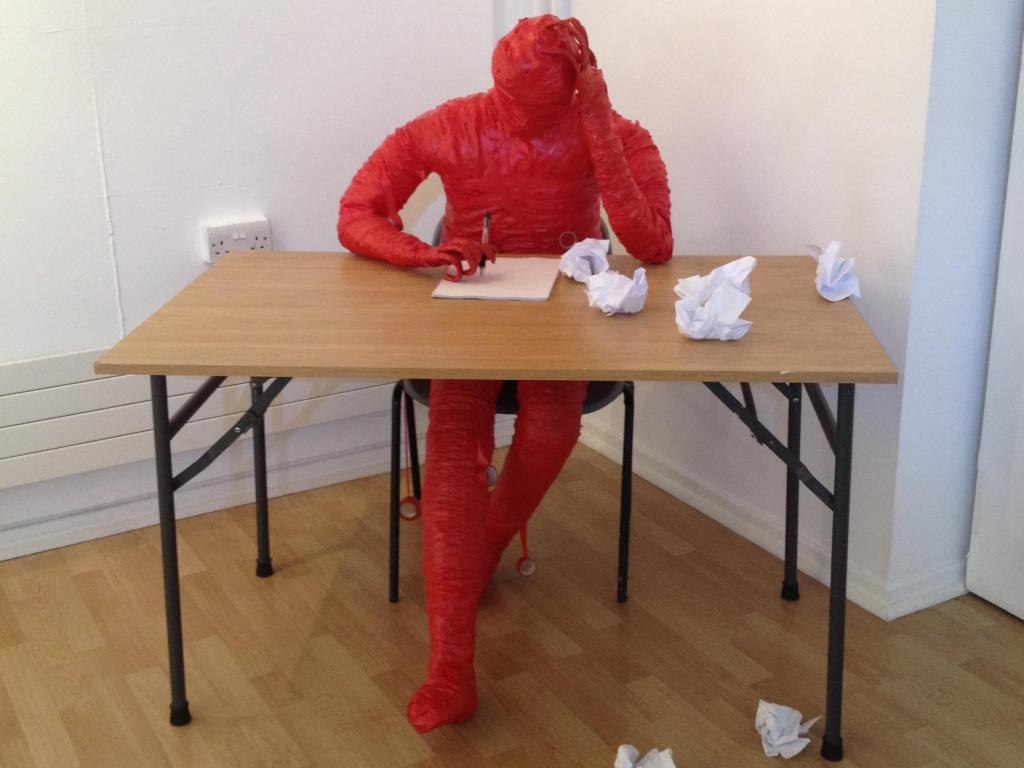

Deirdre Bennett, Red Tape (2014). Image source: www.deirdrebennettart.wordpress.com

Arts organisations have important services to deliver. At times, however, the single and combined pressures of federal, state, local and private bureaucratic processes that are supposedly enabling organisations work in reverse to stymie and fatigue them.

When new Australia Council CEO Tony Grybowski took the reins in May last year, ArtsHub reported that he promised a new streamlined system designed to make funding application easier.

In August, the unveiling of the Australia Council’s new grants program revealed that 150 grants had been reduced down to five categories. Until changes are implemented in January 2015, it remains unclear whether this mode of streamlining at the federal level will be favourable for arts organisations. On close inspection of the new Strategic Plan, ArtsHub found the lack of detail to be extremely concerning.

Sheila Hollingworth, Manager of Creative Clunes and Clunes Booktown, agrees that some form of streamlining is overdue.

‘If there was a way for some of the processes to be streamlined so it wasn’t a constant reworking of essentially the same sort of material, then I think most organisations would be happy to spend less of their time on that and more on delivery,’ Hollingworth said.

With applications going out to the Australia Council, Arts Victoria, the Copperart Agency, as well as state government departments including the Department of Regional Development, federal bodies such as the Anzac Centenary, AsiaLink and the Australia Korea foundation, Creative Clunes are experts in the art of bureaucracy.

‘We appreciate the importance of the process of applying for money, and being accountable for how it’s spent to government, or whoever the funding body is, as well as the community more broadly. But at times it can be a long and cumbersome process and it certainly takes up a lot of time,’ Hollingworth said. She estimates that over the course of a year, the equivalent of a number of weeks is spent on funding applications alone.

‘Each grant requires a slightly different presentation on often the same material,’ Hollingworth explained.

‘Sometimes the forms you have to complete have been set up in a cumbersome electronic format, like you have to go into a form that’s been designed by organisations but then it’s not very user-friendly when you’re entering data and so you’re cutting and pasting over and over and trying to make things look presentable.

‘So there are basic things like that – as well as the fact that you have to keep re-describing your organisation, your goals, your mission – but often in slightly different ways. It’s a very lengthy process when you’re applying for different grants in different ways.’

‘The amount of reporting that actually has to happen is just bizarre,’ says arts accountant, Brian Tucker.

‘For arts organizations that are funded through the Ministry of the Arts, they have to prepare separate audits and financial acquittal for each and every grant that they get, even though by inference you can draw that from the audited financial statements. I know that government has to maintain oversight how government funding is spent. But it does seem to me that there are duplicated and triplicated layers of financial reporting and the information is actually there,’ Tucker said.

Tucker recalls when he was Treasurer of the Institute of Modern Art 20 years ago, the Artistic Director commented that ‘we spend as much time acquitting grants as we do on our artistic programs’.

Since then, expectations have increased.

‘One of the interesting things that’s happened over the last couple of years was the introduction of the Charities Commission,’ Tucker said.

‘One of the benefits that was touted about the Charities Commission was that it would be a one-stop-reporting-shop and that reporting requirements would be decreased.

