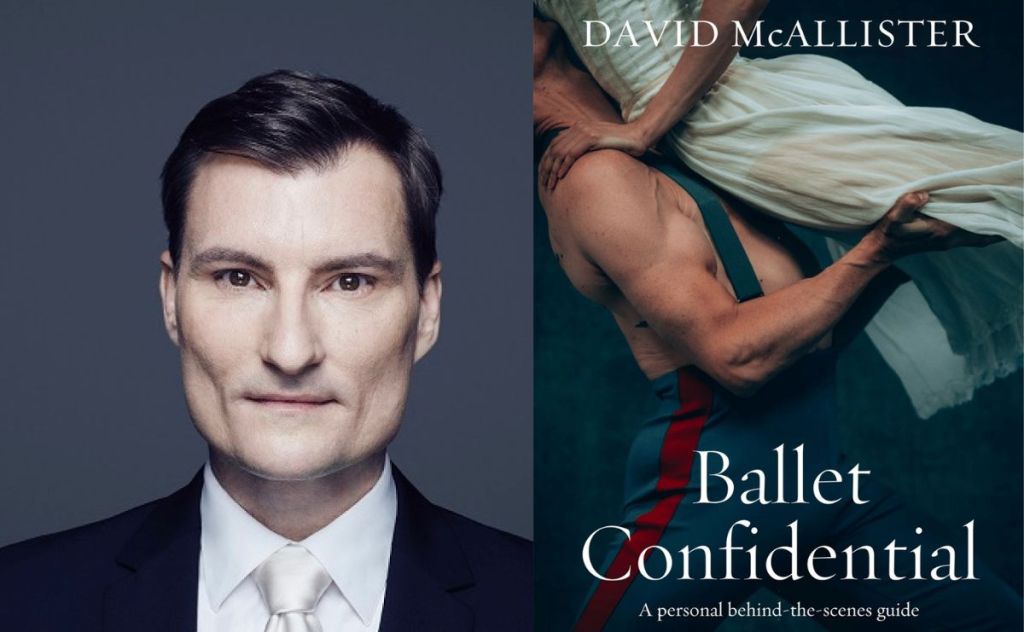

A new chapter in the growing catalogue of ballet memoirs, Ballet Confidential, written by former Australian Ballet director, David McAllister, promises to have you ‘romping through the unique and wondrous world of ballet’. But what is so unique and wondrous in his account that has not been uncovered before? One thing McAllister bravely sets out to do is “demystify” ballet and, with that, “debunk” common, in his view, misrepresentations of the art form, including charges of “gender bias”.

This is a bold claim, and one that seems to discount the more recent wave of ballet memoirs, mostly coming from female dancers, exposing ballet as rife with gendered abuse culture, such as Alice Robb’s Don’t Think Dear and Georgina Pazcoguin’s Swan Dive.

In the first chapter, McAllister seems to be trying hard to present the ballet world in an accessible, unthreatening way, but the resonance of perfectionism and elitism in ballet still arise undeniably within the work.

McAllister points out understanding ballet is the key to appreciating ballet in the same way that one must understand how to play sports in order to appreciate them. He mentions playing cricket with his dad in hot Perth summers. He describes first seeing Rudolf Nureyev as a guest artist in The Australian Ballet’s Don Quioxte as his ‘miracle at Fatima moment’, revealing his Catholic upbringing.

With lively prose he explains what sets ballet dancers apart from athletes: their artistry and their ability to ‘hold a mirror’ up to society through this. He develops his argument for the performing arts being a less elitist form than sports, as he praises the centrality of performance arts in ancient Indigenous culture for storytelling and expression of collective purpose.

How in the case of ballet then, could dance have steered so far away from its elemental beginnings, as an equalising art form? Perhaps because ballet, unlike other forms of dance, was always tied to class, gender and aesthetic ideals or “habitus” in philosopher Pierre Bourdieu’s theory. McAllister’s argument that ballet is for all is great as an ideal to work towards, but we are not quite there yet. Perhaps this work is a step in the right direction.

The substantial first section of the book reads like a manifesto for ballet’s relevance to a wide audience, as McAllister writes: ‘Words like “elitist”, “irrelevant” and “boring” are often flung our way and yet hordes of young people from all socioeconomic backgrounds roll up to dance classes across the world each week.’

As a hopelessly devoted converted balletomane, having danced since I was a child, I don’t need persuasion to love ballet. I would rather less on this and more getting straight into his life story as a dancer and director – the reason, I suspect, many will pick up the book. Thankfully, McAllister gets to this colourful story once he’s got the official history of ballet out of the way.

McAllister proceeds to challenge the hackneyed queries he gets at dinner parties and challenge the common myths surrounding ballet dancers’ lives. The most amusing of these is perhaps ‘do you get aroused when doing a pas de deux?’, which McAllister emphatically denies, pointing out that the technical overwhelm of dancing the pas de deux correctly impedes desirous thoughts. Another is the cliché of ballet dancers ‘torturing themselves for their art’. McAllister says, ‘For me, the studio was like my own personal amusement arcade (yes, I am that old).’

Reading this book is like having a warm, convivial cup of tea with McAllister, as he muses about his life, rather than the shocking, misery memoir style of ballet autobiography we have seen more commonly – at least since Gelsey Kirkland wrote Dancing on My Grave in the mid-80s. Readers may find the lack of neurosis and anguish surprising for the genre, but McAllister’s account of his life as a ballet dancer and director is frank and entertaining, a kind of behind-the-scenes guide to ballet for people who are curious.

Read: Book review: Fake Heroes, Otto English

McAllister’s book makes for an amusing, gentle and affable entrance into the ballet world, and insight into his sunny perspective. It’s an enjoyable ballet memoir overall, contrasting with some more caustic ones of late.

Ballet Confidential, David McAllister

Publisher: Thames & Hudson Australia

ISBN: 9781760763251

Hardback: 256pp

RRP: $34.99

Publication: 25 July 2023

This review is published under the Amplify Collective, an initiative supported by The Walkley Foundation and made possible through funding from the Meta Australian News Fund.