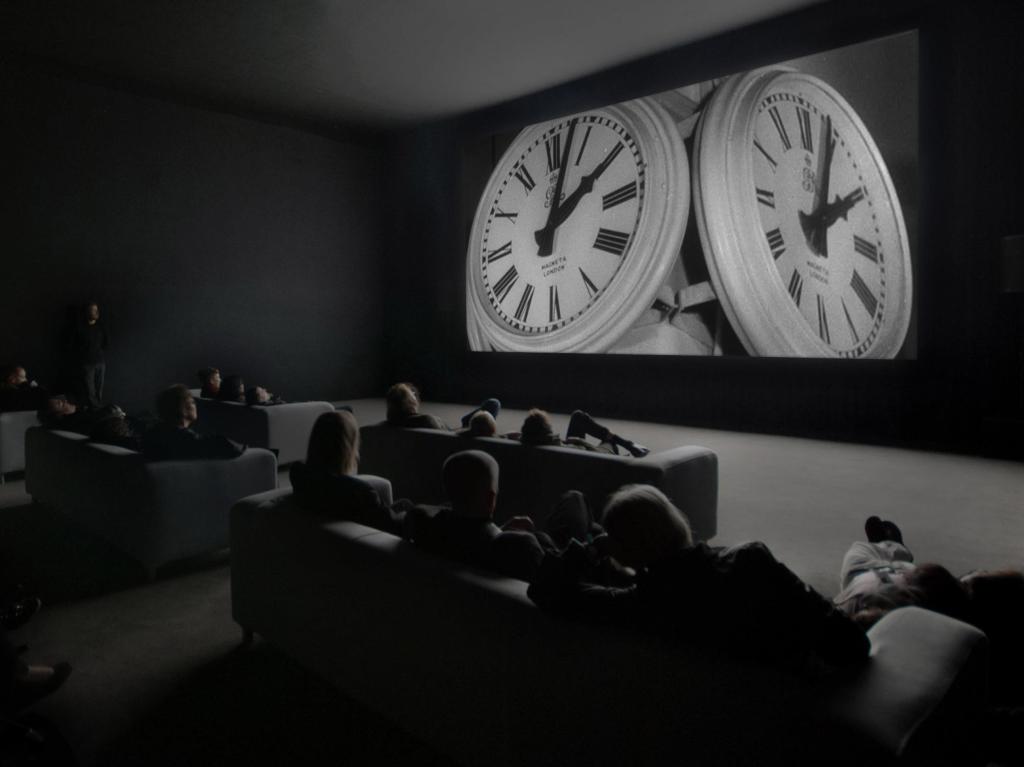

Christian Marclay: The Clock 2010. Courtesy White Cube, photograph by Ben Westoby.

Video artist Christian Marclay’s installation The Clock is a 24-hour montage of some 12,000 moments from film and television that references time by the minute and functions as a clock itself, so that the time you see on screen is the actual time of where you are. Instantly immersive and entertaining, the fact that The Clock is a work of art may be overlooked or underplayed, but it is exactly that, opening in London in October 2010, not at a cinema but a gallery. Although its medium is film, it is not a film but an experience of time in real time. Its effect is to turn time into a physical sensation, by way of setting your body clock to its rhythms.

As a viewer, you submit yourself to the experience, almost like a willing participant in an experiment, not knowing from minute to minute what will come next but relishing the fact that time will tick over and something new will appear. Already it seems that we can’t have enough time, provided that whatever it is will happen to someone else and not us, on our white IKEA couch, viewing from a safe distance.

Left with the metronomic device, our thoughts start to roam and wander, although there is more action on screen than you will find in any film you’ll see, and we turn inside our heads for the narrative that is missing. It’s then that The Clock becomes an exercise in meditation and reflection in spite of the propulsive dynamic of the installation. We soon become open to points of paradox, about the nature of time or the ability to be in and out of yourself at the same time.

Strange as it seems, with time on the march you find yourself with all the time in the world and having time to think. The realisation is immensely liberating and satisfying. Even more so when there is no weight or value to those thoughts, other than the fact that they all come by way of the constant images before your eyes and the continual reminder of the exact time on screen and in life.

Christian Marclay: The Clock 2010. Courtesy White Cube, London and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

For my first experience of The Clock I set myself two hours, from 10.35 am to 12.35 pm. I don’t intend to give every thought that passed through my mind by the notes I kept, but I can say that I felt fully refreshed at the end of the two hours and entirely engaged in every minute of those two hours. Only by a conscious act of will did I raise myself from my seat to leave the gallery, and then be instantly and acutely aware of time pieces all around me, as if my senses were set to look for them in digital displays or analogue movements. I was conditioned to the passage of time and simultaneously mindful of how time flies.

That was my experience, at least. Yours will be bound to be different, as will mine the next time I come and stay for four hours to see if what I learnt in two hours still holds true. At the time though, and shortly into my visit, I felt that I could confidently attempt a whole day of viewing during ACMI hours of 10.00 am to 5.00 pm and by the end I was contemplating the weekly 24-hour screening on a Thursday. Time did not drag in the least; in fact it felt frictionless.

The mind can’t help but look for meaning, even if there is none intended. Thoughts come and go, more often than the minutes on screen. You begin to notice things. There is a historical sweep of fashions, cars, technologies, language and manners. You switch from English to French, Italian, Arabic, Swedish and Japanese without blinking. You look for more proof that Big Ben is easily the most referenced timekeeper in cinema. Actors almost audition for you, and from the fragments of screen time they have you find favourites, old and new. You pick up on films that you’ve never heard of but follow up after, such as Johnny Cash as a sadistic killer in Five Minutes to Live. You formulate a thesis that drama relies on time far more than comedy, judging by the scant six appearances that comedians make over the 120 minutes. You marvel at the random juxtapositions and seeming coincidences. You examine the nature of time and finally, you see time as a character in itself, the one constant throughout the viewing and our constant companion in life. These are but some of the amusements you provide yourself by suggestion of the snippets on screen and you appreciate that half the fun is inside your head.

Christian Marclay: The Clock 2010. Courtesy White Cube, London and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

The Clock is art of the highest order. It is simple in concept but profound in effect. Technically it is a masterpiece of sound and editing. By design it has no meaning, but it is open to an infinite number of reactions and responses. It challenges the notion of a review, because few will have seen the installation in its entirety yet feel justified in providing a critique, whereas no one would think to review a portion of a painting or a chapter of a book as a legitimate comment on their whole.

As few people will have read James Joyce’s Ulysses from cover to cover, they will still have their opinions. When you consider that the novel also follows a single day, in its case a day in the life of one man, Leopold Bloom, in one place, Dublin,The Clock can be considered as an update of that artistic device, not in words but in moving images. It expands the location to the whole world and casts human behaviour as the lead character. You could call The Clock the Ulysses of our times.

Rating: 5 stars ★★★★★

Christian Marclay: The Clock

Artist: Christian Marclay

Curator: Fiona Trigg

23 January – 10 March 2019

ACMI, Melbourne