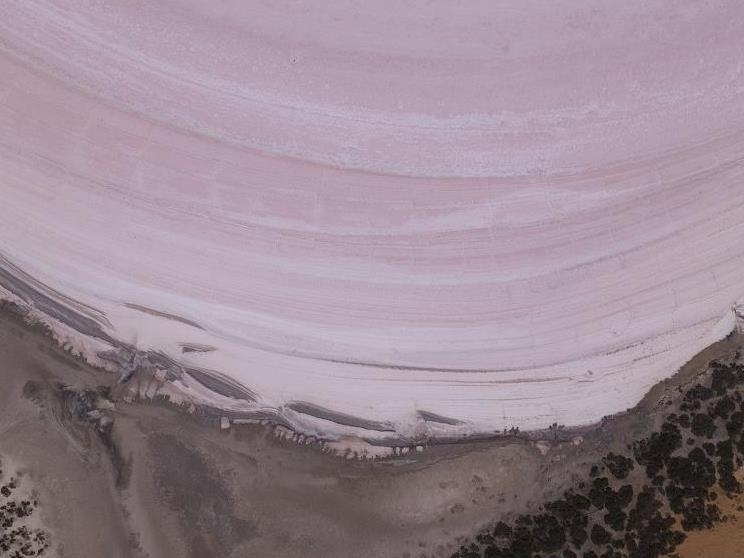

Image: The Spectral Field, 2017. Polly Stanton. HD video still.

In the early 20th Century, the cinema circuit was a kind of travelling circus, providing a cultural pathway through rural Australia.

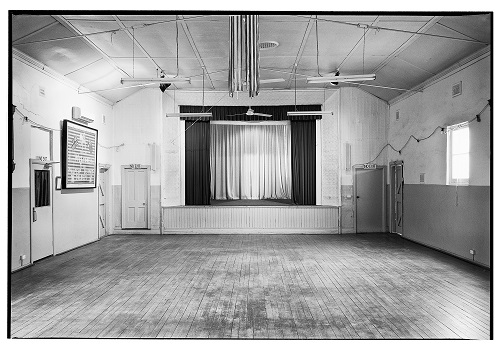

But when Sam Nightingale followed the trail to Linga, in the Mallee region of Western Victoria, he found little sense of the vitality that brought the movies to town. So he photographed an empty block.

‘At one point Linga had a community that was built around the salt harvesting that was going on – there was a post office, there was a hotel, and so on. Now, there is nothing there except for a couple of houses so what I photographed was an empty lot where a public hall used to be,’ said Nightingale.

Nightingale has followed the old cinema circuit for his photographic and video work Cinétracts which tells a story of cultural, economic and environmental change in regional Australia. It is part of the exhibition Spectral Ecologies, which explores the landscape of the Mallee through the idea of the “cinematic”.

Cinétracts follows in the footsteps of Nulty’s Pictures, a family-run enterprise that showed movies through rural Australia in the 1930s to 1950s.

The film history is a lens that provides a focus on the way our material, social and environmental worlds interact, creating changing ecologies that encompass the human and physical worlds.

In Linga’s case not only has the site where the Nulty’s once showed films disappeared, but also the whole town due to the changed economic infrastructure of the area that first relied on the salt harvesting industry of Victoria’s salt lakes.

‘The cinemas are spectres but they are subject to other spectres as well and other changing environments,’ said Nightingale.

He refers to his practice as “cinematic cartography”, operating from an interdisciplinary space that draws on critical cartography and different ways of mapping as well as the form of cinema as a social and material space.

‘I work with cinemas as a methodology and form of cartography…I have been coming to rural Victoria since about 2011, mapping out and finding the traces of cinema history in rural locations. ‘That’s my engagement – I use cinema as a way to engage with place. So it is about cinema, but it is also about so much more, about other histories, tracks and routes that exist in the landscape.’

Image: From the series Cinétracts (Spectral Ecologies), 2016. Sam Nightingale.

‘When we talk about ecology we are so often focused on the bio-physical, but ecologies are entanglements of different forms brought together. They are as much about material, whether that is the land and the natural ecology if you like, as they are about the people who are a part of that land and cinema as a form of social gathering…it is really thinking about ecology in an expanded sense.’

The story of the Nulty’s is also the story of early cultural entrepreneurship. Jim Nulty, father of the Nulty Family, received a projector as part payment for a car repair job he did at his garage in Walpeup. ‘He first used this projector in the Memorial Hall in Walpeup, after that he took the show on the road in the back of his Bedford van driving all over the Mallee,’ said Nightingale.

Many of the towns and settlements the Nulty’s visited didn’t have their own electricity at the time so Jim Nulty would rig up the projector to the gear box of the Bedford van, run the van engine and this would provide enough electricity to power the projector.

A cinematic eye

Curator Bridget Crone said the cinematic-theme enabled artists and audiences to think differently about the landscape.

‘Often in art we hear lots of talk about site specificity and site specific practices. For us, the idea of cinematic seeing is a way to think about mapping differently.’

Polly Stanton’s video The Spectral Field explores the tension between seeing from a distance and being immersed up close. In the first drone footage capturing a birds-eye view of Pink Lakes, salt lakes situated in the Murray Sunset National Park, there is a pulling out and closing in that playfully mimics cinematic tropes of panoramic landscapes and the close up.

The drone footage is juxtaposed with close up imagery and field recordings that immerse the viewer. This process produces another form of “cinematic cartography” that explores the way the visual languages of cinema can be used to map the landscape in a new way.

Image: Screen Memories, 2017. Sam Nightingale.

Placing Nightingale and Stanton’s work in conversation with one another creates a space where landscape is approached through cinema, but in an entirely different way than the viewer is accustomed to. It carefully untimes permanence, or at least the cinematic extension of its shape in our human psyche, as often associated with forms of documentation and the expectation of the landscape as immovable and stable. It does this by referring instead to the capacity of images to present us with the spectres of history and, particularly in Stanton’s work, to completely immerse us in the physical world we live in through different ways of seeing.

Spectral Ecologies includes a series of public events in Ouyen and Robinvale organised in partnership with the Ouyen & District History and Genealogy Centre and Euston/Robinvale Historical Society, 7, 8 and 9 April 2017.

The exhibition is on until 18 June 2017 at Mildura Arts Centre. More information here: http://www.milduraartscentre.com.au/Whats-On/Exhibitions/Spectral-Ecologies.aspx