In April 1770, British naval officer Lieutenant James Cook (later Captain Cook) sailed along the southeastern coast of Australia. Declaring the landmass terra nullius, he planting a flag for the Empire. It was in direct contradiction to a journal entry Cook had made days earlier, observing from afar that his ship was ‘so near the Shore as to distinguish several people upon the Sea beach they appear’d to be of a very dark or black Colour but whether this was the real colour of their skins or the C[l]othes they might have on I know not.’

Six days after that comment, Cook made landfall. This year we face the 250th anniversary of that journey – and Australia is still coming to terms with what followed.

While anniversaries are usually moments for celebration, this one is tinged with great complexity and contradictions. We asked five curators across the gallery and museum sector, each of whom have created exhibitions that attempt to unpick the layered histories around the Cook narrative, to offer a contemporary consideration for moving forward.

Shannon Brett (Wakka Wakka, Butchulla and Gurang Gurang peoples)

Rite of Passage, QUT Art Museum, Brisbane, 7 March – 10 May

‘First and foremost, it’s important for me to address this as an Aboriginal person, and secondly a curator. This exhibition I’ve curated is about many things. It’s about historic inaccuracies delivered to the general population regarding James Cook and it’s also a response to the “celebrations” surrounding this anniversary. It’s about the assault upon people’s rites of passage and our rights moving forward.

‘As a curator I wanted to balance out the conversation regarding this particular year. It’s not a celebration for everyone. These artists are very specific in the way that they practice their Aboriginality and I admire what they have proclaimed for this exhibition.’

Jenna Lee, un /bound passage (detail) 2019. hand-dyed and folded paper installation from pages of ‘The Voyages of Captain Cook’ Ladybird Book, with video projection. Courtesy of the artist.

Jenna Lee, un /bound passage (detail) 2019. hand-dyed and folded paper installation from pages of ‘The Voyages of Captain Cook’ Ladybird Book, with video projection. Courtesy of the artist.

For Rite of Passage, 11 contemporary artists define their quest to preserve their Aboriginality: Glennys Briggs, Megan Cope, Nici Cumpston, Karla Dickens, Lola Greeno, Julie Gough, Leah King-Smith, Jenna Lee, Carol McGregor, Mandy Quadrio, and Judy Watson.

‘It’s about sharing the whole truth with each person in our country and it’s about celebrating and respecting Aboriginal people as the sovereign people of this land.’

The overriding message Brett wanted to communicate is, ‘Culture exists’. She continued: ‘Unfortunately, this country holds a largely untold history. Artists have the power to re-establish facts that may have been lost (or hidden), and to bring important issues into the consideration of our everyday conversations, which fundamentally educates each developing generation.’

In response to the current zeitgeist to visit alternative perspectives around the Cook anniversary, Brett told ArtsHub: ‘They’re not fresh perspectives to me. Perhaps they appear fresh because we’ve been silenced for so long?

‘I don’t believe that sovereign perspectives should be categorised as new points of view, especially when those perspectives are about our own country. The reality is that our country/planet is evolving, and we need to work together to save it … I am grateful that I can take part in the conversation.’

Travelling Bungaree, featuring project artists L-R: Bjorn Stewart, Warwick Keen, Blak Douglas (aka Adam Hill), Jason Wing, Amala Groom, Karla Dickens, Leanne Tobin, Caroline Oakley, Djon Mundine, 2015. Courtesy Mosman Art Gallery.

Travelling Bungaree, featuring project artists L-R: Bjorn Stewart, Warwick Keen, Blak Douglas (aka Adam Hill), Jason Wing, Amala Groom, Karla Dickens, Leanne Tobin, Caroline Oakley, Djon Mundine, 2015. Courtesy Mosman Art Gallery.

Djon Mundine OAM (Bandjalung people)

Bungaree’s Farm, Mosman Art Gallery, 28 March – 17 May

Megan Cope: Black Napoleon, Mosman Art Gallery, NSW, 28 March – 17 May

Djon Mundine says it simply: ‘For Aboriginal people, the coming of Cook was not a positive event – it has resulted in death, displacement and destruction of our societies.’

Mundine describes his exhibition Bungaree’s Farm, shown alongside The Black Napoleon by Megan Cope, as ‘dialectic devices to discuss the coming of the British Imperial power represented by James Cook … and the results of colonisation. The British view of Cook’s voyage is well documented and published. Aboriginal people’s thoughts and reactions were, until recent times, rarely taken into account, let alone recorded, and not discussed publicly by current Australian national society. These art pieces are the view of the “other”, in the “first voice” of the other.’

