Following the deaths of Barry Humphries and Rolf Harris earlier this year, a perennial question has reared its head once again: how should we deal with the art and artistic legacies of artists who have caused harm? This question pokes uncomfortably at a fundamental aspect of art: the “holy trinity” relationship that exists between the artist, the art and the audience.

While art, artist and audience are all separate entities, knowing where one ends and the other begins can be a difficult line to draw. Is it solely the genius artist that is responsible for “perfect” art? Is genius art simply determined by the audience? Or is the genius of the art independent of both the artist and the audience?

This trinity makes it very personal when the moral standing of the artist and/or the art is called into question.

When speaking with a select group of Australian contemporary artists, their response to the question of whether we can separate the artist from their art was a unanimous “no”.

They all agreed, at least on a fundamental level, that you cannot separate the artist from their art. Delving deeper into questions challenging this fundamental belief, however, it becomes clear that there are many complexities surrounding this it.

Claire Dederer, author of Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma, notes that the question of separating the art from the artist appears to only arise when the artist and their art is deemed to be a genius.

A perfect example of the kind of response that those who aren’t deemed to be genius receive, is how the public dealt with Rolf Harris following his conviction in 2014, and the response to his death this year.

Many were more than happy to discard his paintings and even erase murals following his conviction. The majority appeared to have no qualms in immediately removing both the art and artistic legacy of the celebrity-artist.

This seems to suggest that the aforementioned holy trinity only applies to art that is regarded as genius, or that the relationship is far weaker when dealing with less than genius artists. For instance, would anyone ever be so full of righteous conviction as to actually destroy a Picasso?

The very concept of a genius drives the question of “can we separate the artist from the art?” Without it, more often than not, people don’t care enough to even ask the question.

Speaking with ArtsHub, performance artist Harriet Gillies asserts that we are all geniuses, and to believe otherwise would be a stretch of the imagination.

‘I think people are geniuses when they find their car keys,’ says Gillies. ‘This idea that there are people who are innately more gifted or creative than other people, I think that’s a bit of a far-fetched idea. But we live in celebrity culture and celebrities have taken over the role of saints and gods, and humans will always want to worship something.

‘[It is also] one of the best experiences you can have in art, when you’re there with a large group of people, just feeling so much smaller than this thing that’s bigger than any of you… Humans are just so silly and flawed. Even in how we choose to worship one another, funnily enough.’

When artists are placed on a pedestal of genius proportions, it seems inevitable that they may fly too close to the sun at some point.

Multidisciplinary artist Abdul Abdullah suggests that when we are asked to confront the human messiness of our genius artists we often struggle, because we are also being asked to confront our own flawed nature.

‘People stake themselves in a cultural moment like that, or a person like that, [so when they are called into question], then they don’t want to reflect on themselves,’ says Abdullah.

Audiences can identify with the artist and the art to such an extent that their sense of self merges with them. This is the power of the holy trinity that characterises genius art. It blurs the boundaries between the audience, the art and the artist.

This makes it difficult when the artist or the art are called into question. As it forces us to reflect and possibly re-evaluate on our personal values and beliefs.

Abdullah’s work is known for asking provocative and uncomfortable questions, which often urge his audience to reflect on what they think they know, or believe in.

