‘When working with an Indigenous community, be prepared to forget all your previous experience and knowledge because you know nothing about the issues in that particular community.’

So advised Frederick Copperwaite, co-founder and Artistic Director of Moogahlin Performing Arts Company, at the MPA Education Network forum, held in Sydney last month.

A Bunuba man of the Fitzroy Crossing region of the South West Kimberley, WA, Coppeerwaite graduated as an actor from the Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts in 1987 and has extensive experience in all forms of theatre, television and film performance, including in A Country Practice, Fields of Fire, Barlow and Chambers, Blue Heelers, Heartbreak High, GP, Police Rescue, All Saints, Code Red, Water Rats and the international feature films Sniper, Dark City and Mr Nice Guy.

At a session focusing on working with Indigenous artists, communities and audiences, he pointed out that every community will have different issues, so it is absolutely crucial to tailor your course to that community.

‘You can’t put it all in one basket,’ he said. He urged anyone planning to work with Indigenous communities to talk to teachers on the ground and community members, so that the course being planned is alive and relevant. It’s all about reconciliation—which, although ‘a government buzz word’ is actually just about getting to know people.

‘Aboriginal people are not a project,’ said Copperwaite. He pointed out that when people go into communities they have a huge responsibility. They need to be interested in the cultural exchange taking place, and engage with sensitivity.

Copperwaite has taught young Aboriginal people and communities, particularly in the Kimberley and East Arnhem Land. He has also worked in regional and urban NSW, including with Redfern Community Centre—not to mention his 35 years’ experience teaching speech and drama to people ranging from young children to professional actors.

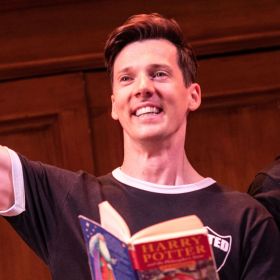

‘It’s about an open and equitable exchange where the community has to have ownership.’ James Evans, resident artist in education from Bell Shakespeare, agrees, pointing out that when they run masterclasses in remote communities, it is a cultural exchange—‘it’s not just about us dropping a performance on a community’.

At the MPA Education Network forum, Evans took delegates through the kinds of protocols that Bell has developed when working in remote communities. Protocols are very important when working with older children and adults. Bell has found that kids in primary school are more open and accepting, but once they reach high school, the concept of shame is clearly articulated and can be a barrier to them getting involved.

Bell’s strategies include:

- Teacher-in-role activities: we make sure the teacher is immersed in the group and does not position themselves outside it.

- We make sunglasses, masks or scarves available for older children to wear— which gave them licence to ‘dive in and play’.

- We talk about ourselves—and we take photos of our families, earning trust and connection.

- We talk about Shakespeare in the same way—who he was and where he came from.

Why even think about performing Shakespeare—a dead, white, Western male—in Indigenous communities?’ Joanna Erskine, Head of Education at Bell, answered her own question. Because, she said, it’s all about storytelling, the flexibility of language and the universality of the themes.

‘We want to use his stories to create self-reflective learning experiences. Sometimes we don’t even use the word “Shakespeare”’, she said.

In Tennant Creek, Bell is strengthening its ties with the whole community. A study by Educational Transformations, which evaluated students and teachers from 19 schools (including at Tennant Creek) who had taken part in Bell Shakespeare residencies, has shown very positive, concrete outcomes, including two children gaining entrance to the Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts.

According to author Dr Tanya Vaughan, students who participated had significantly increased attendance, decreased anger, increased innovation and improved attitudes to English.