‘I actually said to them they should be up for false and misleading advertising because in fact that’s not the case at all. Their line was that you drop your financial statements and annual reports on to our website and that would be accessible to any government department.

‘The point that I made to them was that there’s no way in the world that any government department will give up its right to extract financial information from an arts organisation just because it happens to be on the Charities Commission website. So in actual fact now organisations need to acquit not just to their funding agencies but also need to give the Charities Commission the same information.’

But will the Australia Council’s proposed changes improve things?

‘I would think probably not,’ Tucker said. ‘I think they will just require the same information from those five categories. So the people who might have been in a particular category will now be in another one. But the reporting requirements that they formally have to report against will probably be no different in the new regime.’

Tucker also voices concerns that simultaneous funding cuts redouble administrative pressures on existing staff.

‘Now that funding is strapped for staff, I think many organisations are finding that they’re actually losing track of what they need to do,’ Tucker said. ‘And then the first inkling that they’ve missed a reporting deadline is that they’re receiving breach notices and things like that. Some funding agencies are quite quick to issue breaches, which means that you don’t get any new releases until you’re up to date with your reports.’

According to Tucker, a common dilemma is when separate agencies require reports from temporally different financial ledgers.

‘An organisation could be operating on the calendar-year basis or it could be operating on a July-June basis. But if the funding agency operates on a different year then basically they need to operate two actual separate accounts, one to an agency on a calendar basis and another to the regulatory authority on a financial-year basis.

‘So they actually have to keep two separate ledgers all the time so they can run a set of financial statements that run on the calendar year or on the June-July financial year. They’re thinking on a financial-year basis and they don’t sort of realise that they could be making entries on the previous year that’s already been reported to the funding agencies on a different time frame. The amount of work required in trying to reconcile two different sets of ledgers becomes just frightful.’

Here Tucker acknowledges that the Australia Council has made some positive headway.

‘The Australia Council basically said to organisations that are in this situation – look, you continue to produce your financial statements on a July-June basis, give them to us when they’re all finalised and lodged. And we will accept that as the financial report for the previous calendar year.

‘Let’s suppose, for example, that the organisation operates on a July-June financial year, then the July-June financial report would simply show the funds that were received from July-December, and then separately the funds that were received to June.

‘Then the funding agency can actually see, well, there’s our six months, that tallies up with what we’ve got and the reporting is more simple. If only other agencies would follow that – and maybe they will – it will make it much easier,’ he said.

Sheila Hollingworth has two suggestions to improve the current system.

‘It would be really nice to know about some of the funding much further ahead than timelines often are. They’re not always advertised in plenty of time and so you’re sometimes left asking – do we have enough time to put together an application in the two weeks closing from when we’ve heard about it? So advertising well in advance would be really useful.

‘Secondly, it would be lovely if, when the application is a repeat from a previous organisation, you didn’t have to put in all the information you have in the past, you could just say “see previous application.” Because for many organisations, you’re going back to the same funder and it seems a bit painful to have to restate things over and over when they already know who we are.’

A relative new player to the funding game, Tobias Manderson-Galvin is founder and co-creative director of MKA: Theatre of New Writing. MKA is in their first year of a $40,000 triennial grant from Arts Victoria and Manderson-Galvin also has Australia Council funding for a single project.

Citing his youth and possible inexperience as an influence on his perspective, Manderson-Galvin declared: ‘I found the funding process to be relatively painless. We’d never had a grant before and it seemed they really wanted us to have it. We’d been sitting around with no money doing work for a few years and so they coached us a bit in that grant. With most grant applications, if you talked to the people in advance, are happy to coach you through it.’

Manderson-Galvin welcomes the ongoing support that comes with being inside the system.

‘Whereas with a project grant, you do a grant application, you get the money, you spend the money, you acquit it. With this one [organisational investment funding], okay, I have to report more often. But they’re much more willing to advocate for us and our relationships with other companies are better. Any company with that stamp of consistent approval is a more attractive partner for anyone else,’ he said.

Despite his general positivity towards funding agencies – ‘it seems like they’re all doing their best to make the process as pain-free as possible’ – Manderson-Galvin would like to see more rolling funds available for what he calls ‘responsive art’.

‘Our most successful work to date is a show I wrote in two-and-a-half weeks and we rehearsed for two weeks and then we put it on. By and large, there’s no real contingency for stuff like that,’ he said. However, he notes that the Australia Council have been talking about the introduction of rolling, three-monthly rounds which might be more applicable to work made ex tempore.

Fiona Menzies, CEO of Creative Partnerships Australia, speaks on behalf of funding agencies when she underscores the importance of professional conduct and accountability between organizations.‘Recipients of funding from Creative Partnerships do have to submit acquittal reports, as we are a government agency and are required to report to the Parliament and, ultimately, taxpayers and voters, on the outcomes of the grants,’ Menzies said.

‘However, we are aware of the need to not burden organisations with unnecessary red tape.

‘Therefore, we confine our acquittals to seeking evidence that the funds were spent on the activity they were given for, and information that will help us evaluate the effectiveness of the program so that we can ensure it is continually improved for the benefit of the recipients.

‘While I understand that some arts organisations, especially smaller ones, may feel reporting requirements are onerous, they are a necessary part of receiving government funding and they need to take that into account when seeking government funding.’

Indeed, arts organisations do not dispute that accountability is integral when large sums of money are involved.

‘I’m more than happy for the checks and balances to exist when it means that the work is being appropriately assessed,’ Manderson-Galvin said.

‘Red tape implies it’s all bad but I don’t know that it is,’ Hollingworth said. ‘I do think there needs to be a rigorous process. It’s just that sometimes it seems that the gatekeepers are zealously guarding the funds that are there to be distributed.’