I knew not his name, nor where he lived, nor where he came from. But I did know his profession: some sort of stage hand or sound technician person. You know the type, those men (they are usually men for some reason) who sit behind their glowing and flashing sound desks, and make their way onto stage pre-show and during the interval to flick a few microphone or power cords about, and place said microphones in the required spots. (Although one never sees the ABC Classic FM live recording crew do this, mind you – and one must see the results of their handiwork every second or third concert.)

This particular sound technician had some special work on his aural plate for the afternoon, for there were two points of interest for him. First, he had to set up (although it was done before we entered) the speakers for the keyboards (more on that later). Second, he had to set up a microphone on its stand near the conductor’s podium.

And what a special concert this was for the sound technician, for who was to talk into this microphone but none other than John Adams, composer and conductor extraordinaire! Perhaps one of the most recognisable musical names to come out of America in the last couple of decades (not counting Lady Gaga and the like) – with works such as the operas Nixon in China, Doctor Atomic, and the very controversial The Death of Klinghoffer, among, as they say, many others – he was to conduct four pieces in the Concert Hall with the Sydney Symphony; two of his own, one Beethoven, and one Respighi. He’d just finished conducting the Beethoven and his first piece before the interval, and was coming back to give the world premiere of a new work of his, and thought some words of explanation might be in order. The sound technician, having spent the last five minutes of the interval shuttling back and forth setting the microphone up, no doubt was confident that Adams would be able to impart his wisdom and private insight to the Concert Hall at large. He was wrong.

The microphone didn’t work, you see. Thankfully, Adams has a booming enough voice that he could be heard by most with a little straining of the ear drums, and so we were treated to the story of how his Saxophone Concerto came about. That done, he retreated to his podium, while the sound technician – suitably abashed, one might think (I would not have been in his situation for the world) – scuttled across the stage, retrieved the malfunctioning microphone, and made his way off again as the audience applauded him. I’d like to think that most of the applause was just a bit of fun – the audience applauding the ‘crew’, as it were – but I wouldn’t be surprised if there was a bit of sarcasm to it in some members of the crowd. The mob can be vicious.

Sound problems aside, though, this was a wonderful concert, one that went for 15 minutes more than the usual two-hour mark. (I, however, did not care for once.) We began with Beethoven’s Fidelio: Overture, in what was quite a forceful interpretation by Adams, and quite a stately one too. He didn’t quite, to my mind at least, escape the black hole problem that many an overture at the start of a concert seem to get sucked into – that is, inspiring in the audience a want for the loud and fast parts, and a lack of patience for the rest – but he did better than most in overcoming the issue. And then we heard Adams’ Violin Concerto.

The sound technician no doubt was called upon for this too. On the left hand side of the stage, just a bit further up from the harp, there were two keyboards with a relatively small speaker (compared to those that always hang from the ceiling) behind each of them. They were, from what one can gather in the program, synthesisers, or keyboards set to synthesiser. (One has fond childhood memories of fiddling around on the keyboard with each of the instruments it lets you mimic.) The program tells us that the piece is a ‘concert work, but one composed in the knowledge that it would also be danced’. It is a piece that has had ‘more than 300 performances’, and in 1995 it ‘won [Adams] the Grawemeyer Award’, which is, as every program that has ever mentioned the award has told me, the ‘Nobel Prize for composers’. (The last Grawemeyer Award piece that the Sydney Symphony played, from memory, was Brett Dean’s The Lost Art of Letter Writing.) It was premiered in 1993, yet this was, interestingly enough, the Australian premiere of the work. (The program has a little table that lists all the Australian premieres the Sydney Symphony have given of Adams’ work; 11 in total, with three co-commissions, and one world premiere.)

It was good, but not particularly great, I thought. Or rather there were great moments in it, but as a whole it isn’t the most amazing work I’ve heard. And there is no excuse for it, either – the composer is conducting, the violinist, Leila Josefowicz, has made it one of her calling cards, and the Sydney Symphony were playing at their best, lifting as they so wonderfully do for special occasions.

