The last major exhibition of Henri Matisse’s (1869-1954) masterpieces that travelled to Australia was in 1995. Today, 26 years later, our world is a very different place, and an exhibition that ushers visitors through a message of ‘Life and Spirit’ is very much on point, as we hanker for that very palpable rush of wonder that Matisse can offer.

But while a pandemic may have triggered us to better appreciate the joy that art can bring, this exhibition has also been framed to place one of the world’s great modern masters firmly in this region as a point of influence.

Presented in tandem at Art Gallery of NSW (AGNSW) with Matisse Alive – where curators have invited contemporary Australian artists to pay respect to Matisse’s Pacific oeuvre – this blockbuster from the Centre Pompidou in Paris taps into a much more contemporary lens that museums of our times apply when considering collections from a past.

This is perhaps no better articulated than in the first room that viewers encounter in Matisse: Life & Spirit, which ushers them across that threshold of change, and the first years of the new century (1905-1907) when Matisse’s turned from academic training and take a rampant dive into colour and form – which saw him labelled a Fauvist.

The trigger – it was travel – is something we have all had pause to rethink of late.

This room captures a sense of search and anxiety, one that we can immediately connect with as an audience. Here are paintings from his first trip to Algeria in 1906, the south of France, and Italy in 1907. What this movement does is give Matisse permission to break out, and we see the first glimpses of decoration which was to become signature to so much of his later work.

The tone changes quickly however, with the next room, and viewers witness Matisse’s struggle with the impact of Cubism and a brewing World War. There is a great sense of the interior here – lots of windows positioning the viewer looking out (sound familiar?), but also some incredible surprises for the viewer with paintings such as White and pink head (1914) and French window at Collioure (1914).

An absolute gem in this room is the painting Interior, goldfish bowl (1914), where we see Matisse first embrace that iconic blue of his for the first time; the sky, the River Seine and a fishbowl a briny spatial blur.

This level of consideration continues in the next room, where it was not travel nor war that marked the chaptered decades of Matisse’s career, but rather a parallel path as he sought to reconcile a visual relationship between painting and sculpture.

Rarely shown together is a suite of bass relief sculptures from 1909-1930, Back I-IV, which Matisse would work on then put aside, then revisit in the attempt to reconcile the life-sized form. These were done in the background of some of his largest painting commissions, including Dance and Bathers.

What this journey through the Backs series illustrates is the tenacity of an artist to work over and over again on a form, pushing it from convention to abstraction. It is not surprising that Matisse is often referred to as an ‘artist’s artist’.

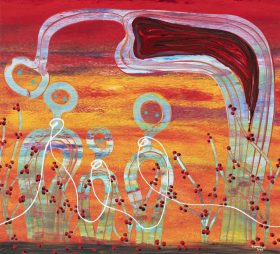

Central to this room is a suite of small bronze busts of Jeannette and Henriette, which connect with paintings – among which is perhaps Matisse’s most loved Decorative figure on an ornamental background (1925-26) – pictured top – and painted at that moment where he relished decoration.

The next chapter again signals a new decade and another change – a period of experiment to rejuvenate his practice. We see some particularly sparse canvases here that will surprise many Matisse fans.

Co-curator of the exhibition, AGNSW’s Jackie Dunn describes it as ‘a moment of pause for Matisse testing himself’, adding that ‘we can see the shift in his practice decade by decade.’

This period saw Matisse return to drawing, and to push the work into a kind of architectural space. It is not surprising then, that visitors next encounter a suite of works in a gallery that has been mapped out to footprint the living room of Nelson Rockerfeller’s apartment in New York – with his prized The Song (1938), painted over the fireplace – brought to Sydney in a rare inclusion – as a centre to this space.

In his room you see some of Matisse’s last canvases before he had that terrible operation for cancer in 1941, which was to again turn his career on a pivot. An iconic work that has made its way to Sydney is Large red interior (1948).

Architect Richard Johnson, who has done a super job with the exhibition design, has then turned that central downstairs gallery of the AGNSW into an evocation of the Chapel of the Rosary at Vence (France) – the incredible commission he took on in 1948. The marquettes of the stained glass windows held in the Pompidou Collection have travelled.

It is especially a rare moment given that the Chapel itself is such a hideously difficult destination to pilgrimage to. You have to take your time with this room and let it build on you; it could easily be overlooked with the swag of painted greatest hits across the show.

And every bit worthy of its blockbuster tag, the exhibition concludes on an incredible high. At polar ends of the room are Matisse’s Blue Nude of 1952 and The sorrow of the king from 1952, with his suite of jazz cut outs and two mind-blowing expansive cut out works, Polynesia, the sky and Polynesia, the sea (1946).

This is the largest collection of Matisse’s cut out works to be shown in Australia.

What many don’t realise is that Matisse played violin every day. That passion for movement, music, pause and flow is amplified across this incredible room of work. As the title of this exhibition prompts, it is full of life and spirit, at moments subtle and others joyously bold.

Co-curator Justin Paton describes: ‘There’s a wonderful cadence of self-renewal and self-questioning that runs through this exhibition.’

With blockbusters, we have been tutored to expect those fridge magnet or postcard moments – the images we have lived with in 9x12cm scale blu-tac to the wall, to then encounter in real life as old friends.

This exhibition delivers those moments in doses. But it does more. The timing of Matisse: Life & Spirit is in some ways a lucky win. To witness Matisse’s own journey through trauma, through uncertainty and reinvention and to land on such a high point in his latter years, is the inspiration and affirmation for us all now that life indeed comes in cycles, and we are on the cusp of leaving 2020-21 behind.

Matisse: Life & Spirit Masterpieces from the Centre Pompidou

Art Gallery of NSW

20 November 2021 – 13 March 2022

Co-curators: Centre Pompidou curator of modern collections, Dr Aurélie Verdier, with Art Gallery of NSW head curator of international art Justin Paton and special exhibitions curator Jackie Dunn.

Ticketed.

The exhibition is part of the Sydney International Art Series 2021–22, presented by Destination NSW.