Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders are advised that this article contains references to a person who has died.

Kelli Cole tells ArtsHub, ‘I was really determined to get this work.’ The Warumungu/Luritja curator is talking about an expansive collection of painted panels known as the Summer Project. It sits at the entrance to the National Gallery of Australia’s new Emily Kam Kngwarray exhibition, which opens today (1 December).

‘We wanted to include this to reposition her back in community,’ continues Cole. ‘It was really important to include.’ A salon hang of the canvases painted in 1988-89 by a group of Anmatyerr and Alyawarr women sweep around the first wall of the new Kngwarray retrospective. One is positioned aside Emu Woman 1988-89. It was the cover of the original exhibition catalogue for the Summer Project, and it is our point of introduction.

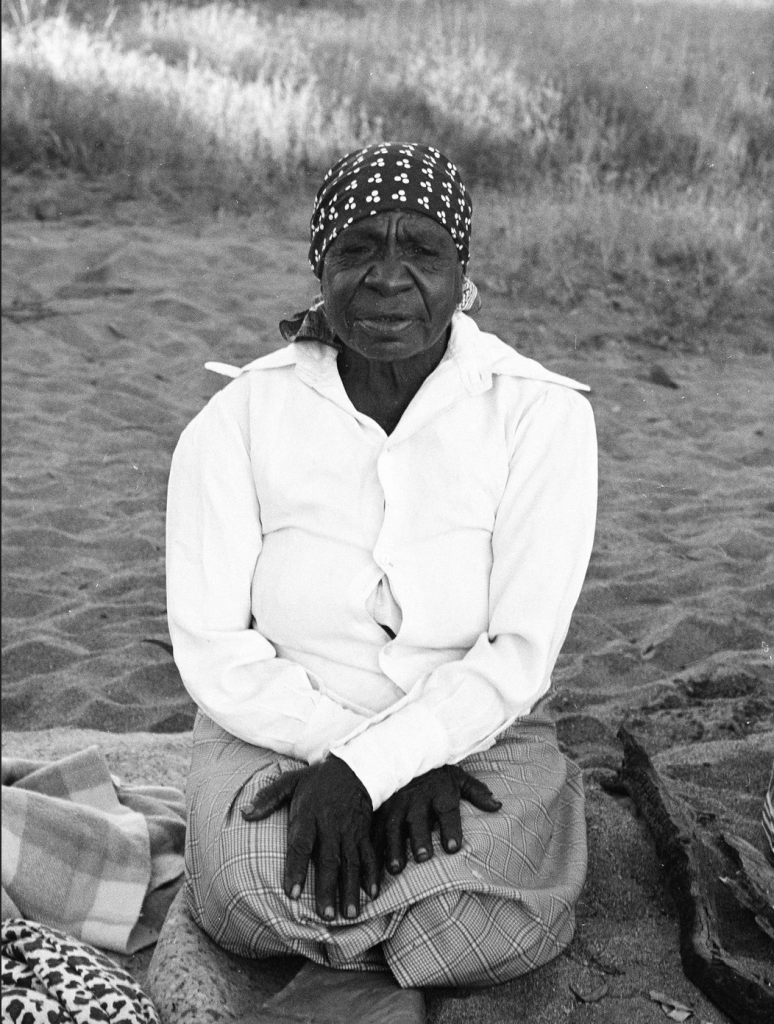

That axis of Country and community is central to this exhibition. One has to remember that Kngwarray was already a senior Anmatyerr woman before she started making art in the mid 1970s. And when she did, she was 63, and it was 11 years of making batiks first before she even started painting on canvas at 75.

This repositioning of our knowledge of Kngwarray runs right across this exhibition, as does a respect around language and the use of her name. Cole says the exhibition is deliberately a, ‘reframing, repositioning and remembering that she was never alone’.

‘She never left the community, even when she became this big, significant, international artist.’

While this is hardly the debut Kngwarray survey, it is the first since 2008, and the first paid “blockbuster” exhibition at the National Gallery by a First Nations artist, female or not.

Jump to:

Back to batiks and basics

Cole and co-curator Hetti Perkins (Arrernte and Kalkadoon peoples) have a history of curating special projects for the NGA. In fact, they have both largely lived at Alice Springs over the past two years working towards this exhibition, consulting extensively with Kngwarray’s family and community, along with linguist Dr Jennifer Green.

