A lot’s already been written about the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Communications and the Arts’ Report on the 2020 Parliamentary Inquiry into Australia’s creative and cultural industries and institutions. Many peak bodies immediately welcomed the report, and I’ve taken a look at how its recommendations compare to those of the 2015 Senate Inquiry on the Impact of the 2014 and 2015 Commonwealth Budget decisions on the Arts, as well as sounding caution on the role of the Productivity Commission.

While there’s plenty to celebrate, the report raises concerns that the sector continues to work through, as was discussed in detail at Reset last week.

Here are three of those concerns:

1. It seeks to improve the Commonwealth’s understanding of the arts…

As artists and peak bodies tried their best to engage political decision-makers throughout the pandemic, it became increasingly clear that there was no common understanding of Australia’s arts and cultural sector: how artists earn their incomes; how national touring works; the sector’s size and diversity.

It’s welcome to see the report detail how the ABS currently gathers and presents arts and cultural data – data on employment patterns, working hours, government and non-government expenditure etc – and what use is made of this work.

There are useful recommendations on adding questions to the Census to capture multiple professional activities, enhancing the scope and frequency of the Cultural and Creative Satellite Accounts, and making sure that precarious work (whether paid or unpaid) is captured.

…but it offloads all responsibility to local government and the states.

The report’s first recommendation – ‘a national cultural plan to assess the medium and long term needs of the sector’ – segues immediately to the second recommendation – ‘that the Commonwealth Government encourage each level of government to develop and administer strategies to grow cultural and creative industries within their own jurisdictions.’

Let’s take a closer look at that.

The Commonwealth is not expressing a commitment to a ‘national cultural’ policy, but instead, an interest in a plan to ‘asses the medium and long term needs’, which it then expects to see addressed by local and state governments ‘within their own jurisdictions’.

This report makes no recommendations that the Commonwealth Government develop any kind of strategic approach to the arts and cultural sector. No policy, no strategy, no plan.

On top of that, the report recommends that the Productivity Commission ‘inquire into the legislative arrangements which govern funding of artistic programs and activities at all levels of government,’ with a consideration of ‘barriers and opportunities’ for their establishment.

Read: Resetting our arts boards

Local and state governments across Australia already have policies, strategies and plans with a focus on arts and culture, creative industries, regional creative place-making, community development, disaster recovery and so on. They’re already leading the way. While the report repeatedly quotes artists and organisations championing the specific role the Commonwealth needs to play, there are no recommendations addressing this.

While the Inquiry’s terms of reference had included identifying ‘the best mechanism for ensuring cooperation and delivery of policy between layers of government’, this is not covered by the report. There is no recommendation to reinstate the biannual Meeting of Cultural Ministers or to replace it with a similar mechanism which ensures that all three levels of government meet with purposeful intent on a regular basis.

2. It calls for specialist professional development programs…

With the voices of artists presented prominently across the report, there’s a good deal of focus on what’s needed to sustain a professional career, as well as on the role of arts education for everyone.

There’s quite a list of recommendations on specific programs that could emerge to support artists across various career stages. These include ‘pilot program’ internships and cadetships, and an ‘Art Starter portal’ website with information such as financial and digital literacy, intellectual property, and business monetisation mentorship.

… but it marginalises tertiary education.

A career as an artist or artsworker is founded on years of focused, expert education and training.

In no other professional field would we see education, training and professional practice reduced to a website, as though a portal could redress issues currently occupying many hundreds of specialist art schools, university departments and peak bodies spanning all practice modes.

We’ve long come to recognise how standalone programs can vanish as quickly as they were created, such as JUMP and the other ArtStart.

Tertiary education nurtures rigorously researched, long-term approaches to arts and culture. While the report recommends that ‘the Commonwealth Government consider working with tertiary education providers’ to provide internships and cadetships in regional locations, the gutting of universities and TAFEs throughout and well before the pandemic adds insult to injury. With more and more regional campuses no longer viable, it’s difficult to imagine how this recommendation could be delivered.

And while the report commends the Victorian Government Creative Workers in Schools program delivered by Regional Arts Victoria, it stops short of articulating this as a recommendation for national delivery.

3. It recommends reinstating ‘arts’ into the Department’s name…

The invisibility of the arts to the national agenda was personified in the sacking of Mike Mrdak AO, the highly accomplished former Secretary of the Department of Communications and the Arts, and then the removal of ‘arts’ from the name of the government department.

The report recommends putting it back in: that ‘the title of the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications be amended to include the Arts.’

More than just a word has been lost, however, and more than just a cosmetic response will be needed.

… but it diminishes the Australia Council.

The Australia Council is near invisible in the Parliamentary Inquiry Report on Australia’s creative and cultural industries and institutions.

Despite large-scale hits on its strategic plans and budgets across the past six years, significantly reducing its capacity to achieve its mission, there is no recommendation that the Australia Council’s operating budget be increased substantially.

Despite evidence on the Australia Council’s national and industry value presented by artists and organisations all across the report, there is no recommendation that the Australia Council’s arm’s-length, non-partisan peer assessment model be strengthened.

Read: Resetting our arts boards

And despite having repurposed its own internal funds to provide urgent pandemic support while the Office for the Arts was granted significant funds to deliver RISE, there is no recommendation that the Australia Council’s budget be set and maintained at levels that allow their strategic plans to be implemented in full.