The opening movement ([tempo: crotchet = 78]), where the violin basically doesn’t stop playing (nor does it for the rest of the piece), is somewhat exploratory. It captures the attention instantly, but the violin is such a busy presence that the attention wavers slightly. A slow cadenza transitions into the second movement (Chaconne. Body through which the dream flows), which is the highlight of the work. Adams talks in the program of ‘the duality of flesh’ that the describing phrase – taken from a poem by Robert Haas – suggests to him, as if ‘the violin is the ‘dream’ that flows through the slow, regular heartbeat of the orchestral ‘body’’, which seems as good a way to describe it as any. One gets a bit of the distinctly American feel that an Edward Hopper painting can create, and the perfect tranquillity (with a few less tranquil bits) of it is marvellous. There was an unmistakeable and powerful beauty to it that was most welcome. The third movement, Toccare, is a highly inertial affair, and its momentum kept the interest where the first movement didn’t quite. Josefowicz herself was an energetic bundle of energy on stage, and gave a fine performance.

The interval came, John Adams shouted a bit, and we were treated to the world premiere of his Saxophone Concerto, written for Timothy McAllister and performed by him. The program quotes a tweet of McAllister’s (how often do you see tweets in music programs, I wonder?), that describes the piece as ‘breathtaking…literally…30 minutes long! Imagine Stravinksy, Bernstein and Stan Getz sharing a taxi.’ (Who gets to sit in the front seat?)

I had precisely the same problem with this concerto as I did with the violin – the first movement (or the first part of the first movement – this follows a three-movement structure but is only in two official movements) was the least, I thought. But the difference was that the attention never wavered in this, and faults weren’t so much faults as merely less brilliant sections. Again it was the slow section where the powerful beauty was to be found, but the timbre of the saxophone was so well suited to the style of music that I think the beauty was to be found everywhere. McAllister is a fine player, too, and pulls a melancholy out of his instrument that some in the audience (included this critic) may not have immediately expected. It wasn’t the greatest of great works I’ve ever heard, but it was immensely satisfying, and if the Violin Concerto is so popular, one can imagine the Saxophone Concerto will be popular too.

The final piece for the afternoon was Respighi’s Pines of Rome – Symphonic Poem, which smacked of the type of piece tacked onto the end of a concert to make sure an audience enjoys itself – and there is nothing wrong with that, especially with two modern pieces on the program – but this performance was so much more than orchestral bluster to sate the audience. Adams seemed the perfect conductor for the piece. What distinguished it from other performances, most particularly, was the perfect pace of its slower sections (just like the Adams’ concertos). Unlike the overture, one was not waiting for the volume to be turned up; rather there was a full engagement with what was on offer in the present. Adams can get a more than pleasant sweep and trembling out of the strings, you see, which served the work well. The prolonged crescendo of the last movement was handled superbly, too, with David Drury up in the organ chiming in, as well as brass behind the boxes. It was a machine kept in perfect control, and was the best work of the afternoon. An unforgettable concert.

Rating: 4 ½ stars out of 5

John Adams Conducts Adams

Sydney Symphony

John Adams (conductor), Leila Josefowicz (violin), Timothy McAllister (saxophone)

Ludwig van Beethoven – Fidelio: Overture

John Adams – Violin Concerto

John Adams – Saxophone Concerto

Ottorino Respighi – Pines of Rome – Symphonic Poem

Concert Hall, Sydney Opera House

22 August

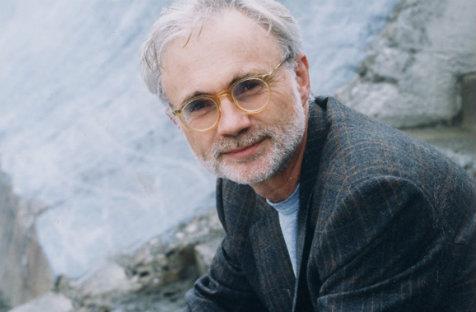

(Pictured: Composer and conductor John Adams)