To start with, the program was free, which, in this critic’s most humble opinion, can only be a good thing. The Sydney Philharmonia Choir have been consistently charging for their programs, yet – unless this was a one-off – they have come into line with the Sydney Symphony and the Australian Chamber Orchestra, and made their programs free for one and all. The layout itself, too, is different, and far more modern and pleasant and wonderful than what came before. Yet, there were problems.

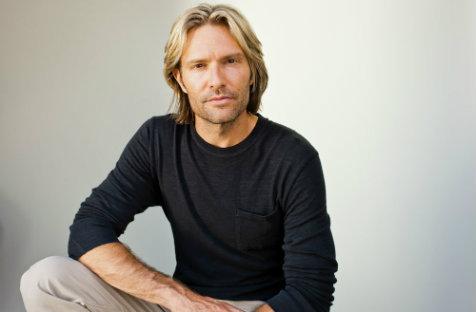

The concert – Light and Gold: The Music of Eric Whitacre – featured Whitacre himself as conductor for the evening. He was a surprisingly lively and charismatic presence on stage, constantly giving, in between pieces, the audience some background on what they were about to hear, such as the story behind it, or what he tried to achieve in the music, and so on. And at many points during the night, Whitacre would make mention of a ‘translation’ or the ‘words’ to a piece, saying ‘I think they’re in your programs’. No. They weren’t. And I know they weren’t, because I looked, many times. Indeed, they would’ve been quite helpful.

They would have been very helpful, for instance, during his five song cycle entitled The City and the Sea, where five poems of E.E. Cummings were set to music. Unfortunately – and the venue, the Concert Hall of the Sydney Opera House, is partly to blame for this – the words coming from the choir were unintelligible for a large portion of it, and so one had very little idea of what was being sung, even if it was in English. So one hopes that future programs do bother to include the translations in them.

Nevertheless, this was still a surprisingly wonderful concert, especially considering that the music, with two exceptions, was all by the same composer. Whitacre is perhaps most famous for his YouTube experiment a few years ago, where he made a virtual choir sing his most famous piece – Lux Aurumque – online. This was achieved by having people sing their parts alone in their bedrooms, or bathrooms, or what have you, and then uploading that to YouTube. Whitacre and his team then sorted through all of them, cleared up the sound a bit, and mashed it all together into a glorious concoction of voices. And it was this piece (sans the internet this time) that we began with.

It’s beauty, as anyone who has heard it before would know, is stunning, with its use of those spine-tingling harmonies that only the human voice can achieve to such effect on the general audience member. Three traditional spiritual songs came next – arranged by Moses Hogan – and what they lacked in vim at the start of each, they made up for with their power at the end.

Vox – the younger choir – left, to be replaced by the Symphony Chorus, who tackled The Seal Lullaby, the text taken from the start of a Rudyard Kipling story – beautiful once more. The City and the Sea (mentioned before) was not up to the same level, however. One had heard the Choir perform the fifth poem – little man in a hurry – a while ago, and I found it quite enjoyable then, but this time around, even though it was the best of the lot, it was rather disappointing. Higher, Faster, Stronger saw the return of Vox (while their counterparts remained), and consisted more of sheer energy than musical ecstasy. The piece, based on the motto of the Olympics, had much inertia, but didn’t quite hit the heights one was expecting it to.

After the interval came the Symphony Chorus, and Five Hebrew Love Songs, and even though one had very little idea what was being sung, the overall effect was astounding. There is a universe in each of these pieces (entitled ‘A picture’, ‘Light bride’, ‘Mostly’, ‘What snow!’, and ‘Tenderness’), and the entirety was spellbinding. The Chelsea Carol made use of the organ, but was rather more sombre than one might have suspected for a carol. A Boy and a Girl swapped the Chorus for Vox, and was another highlight, using silence, as Whitacre explained, as a motif, and managing to succeed at it, unlike many other pieces where the tension slackens beyond repair.

Come, Sweet Death, by Bach, with an idea conceived by Edwin London, was an experiment where Bach’s words and music were sung once, then again, but the second time with every member of the choir singing at a different pace. (Some simple hand movements let the audience know where each member was up to, as well.) The effect was quite weird, quite spooky, in a way, and somewhat reminiscent of Ligeti’s cries in the 2001: A Space Odyssey soundtrack, though a tad less hellish.

Cloudburst was the penultimate work, bringing nature to the fore, with a rainstorm described by a smattering of bells rung by a selection of the members of Vox, and made for quite the special moment, even if it perhaps took a bit too long to get where it was going. The Symphony Chorus returned to sing Sleep, which, while powerful, didn’t eclipse some of the other pieces of the night.

Overall, a fine and consistently engaging concert.

Rating: 4 stars out of 5

Light and Gold

Sydney Philharmonia Choir

Eric Whitacre (conductor), Symphony Chorus, Vox, Synergy Percussion, The Acacia Quartet, Christopher Carter (piano and organ)

Eric Whitacre – Lux Aurumque

3 Traditional Spirituals (arranged by Moses Hogan)

Eric Whitacre – The Seal Lullaby

Eric Whitacre – The City and the Sea

Eric Whitacre – Higher, Faster, Stronger

Eric Whitacre – Five Hebrew Love Songs

Eric Whitacre – The Chelsea Carol

Eric Whitacre – A Boy and a Girl

Johann Sebastian Bach/Edwin London – Come, Sweet Death

Eric Whitacre – Cloudburst

Eric Whitacre – Sleep

Concert Hall, Sydney Opera House

30 March