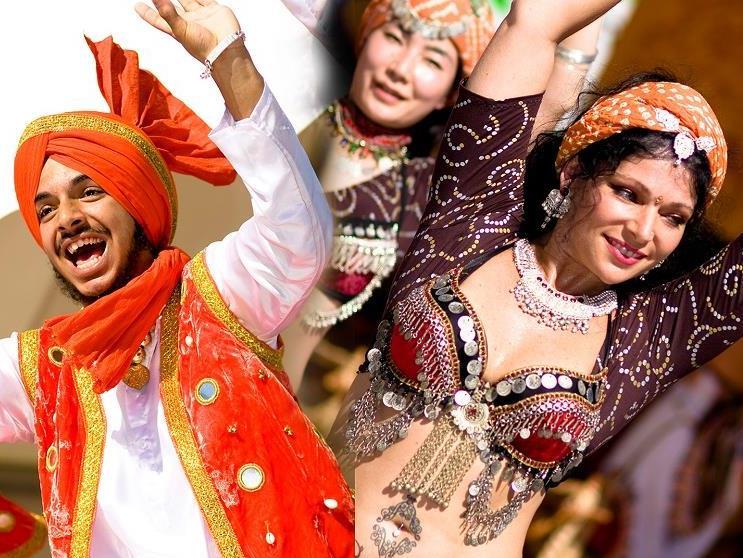

Woolgoolga Culture. Image: courtesy Coffs Harbour City Council

Comprising beaches, marine parks, rainforests and alpine regions, Coffs Coast is unique in Australia: the only intersection of sub-alpine, sub-tropical and sub-marine environments.

For travellers seeking a truly cultural retreat away from the bustle and bluster of the capital cities, Coffs Coast might just be your new favourite place.

For decades, Coffs Harbour has been a favoured town for families looking to combine the twin adventures of the Pacific Ocean and the Great Dividing Range. But the kids who used to roll up with their parents to hike the trails of Dorrigo or body-surf at Park Beach are all grown up now; and their taste in entertainment has grown up with them.

Taking this demographic shift in stride, the Coffs Coast region has with a breathtakingly diverse calendar of spring cultural events to please all ages. There’s something for everyone; from food and wine lovers to sporting enthusiasts, cultural mavens or intrepid outdoor types. The whole region is positively awash with festivals of all persuasions from now until December.

Music festivals alone include: Bellingen Music Festival (18-20 September), International Buskers Festival (20-27 September), and the Dorrigo Folk & Bluegrass Festival (13-25th October).

Rollicking tunes in idyllic bush settings aren’t to everyone’s taste so there are plenty of other choices among the ghost gums. Some holiday-makers might prefer a fishing festival, for example; or historic tall ships, cars or trains over music and performance. For the fishing types there is the Dave Irvine Snapper Classic, for the auto-inclined the Smoke on the Water Festival. The foodies will want to time a visit for seaside nosh-fest Toast Urunga on September 7, which provides both great food and entertainment.

The beloved and historic Jetty Memorial Theatre will play host to several items in the Coffs Coast roster this season, kicking off with a performance on the first of August by the Melbourne Ballet Company, followed by film festivals and theatrical productions galore.

With so much happening it would be easy to get overwhelmed, but the good people at Coffs Coast are determined to make holiday planning in the region as simple as possible. They’ve created a travel app to help visitors get the most from their limited holiday time.

There’s also a handy guide, 101 Things To Do, to help you plan your getaway with a minimum of troublesome thumb-twiddling and oohh-ahh-umming. Featuring such outdoorsy fun as the Dorrigo Skywalk, sky-diving, powerfan drops, rafting, whale-watching, and – tantalisingly – ‘crab racing’, this list highlights the diversity of entertainment on offer.

Families have long taken advantage of the unique blend of wholesome physical fun and sophisticated cultural events. But it seems travellers with the most to gain from a trip to the inspiringly pretty area are couples in need of some atmospheric rest and relaxation. For example, Coffs Coast may finally be the go-to destination for otherwise-loving couples with irreconcilable leisure differences. One can browse the exhibitions at the Coffs Harbour Regional Gallery and markets while the other flings themselves bodily from a cliff or hurtles down a dirt-biking path. Then, the happy couple can meet up at the Woolgoolga CurryFest (16 September), which is exactly what it sounds like and well worth a visit.

There’s a lot on offer for couples with hobbies in common as well, and the area is becoming increasingly popular as a wedding and honeymoon destination. The historic Bellingen main street is so storybook-lovely it positively screams to be photographed in sepia and preserved in a photo album with a sprig of local eucalyptus. The town was immortalised as a notional setting in Peter Carey’s Booker prize-winning novel Oscar and Lucinda, and the surrounding hills are dotted with towering Australian cultural figures such as David Helfgott, Russell Crowe, and Jack Thompson – all drawn to the region’s prevailing artistic and reclusive lifestyle.

There are also plenty of permanent cultural institutions. For artistic adventurers, there’s the Coffs Coast Arts Trail, featuring over 20 must-see galleries, museums, creative spaces and artist’s studios spread across Coffs Harbour and the Northern and Southern beaches.

The Coffs Harbour Regional Museum features a rich collection of maritime history, local Gumbaynggirr Indigenous culture and historical communications. The region has been populated by the Gumbaynggirr tribe for thousands of years prior to white settlement. Coffs Coast is home to Muurrbay Aboriginal Language and Culture Cooperative in Nambucca Heads, an organisation dedicated to protecting and revitalising local Aboriginal language. To learn more about the Gumbaynggirr, visitors can head to the Yarrawarra Aboriginal Cultural Centre.

To plan your cultural tour of the scenic Coffs Coast region, check out their Spring Sale – featuring great deals on flights, accommodation, and events!

And they still grow some mighty fine bananas, too.