For Mundine the overriding message by telling the story of Bungaree is to bring the audience in contact with a living personality – ‘a real human being, not just a cypher.’

Bungaree’s Farm is an exhibition of contemporary Aboriginal audio, video, performance and installation art exploring Bungaree’s legacy. Bungaree, known as the Chief of the Broken Bay Aborigines, was a central figure in early Colonial Sydney, and the first person known to have been called an ‘Australian’.

Bungaree’s Farm was commissioned in 2015 to mark the 200th anniversary of the establishment of Bungaree’s Farm by Governor Macquarie and this exhibition is the result of a series of intensive residency workshops led by Mundine, and originally showcased in the T5 Camouflage Fuel Tank on the site of Bungaree’s Farm. Participating artists are Daniel Boyd, Blak Douglas, Karla Dickens, Leah Flanagan, Amala Groom, Warwick Keen, Peter McKenzie, Djon Mundine, Caroline Oakley, Bjorn Stewart, Leanne Tobin, Jason Wing, Chantal Woods and Sandy Woods.

‘We don’t re-write history, we bring the true history into the light.’

Mundine continued: ‘I have attempted in nearly all the exhibitions I’ve curated, to three-dimensionalise Aboriginal artists, societies and people – to keep reminding Australian society that we are intelligent adult human beings. We know many aspects of Cook’s personality (and his crew). In the 250 years since, Aboriginal people weren’t really seen as intelligent human beings, but as sub-human.’

Mundine believes art succeeds where words fail. ‘Colonial British invaders struggled with language translations and still do, so we use art, imagery and objects to hopefully better communicate. To deny our Aboriginal story, history and crimes against us cannot be allowed. We exist now because our ancestors were murdered then. These colonial crimes must be acknowledged and forms of restitution of our societal position and reconciliation made. We don’t re-write history, we bring the true history into the light. This we know, and attempt to never forget, and keep telling these stories in our art.’

He added that in many ways Australia is still stuck in the colonial experience.

‘Australia as a nation couldn’t really talk of post-colonialism as we were still a colony, and thought of as such. However, a significant shift in Aboriginal consciousness, within ourselves has been active across the arts and all cultural forms and ensures we remain at the existential focal point,’ said Mundine.

These are ideas that Quandamooka artist Megan Cope has recently explored through an Australian Print Workshop residency in 2017 to the United Kingdom and France to explore the archives and collections of early French exploration of Australia and the Pacific.

The resulting suite of new works was created in response to the people who defied the expanding Empire, in particular the story of ‘The Black Napoleon’, the title of which Cope adopts for a solo exhibition shown alongside Bungaree’s Farm and continuing the colonial conversation in the year of Cook at Mosman Art Gallery.

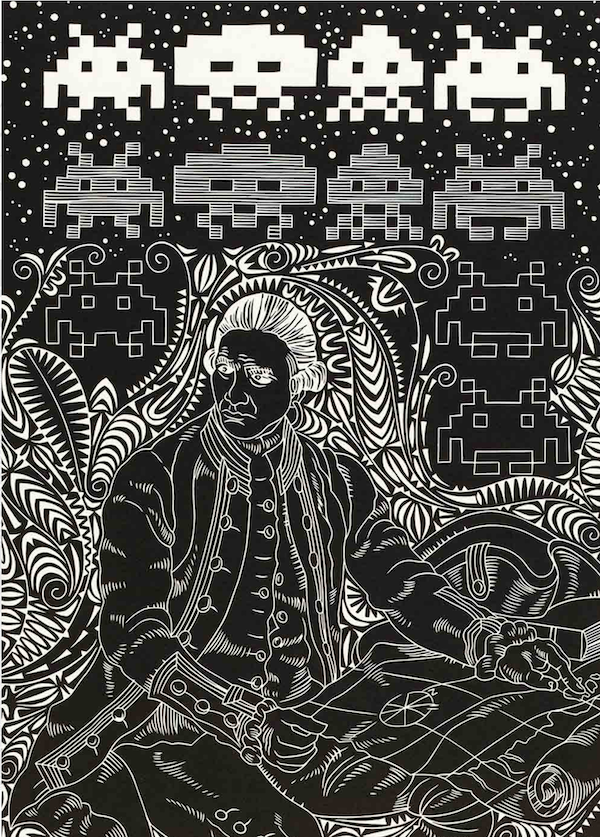

By virtue of this act I hereby take possession of this land by Brian Robinson. Courtesy of the artist and Mossenson Galleries.