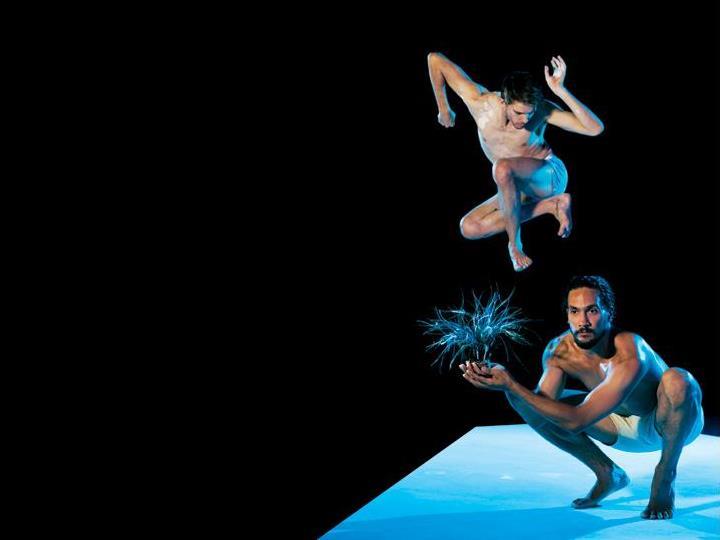

Bell is one of several major performing arts companies working intensively with Aboriginal students. Bangarra’s Rekindling Program was launched earlier this year and is being run in Wellington, Kempsey and Moree, New South Wales, with plans to extend into Queensland next year and then other parts of Australia.

Short-term outcomes are for participants to tell their own stories, with their own cultural reference points and share their experiences.

‘Long-term outcomes,’ said Bangarra’s Youth Program Director, Sidney Saltner, ‘are for participants to build long-term self-esteem, pride in communities and selves, express their culture, improve access to vocational pathways and develop leadership skills.’

The Australian Ballet delivered the Young Aboriginal Women’s program for 20 students in 2013. Each section of the program focused on learning attributes though a range of dance and craft workshops that had a primary goal including ‘learning how to learn’

Helen Cameron, the Ballet’s head of education, said the Ballet did a survey based on learning outcomes assessed by the program participants and found very positive response for: Posture (19/20), movement memory (stickability) (16/20), motivation (19/20), balance (20/20), energy (20/20), reflective thinking (15/20), body parts (19/20), listening skills (20/20).

In fact, in the three months since the program finished, students have demonstrated a higher degree of motivation in their dance-learning and have been more attentive in class across all subjects. Students unanimously recommended that the program happens every year, either at Mooroopna Secondary College or a three-day residency program at The Australian Ballet for 20 Wannik Dance Academy students as well as work experience placement for two Year 10 students at the Ballet.

Noel Pearson, Director of the Cape York Institute, agrees that the value of an arts education is much more than just about the arts. ‘Our academy [the Cape York Aboriginal Australian Academy] is committed to “concerted cultivation”, and to exposing our students to opportunities taken for granted by middle-class students in urban Australia,’ he said in a recent article in The Australian (4/7/13). ‘Music is critical to education. When I told the founder of Direct Instruction, Siegfried Engelmann, of our plans to introduce his program in Cape York, he exhorted me to ensure we had lots of music in our schools. Music undoubtedly is crucial to the intellectual development of children. ‘

In all the debates about Gonski and literacy and numeracy, there is hardly a word said about music. We need music teachers in disadvantaged schools as urgently as we need maths and English teachers.’ But how that education is delivered is critical to its success. After initially planning to take Shakespeare into Yipirinya School in Alice Springs, the company has decided that it’s more important for kids to learn about self-expression and self-reflection. So they will be teaching skills for communication and for life

As Fred Copperwaite mentioned, flexibility is the key. ‘Family business takes priority over this work,’ Fred said. ‘Non-Aboriginal people have that distinction between private and public work, but Aboriginal people don’t—it’s all the same stuff.’ Fred also urged companies to employ Aboriginal teachers in their work—they’ll get much more access and it breaks down the common perception that opera, music, dance and theatre are for middle-class white people. ‘And you need cultural consultants—every company I work with has used them, so find them in the community or employ them before you go.’