One recommendation for a new program – ‘Local Artistic Champions’ – proposes a new fund delivered by ‘the Office for the Arts, in collaboration with the Australia Council’, for creative professional development. This introductory approach significantly diminishes the expertise of the Australia Council, who have offered far more sophisticated professional development programs and funds for decades. An additional program delivered at electorate level would be a welcome way to engage local MPs in understanding how artists in their communities work. It would be important, however, to ensure that such a program did not fall victim to the ‘sports rorts’ politicisation we’ve seen of government programs delivered outside of expert, arm’s-length bodies.

The Australia Council is ‘the Australian Government’s principal arts investment, development and advisory body.’ Just a few years ago, this statement read ‘arts funding and advisory body.’ No need for the qualifying ‘principal’, as though the Australian Government has other arts funding and advisory bodies who might displace the Australia Council. Since 1973 it has developed expert strategies that reflect a thorough understanding of arts and cultural sector needs, programs of varying scale, from individual early-career artists to established practitioners, from edgiest arts organisations to sector development bodies.

The report on p.127 sets out one element of the Australia Council’s strategic approach: a comprehensive policy and program spanning First Nations self-determination, creative and cultural production, tourism, export, mental health and more. Nowhere in the report is the Australia Council’s work unpacked or engaged with in addressing the issues raised by multiple respondents, despite this being the Council’s purpose.

As we’ve seen, the report’s first recommendation is for ‘a plan to assess the medium and long term needs of the sector.’ This is what the Australia Council does every day.

The deliberate, systematic undermining of the Australia Council each year since its Culturally Ambitious Nation strategy was thwarted and the National Cultural Policy jettisoned, reaches a new culmination in this report.

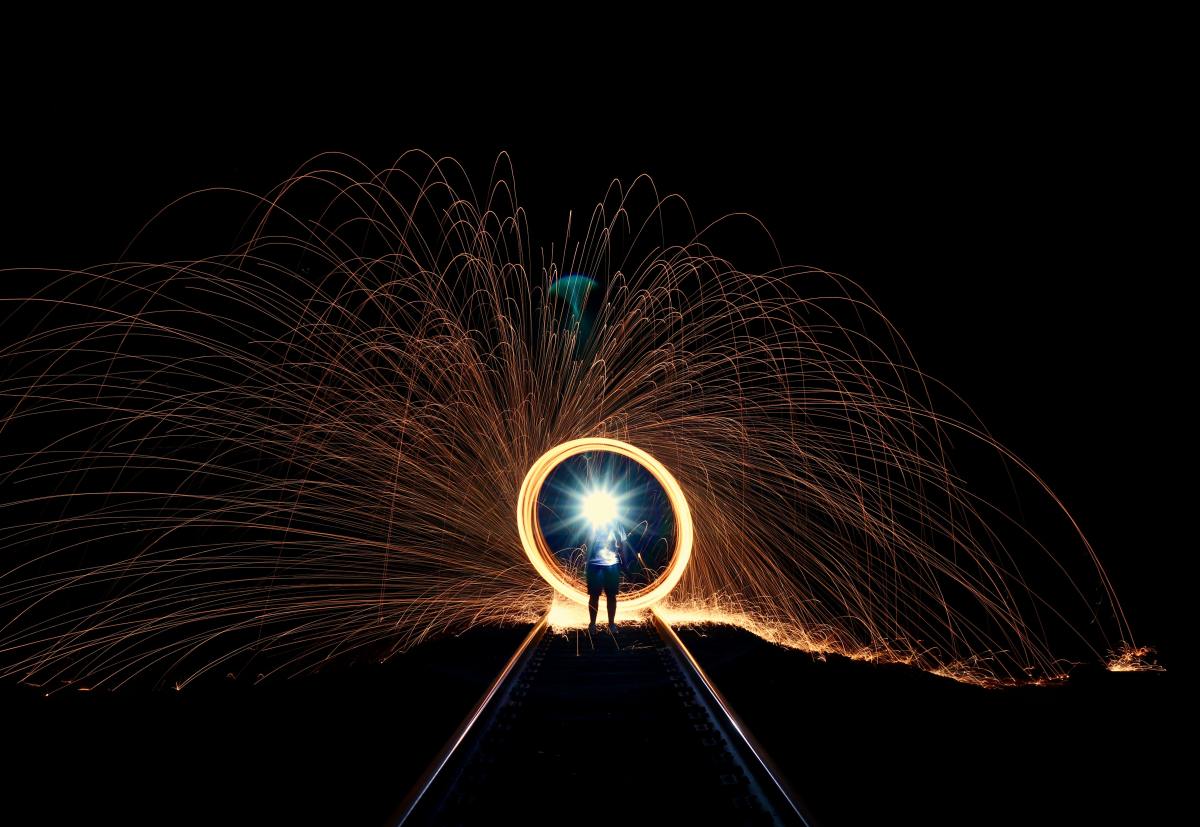

The report’s full title – ‘Sculpting a National Cultural Plan: Igniting a post-COVID economy for the arts’ – gives pause for thought.

Sculpture gives new form, new strength and focus. It makes the very best use of materials to hand – but it does so in ways that will stand the test of time.

The creative economy doesn’t need mere ignition – we’re no flash in the pan; we’re a slow burn. We’re the fire in the belly and the light in the soul.

Arts and culture don’t need quick fixes. We need meaningful policies with sustained, strategic impact. This is the opportunity that awaits Australia’s next government.

Reset: A New Public Agenda for the Arts ran over 11-12 November 2021.