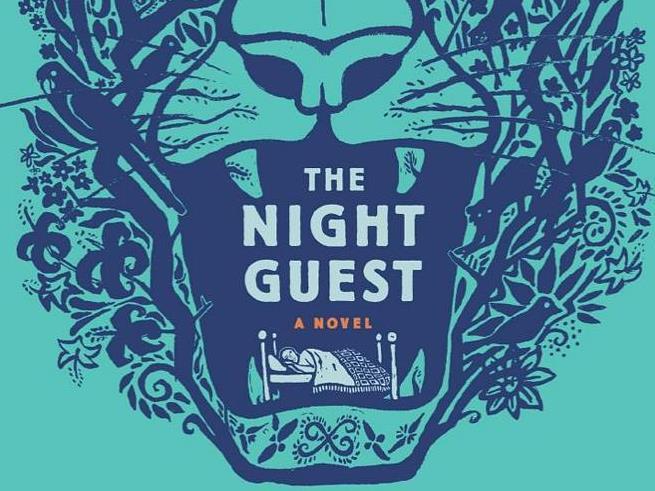

Fiona McFarlane taps into the needling cultural fears, insecurities and degradation of old age in her Stella Prize shortlisted novel The Night Guest. Reflecting issues concerning Australia’s ageing population, McFarlane’s debut novel tackles questions of dementia, culpability and independence in a beautifully spun tale grounded in recollection, a fast unravelling mind, an ominous stranger, and, of course – a tiger.

Narrated in close third person through widow Ruth Field’s eyes, the novel begins by observing her largely solitary life in an isolated beach house by a New South Wales coastal town. Ruth’s life is punctuated by an occasional phone call from her two sons, the activities of two companionable cats and the humdrum tasks of eating, taking her medication and counting the pattern of the waves. Scarcely able to take care of herself, Ruth eats sunflower seeds for breakfast and struggles with a bad back that escalates as the story progresses. She cuts a lonely yet content figure.

Early on in the story, readers are introduced to the presence of an intrusive tiger that prowls Ruth’s house by night with a ‘vibrancy of breath that suggested enormity and intent’. Whether the tiger is a manifestation of Ruth’s failing mental health or an element of magical realism akin to a concretised premonition that precedes the arrival of a far more disturbing threat, is open to readers’ interpretation. Arriving unannounced at Ruth’s doorstep a day after her strange encounter with the feline beast, a ‘large as life’ government carer by the name of Frida assures Ruth that she’s not a stranger nor a friend – just a carer dispatched to take care of Ruth and clean the house for an hour a day.

Kind and acquiescing at first, Frida is a fascinating creation who defies the traditional characteristics of an antagonist as she oscillates between thinly masked manipulation and surprising bursts of tenderness. As Frida gradually worms her way into each and every space of the house with her constantly changing hair, bright disposition and determined efficiency, she takes over Ruth’s life to such an extent the widow forgoes her independence, becoming a captive in her own house – much like the fabled tiger she imagines every night.

McFarlane draws on the harsh natural environment, taps into the isolation of old age and the vulnerability of a lonely person forging new social relations to foster a steadily escalating sense of foreboding. The presence of the tiger, together with Frida’s exotic appearance which Ruth mistakes for Fijian, conjures up Ruth’s extraordinary childhood. Ruth revisits her days as a child of missionary doctors in colonial Fiji and narrates tales of her yesteryear to someone who is finally there to listen.

We learn that as a teenager, Ruth fell in love with a doctor by the name of Richard Porter whom she subsequently regains contact with and invites over to her beach house. The tale meanders into a compassionate meditation on the possibility of love in one’s old age, culminating in a touching scene that takes place in Ruth’s bedroom. McFarlane expertly captures the need for people to be memorialised in the recollections of others, as deftly as she delves into Ruth’s consternation at being patronised by her children. Ruth concedes that ‘she was neither helpless nor especially brave; she was somewhere in between, but she was still self-governing.’

In addition to Ruth’s heightened recollections of Fiji and profound observations, we learn that she is an unreliable narrator whose perception of the present isn’t as clear as it might be. Richard’s departure, together with a clear shift in Frida’s behaviour, coincides with Ruth’s increasingly deteriorating health and disorientation. Ruth’s receding lucidity becomes enmeshed with dream-like sequences as she falls under Frida’s control, in turn forcing readers to question which events do and don’t take place. Bursts of clarity shine through Ruth’s failing memory, however, as she comprehends that something sinister is afoot.

McFarlane is an expert at dropping vital bits of information at exactly the right moment, cultivating an acute sense of suspense and the subsequent realisation of what exactly has come to pass. With beautiful prose and unexpected moments of humour and gentleness, The Night Guest is a pulsating psychological thriller that offers us but a glimpse into the recesses of a diminishing mind and the scarcely concealed depravity that resides in many people.

The Night Guest has been shortlisted for the Stella Prize 2014. The prize will be announced on the evening of Tuesday 29 April.

Rating: 4 ½ out of 5 stars

The Night Guest

By Fiona McFarlane

Softcover

276 pages

ISBN: 9718926428550

Penguin Group Australia