Amongst other many disturbing issues raised in the Australian Law Reform Commission’s Copyright paper is a proposition to send us down a path of a US style ‘fair use’. So, to get some handle on how fair use works in the US, I had another look at the US Prince v Cariou decision, a recent ruling on a copyright suit involving photographer Patrick Cariou and appropriation artist Richard Prince.

As an independent creative who survives on producing interesting visual content, the outcome of this so far is pretty scary and it’s probably not over yet!

The 30 plus years’ experience I have with the profession of photography points to a vast investment of passion, time, money and skill into story-telling with the pictures I shoot and at the same time documenting aspects of society and culture that are of great personal interest.

Although I’ve never met Patrick Cariou, he’s obviously one of these passionate artists. He produced a photographic book about Rastafarian culture after spending six years living and working with a community in Jamaica. The book reportedly made about $8,000 in sales and Cariou has apparently never commercially licensed individual photographs. Here’s a true artist with great passion and commitment. All society benefits from books and collections like Yes Rasta, even if they’re not top-sellers.

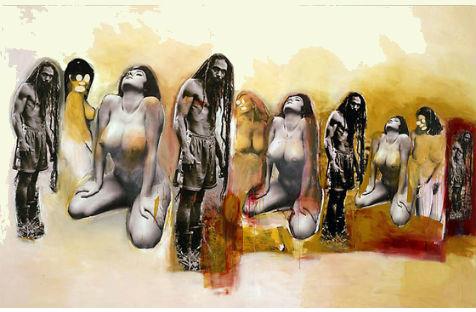

Perhaps the beauty of Cariou’s images struck appropriation artist Richard Prince. He painted shapes, gas masks and guitars on thirty of the photographs. What he didn’t do was ask Patrick Cariou for permission to do that. Prince’s Canal Zone series was exhibited at the Gagosian Gallery and published in its catalogue (by Rizzoli books). The show is said to have generated more than US$10 million in sales. When I look at what was done to his photographs, I’m not surprised that Cariou was pretty annoyed.

Cariou sued Prince, the Gagosian Gallery and Rizzoli books for copyright infringement. Initially, (as one would expect) Cariou won. But then last month, the Second Circuit reversed the decision in Prince v Carioiu.

Under the so-called ‘fair’ use doctrine in the US, Prince’s appropriation of twenty-five of Cariou’s photographs was considered “transformative” and so not an infringement. What happens with the other five images highlights the whole issue of uncertainty in relation to courts and lawyers working these things out.

The most bizarre aspect for me in all of this was the court’s comments to the effect that they were in a position to make artistic judgments about the quality of photography and art. I’m a bit surprised to learn that under the US fair use system, the photographer’s intention for the work didn’t seem to count for anything. Also, the fact that the photographs at issue weren’t generated for commercial purposes, as Prince’s work is, seemed to mean that the original painstaking, time consuming, passionate images weren’t valued by the court.

I never thought that the worth of art or photography should be determined by its commerciality and yet this is what the court seems to be saying – when you read through the decision.

Unfortunately, reworking of Copyright legislation is not on the same scale of interest for the sensational shock jock issues that fill our media every day around the forthcoming federal election, but the ALRC’s discussion paper about copyright and the digital economy seems to suggest how great it would be if Australia adopted a fair use system similar to that in the US. All I can say is that I hope the ALRC plays fair, turns the volume down on the multi-national corporate entities, lawyers, academics and media organisations and listens a little more carefully to small-time and emerging creators who rely on copyright as one of the ever-diminishing ways to make a living.

Chris Shain is writing a response to the ALRC discussion paper on behalf of the Australian Institute of Professional Photography (AIPP).