on Sydney Harbour

Stage director and choreographer: Chen Shi-Zheng

Designer: Dan Potra

Projections: Leigh Sachwitz

Lighting: Scott Zielinski

Conductor: Brian Castles-Onion

Sound designer Tony David Cray

Mrs Macquaries Point, Sydney

24 March – 24 April

opera.org.au