Dr Ian Coates

Endeavour Voyage: The Untold Stories of Cook and the First Australians, National Museum of Australia, Canberra, 8 April – 11 October

Endeavour Voyage was a curatorial team exercise headed up by Ian Coates, National Museum of Australia’s senior curator. He said this was important because, ‘at past anniversaries the 1770 story has been dominated by accounts of Cook as a peerless seaman, a leader whose voyage transformed European knowledge of the world.

‘Another crucial part of this story is the perspective of the nation’s First Australians, whose history stretches back more than 65,000 years. Until now their voices have been missing from the Cook story. In bringing these two parts of the story together, Endeavour Voyages offers an opportunity for visitors to embrace the shared history of this land.’

Coates believes this is an important ‘opportunity for Australians to reflect anew on the history that began to unfold on the shores of this continent 250 years ago. There is an opportunity to learn about this story from all perspectives and think about what it means to live in this country today. In looking at our past in this way, we have the chance to come together, to learn and share stories and views of our history, and to imagine a shared future.’

He continued: ‘As well as featuring the voyage of the Endeavour up the east coast of Australia, the Endeavour Voyage exhibition examines the changes in the way Australians have marked this event over the years. In 2020, it is clear that many Australians are seeking to understand what the Indigenous perspectives on the Cook-Endeavour story are. We have worked across seven locations along the east coast with descendants of those people who witnessed the passage of the Endeavour through their country. These local perspectives offer new insights into this complex story.’

Coates explained: ‘In this exhibition we bring together a diverse range of art and objects, including: the botanical and zoological illustrations of Sydney Parkinson and Herman Sporing; Nathaniel Dance’s iconic portrait of James Cook; some contemporary works by Indigenous community artists done at Yarrabah, Wujal Wujal and Hopevale; others by contemporary Indigenous artists such as Michael Cook, Brian Robinson, Jason Wing and Vincent Namatjira. All of these – in different ways – offer new insights into the complex story of what happened in 1770 and its impact on our lives today.’

Timothy Cook, Kulama 2009. Collection Art Gallery of New South Wales. © Timothy Cook. Photo: AGNSW, Diana Panuccio.

Cara Pinchbeck (Kamilaroi people) and Jackie Dunn

Under the stars, Art Gallery of New South Wales, 21 March – 20 September

Co-curators of the exhibition Under the Stars, Cara Pinchbeck, senior curator Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art and Jackie Dunn, special exhibitions curator at AGNSW, turn to navigation and a unifying sky to rethink the Cook narrative.

‘Under the stars is an opportunity to tell some of the many stories and perspectives of people’s relationship with the night sky, and to explore – at a time when discussions of Cook will be dominated by questions of ownership – a territory that is not owned, but rather that connects us all,’ they explained.

‘The night sky was important to Cook, who used knowledge of the stars to navigate. They were also at the heart of one of the key objectives of his journey: to observe the rare transit of Venus in 1769. By bringing together diverse artworks that look to the skies to map the planets and stars, we wanted to curate an exhibition that marks the 250 year anniversary of Cook’s landing at Kamay (Botany Bay), but it is not an exhibition with Cook at its centre – it is positive, optimistic and inclusive.

‘By taking a transhistorical, cross-cultural approach, Under the stars presents Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists, highlighting the commonalities and connections in our shared attempts to understand the night sky and our place in relation to it,’ Pinchbeck and Dunn added.

‘We hope these connections in turn reveal the long history of Australia’s First Peoples’ engagement with the outside world and the deep sky knowledge that informs cultures, going back centuries if not millennia … Ultimately, we’re looking at a shared sense of living in the world.’

The curators felt it was important to revisit, contest and rewrite histories through art, ‘in part because the dominant western models have held the stage for the past 250 years.

‘Here we’ve taken the opportunity to engage across disciplines, cultures, time and space in the exploration of a politically potent yet poetic, universal yet topical, theme. But we’re also deliberately celebrating Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives and knowledge systems (ones not recognised by Cook) to reset our thinking,’ Dunn and Pinchbeck concluded.