Established in 1954, Overland is an intellectually charged Australian literary journal published quarterly in Melbourne; issue #211 is the popular journal’s publication for the 2013 winter season.

As well as a print edition, Overland also distributes articles online, with new content uploaded to its website on a regular basis. In his editorial in this issue, Jeff Sparrow notes that ‘Print remains the preferred format for most poets and creative writers in Australia. That may, of course, change but for the time being most authors want a physical copy of their work.’

Overland’s contributors should certainly be happy holding the latest issue of the journal, which contains a versatile collection of literature, including poetry, memoirs, fiction and some truly fascinating non-fiction, covering everything from bodybuilding to crowdfunding, and homelessness to the fraught pay-rates of the publishing sector.

In ‘Pump’, Stephanie Convery reflects on bodybuilding and physicality. Her writing is personal and engaging and her words drip with enthusiasm as she explores the bodybuilding phenomenon, in particular touching on the taboos of muscle and sexuality, including the stigma of enhanced musculature in the gay sex trade throughout the 1970s.

‘A builder’s body was his primary focus – and his biggest asset. It’s not clear how many bodybuilders were involved in the sex industry, but reports suggest it wasn’t unknown for a guy to duck off for a couple of hours between sets to shoot a skin flick or pose for a gay magazine. In 1972, when entrepreneur, bodybuilder and occasional porn actor Ken Sprague bought Gold’s Gym, changed its membership policy and opened its doors to the public, the already flourishing side-trade in sex became even more prevalent.’

Especially attractive is Convery’s exploration, from a feminist viewpoint, of what it means to be a woman who deliberately practices a sport that defies conventional standards of beauty and femininity.

‘In a weird fashion, the masculinity of bodybuilding means pushing feminine tropes to the extreme. An almost-pathological obsession with body fat, for example, is usually understood as quintessentially womanly. Yet no-one diets as hard as bodybuilders … What, then, to make of female bodybuilders? What happens when women take on an activity in which men have masculinised femininity?’

Alison Croggon believes that a name is a spell – ‘if someone names you, it can be a collar that fits over you, and it can lead you into a different reality, one in which you might disappear.’ In emotional prose, Croggon carves out a poetic reflection on experiences of homelessness, and the negative connotations of prejudice and social labels.

‘Watching a documentary on homelessness many years later, I realised that I had indeed been ‘homeless’. I felt a physical shock, as I have every time my life has suddenly fitted into a category. There is a violence in being named, as if suddenly your own experience transforms its nature.’

Also in this issue, Jennifer Mills and Benjamin Laird discuss the perks and difficulties of writing as a career. Should writers work for free, in a time where financial difficulties for creatives are paramount, and industry exposure of any means is consistently sought-after? Given that many publications are unable to financially compete for writers and audiences in a market bombarded with commercial media, many creative writers today rely on income from other sources. Mills and Laird chat about the possibilities and alternatives.

On a related note, Anwyn Crawford analyses the practice, benefits and consequences of crowd-funding art. For the Australian crowd-funding platform Pozible, there exists a consumer mindset, and Crawford makes the valid comparison of the mechanism of pledge and reward to that of contemporary notions of customer service. The Pozible model certainly enables artists to easily navigate and test their market, and reach thousands of people at once. More opportunities for financial support are available at the click of a mouse. However in her article, Crawford puts forth a pressing question: what happens to works of art that don’t align with the Pozible model?

‘Crowdfunding benefits projects that are snappy, simple, ‘relatable’; projects with a well-articulated and easily envisioned end result; projects that go with rather than against the current of truncated digital attention spans and rapid publicity cycles. But there is a lot of brilliant art that is not of its time, but rather before, sideways or stubbornly oblivious to it. There is art that is conceptually difficult or thematically confronting; art with no material outcome; art that has an ambivalent or possibly even antagonistic relationship to an audience. I don’t see art like that standing much of a chance inside the crowdfunding model – so where else can it turn?’

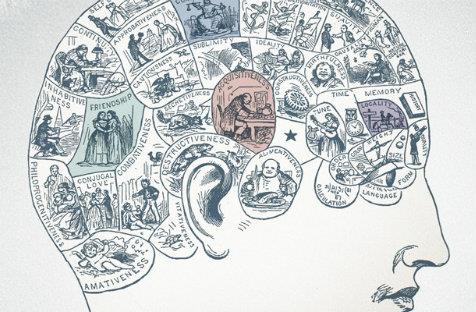

Essentially a gathering of ideas in print, interspersed with poetry and prose, Overland #211 manifests itself as a delightful collection of food for the mind. Harbouring an absorbing collection of musings on culture, the journal continues to deliver the essence of postmodern literary intellectualism.

Rating: 4 stars out of 5

Overland #211 Winter 2013

Edited by Jeff Sparrow

Paperback, 95 pp, $19.95

Published by the OL Society Limited