Most of us get the green thing. Saving koalas is a Good Thing. The natural environment matters. We recycle, save water and care about the green places around us.

There is a green building council, a Green Cross, organisations such as Greening Australia and even a Green political party. There is an organisation for green skills, and you can buy green power.

Every few years we report on the State of the Environment where we worry about feral animals, die back, water conservation, pollution. Somewhere in the middle of that big thick report is a chapter on cultural heritage – the brown stuff if you like. Discounting for a moment that part of that chapter focuses on natural (aka green) heritage, the report talks about historic and indigenous heritage.

What does this mean? Protected sites and indigenous languages, mainly. Not museums or museum collections, memories or stories, traditional music or ordinary places that happen to matter.

Data in this section of the report is hard to come by – but we learn that only 3-6 of the 180 or so indigenous languages are safe – the rest are no longer fully spoken or endangered in some way or another. Heritage sites seem to be ok, except that “there is a substantial gap in the process of monitoring the historic environment”. There is no nationally coordinated inventory of significant Indigenous places. Survey and assessment programs for Indigenous heritage only take place if there is a threat. At the same time resources are declining, and “community perceptions of the value of heritage as a public good are not reflected in public sector resourcing or incentives for private owners”.

Australia has an international reputation for brave heritage practice such as the battles for the Rocks. The values-led approaches developed in Australia are seen internationally as wonderful examples of creative thinking. But somehow, back home, we hate our heritage. National Trusts – those great heritage advocates – are struggling. Funding for heritage grants and organisations lags well behind that for natural conservation

Meanwhile, brave little heritage buildings crouch awkwardly between the towers that will make Sydney look just like Singapore (or Hong Kong, or Dubai). The Federation houses or Sydney-school architecture that shaped our suburbs is gradually being eroded. We keep plaques and markers rather than real buildings.

If you want to conserve natural heritage there are incentives to help buy land and maintain it. If you want to conserve an older building – you start with your hands tied behind your back economically.

There are many incentives to demolish buildings: It’s easier to get a good energy rating on new buildings; mortgages are cheaper and land is sometimes worth more without an old building on it.

Even if you do the right thing by your house and your suburb, the chances are the new planning regime that is coming in NSW will mean that your neighbours certainly don’t have to.

Cultural heritage sits in that funny wasteland between the environment and the arts – there always seem to be hundreds of reasons why cultural heritage is not eligible for environmental initiatives. But you find me a natural site that does not have an element of culture to it. Even the 30,000 years of land management that has shaped our environment today is ultimately a cultural artefact..

Whatever politicians would like you to believe – people actually care about their cultural heritage. They care about their local area and neighbourhoods. They think it is important for children to learn about their history; watch television programs about history and heritage, visit museums and heritage sites. Indigenous people who are in touch with their culture and heritage are happier and healthier.

The explosion in genealogy is all part of a new interest in finding out about our own past and our own stories. Where an older generation loved Georgian houses and Paddington terraces, a younger generation is rediscovering the architecture, culture and interiors of the fifties and sixties (and whiskers!). The sheer level of enthusiasm for old cars, boats, trains, agricultural equipment, tanks is palpable. This enthusiasm is all part of our desire to embrace our heritage.

So – what do we do?

- Change the rules to acknowledge that cultural heritage is of core relevance to caring for our environment, including heritage worth as a factor in eligibility for environmental grants.

- Create a level playing field. Deal with the regulations, incentives, tax breaks and rules that make it so much harder to save an old building than to knock it down and build a new one.

- Be out and proud.Australia has a complex and challenging cultural heritage. Let’s be proud of it – warts and all.

- Use the ‘H’ word in public.There is a world of developers out there who want you to think heritage is old, dirty, boring and environmentally disastrous. In fact older is actually greener:preserving buildings reduces waste andtakes advantage of embodied energy. Often those older buildings perform quite well in green terms.

- Join up.Your local society, the National Trust, your museum friends, the tweed riders or whoever. And if you don’t like what they are talking about, change the agenda.Just be part of it.

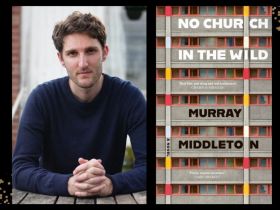

Photo by National Trust Victoria: Rippon Lea Historic House & Gardens