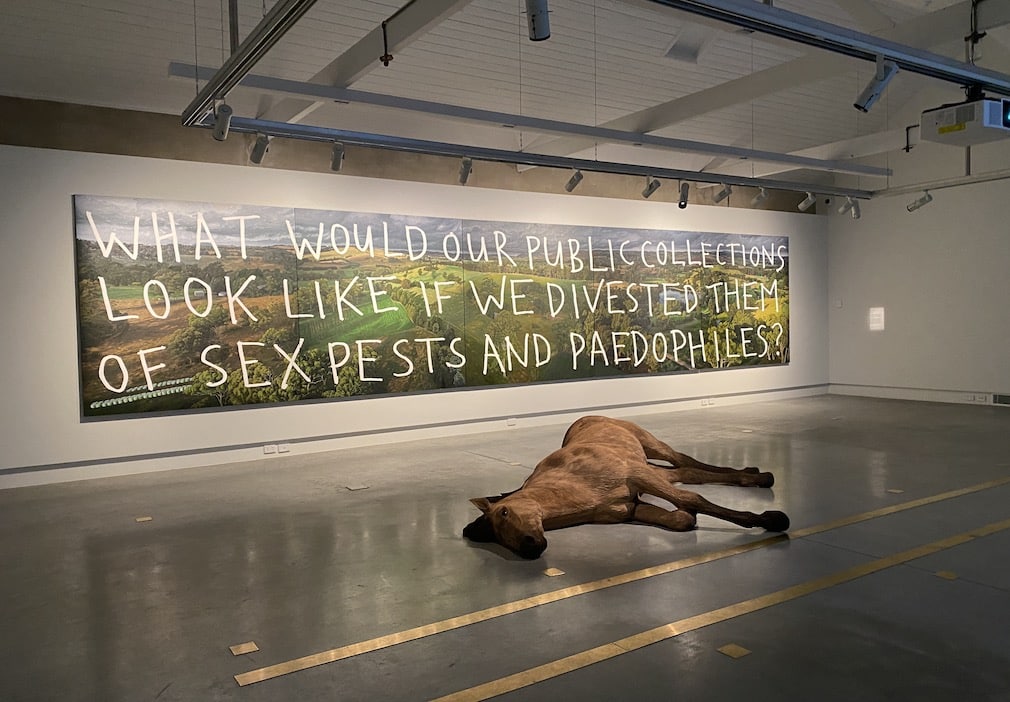

In a recent exhibition at the regional art gallery Ngununggula, titled Land Abounds, a painting of Abdullah’s hung on the wall depicting a typical “Australian” landscape – something we’re used to seeing in our public collections.

Written across it, however, in upper case white letters was the question: ‘what would our public collections look like if we divested them of sex pests and paedophiles?’

Abdullah shares with ArtsHub some of the more interesting responses to his painting, Legacy Assets.

‘The negative response that comes is that immediate, defensive posture of, “you’re telling me what I can and cannot like”, which is interesting and I think revelatory, because the work in my opinion doesn’t [do that]… I’m actually just saying “what would our collections look like without these particular artists?” It’s more of an interesting conundrum.’

Abdullah’s artistic practice, and the strong responses it often provokes, demonstrates that there is value in being able to confront difficult questions, to interrogate the uncomfortable complexities, without first presuming to have all the answers.

Outside of artistic provocations, however, decisions need to be made. So how do we find the right answers? As visual artist Alan Jones tells ArtsHub, creating blanket rules for questions as ethically complex as these isn’t possible, or desirable.

‘You know, like Margaret Court for example, the tennis player, there’s been debate about whether we take her name off the Margaret Court Arena in Melbourne. I’ve actually been a supporter of that, because she’s so open about her views on homosexuality and the LGBTQIA+ community, which essentially don’t fit into today’s society,’ Jones says.

‘But do I think we should be going through the art gallery saying, “oh, you know, we found out that this person here did something, let’s take their picture off the wall?” Maybe not?’

The complexities of these debates warrant the perennial nature of these questions. It is also why each of us should be wary of creating homogenous responses to similar cases where artists have perpetrated harm.

After the death of Barry Humphries, a spotlight was returned not only to his transphobic comments, but also to his public support of Donald Friend. Humphries had once described Friend, in a foreword to Friend’s published personal diaries, as demonstrating a ‘benevolent form of pedophilia’.

Abdullah tells ArtsHub that he’d be surprised if those who continue to defend the public display of Donald Friend’s paintings do not have financial stakes in the continued display of his artworks.

‘Art is inextricable from the artist when it comes to assigning financial or cultural value,’ says Abdulllah. ‘but [is often] conveniently siloed when it comes to personal bad behaviour.’

Jones, however, wonders whether the bad behaviour results in the artist “cancelling” themselves.

‘You’re not taking in the art anymore. All it is, is just a reminder of the crime, or the personality, or the artist you know, and so maybe in a way, the work cancels itself,’ he says.

When considering her own experiences of engaging with art while having harmful information about its maker, Gillies tells ArtsHub that she believes there is a place beyond cancelling.

‘I think that for all intents and purposes, all of that information becomes a part of the dialogue. But where I think it isn’t useful is when people use that information to cut the dialogue off.

‘I think there’s a more interesting place where we can have this harmful information and keep the dialogue going, and push through this really difficult phase – and it’s really like this phase that has a lot of shame and a lot of confronting feelings – and continue the dialogue [anyway].’

There is an alchemical quality that characterises genius art. The trinity that exists between the artist, the art and the audience creates fertile ground from which transcendental experiences can flourish. These are the kinds of subjective experiences that distinguish the art we hold as genius, from the art that we do not.

Gillies describes the transcendental experience of genius art as: ‘lots of things happen[ing] at the same time’. One of these key things is the aesthetic choices made by the artist. However, ‘there are other things that need to coalesce in the right way at the right time,’ she says.

What makes a work of art feel perfect, genius or transcendental, goes beyond the choices made by an artist, but also not in spite of them. Just as you cannot separate the artist from their art, you cannot solely attribute the genius of the art to the aesthetic choices made by the artist.

The genius is in the alchemy that occurs between the artist, the art and the audience, in light of the cultural time and place that they are inhabiting.

What is interesting about these perennial questions is that they are asking us to consider deeper ones. Like what makes great art? Why do we choose to call certain artists geniuses? What does genius mean? And, most strikingly, they ask us to confront our own human messiness.

When our geniuses behave badly we should see this as an opportunity to interrogate the uncomfortable complexities of being human, instead of shutting down dialogue, or following unexamined blanket rules. In doing so, we can hopefully arrive at a more interesting place.