That sense of community is ever present here. Viewers move from that first goose-bump bang of the Summer Project into a gallery where a collection of batiks float central to the space. The earliest was made in 1977. They are hung alongside the paintings in three of the six galleries, their sight lines always a connecting thread across all the spaces, grounding her most recognisable works with their origins.

Part of the shift away from batiks for Kngwarray was about conservation. The process involves a lot of water, and you have to remember Utopia and its surrounding homelands are in the Central Desert, and water is a precious resource.

Perkins recalls Kngwarray saying, ‘Enough now, because too much rain, too much wasting.’

Some of the first paintings that viewers encounter demonstrate a foundation that sits across all that follows. A suite of three small paintings use the gesture of applying women’s body paint. ‘When we look at these, you can see where her hand swept across the chest, across the breast and across the arms, and that’s a beautiful painting,’ says Cole.

‘The thing about these paintings is knowledge. She had painted the breast of many young women for such a long period of time, even before she started working in the batik medium or painting. So when people say, “How did she paint these paintings?“ this was something that was within her,’ continues Cole.

Those gestural lines are what have made Kngwarray’s paintings internationally celebrated and shown across major exhibitions, including the Venice Biennale. Indeed, with the opening of the exhibition this week, was the announcement that it will travel to London to the Tate Modern in 2025.

Kngwarray, not Emily

What’s the big point of difference?

Cole tells ArtsHub: ‘It’s not that we’ve done anything different with hanging. Let’s be honest, this is the same show as what’s been done previously. But what we have done is, we’ve changed the language in how we talk about her with a respect that she always deserved, and back to being recognised as an Aboriginal woman. We wanted to give her that voice that, I think, was removed because it came to always be about her paintings.’

‘I try not to use “Emily” too much,’ continues Cole. ‘You don’t hear people say “Tom” for Tom Roberts. We’ve given this respect to men more than we do for women. You hear a lot of people say, “I’ve got an Emily”, but no one really ever says her [family] name. It’s not that they can’t say it, because we learn foreign names all the time. We’re trying to circle back to her name.

‘Kngwarray was born before colonisation really hit her Country, and was given the name “Emily”. ‘It’s actually redirecting people. And the whole thing about this exhibition, that we’re trying to do differently, is all about repositioning. And this should be an exhibition of change,’ Cole adds.

This builds upon the Central & Eastern Anmatyerr to English dictionary, which was published in 2010. However, many collecting institutions have been slow in adopting the correct spelling (formerly Emily Kame Kngwarraye).

Coles says these choices are in part informed by the strength of woman Aboriginal curators who have emerged, but also the founding of the Utopia Art Centre four years ago, which plays a great role in moderating the desires of the community.

What’s in this exhibition, and how does it present that different viewpoint?

The exhibition has been hung in a semi-chronological manner. In the first gallery, alongside the aforementioned batiks and ceremonial paintings, are paintings that are more closely in sync with that Western Desert iconography that was emerging in the 1980s. And, as we move into the exhibition, viewers are witness to how Kngwarray increasingly distills that iconography into her own visual language or style.

The second gallery, again with a major batik floating centrally, looks at her painting of bush food of Alhalker Country. Here the new acquisition Alhalker – my Country 1992 (purchased last year to mark the Gallery’s 40th anniversary) hangs. It is one of two pieces acquired, the other Untitled (awely) 1994 is presented later in the show.

The next gallery is dominated by her 22-panel landscape The Alhalker Suite 1993. It transfers a sense of the enormity of country and its impact. It has a physicality – you have to walk along it – to truly take it in, pushing and pulling the viewer in and out along its course of colourful lines and forms.

It is followed with another suite of batiks continuing to pull the viewer through the exhibition and constantly grounding audiences back to those roots. It seemingly forces viewers not to forget. Cole tells ArtsHub: ‘Everything came back to that – that the touch of the hand, the way she moved her hand in these batiks, and takes that through into these linear works, into the painting.’

Also in this space is a rare work, one of the last Kngwarray made in 1996, shortly before her death. Featuring strong purple lines on an ochre ground, it was painted on the banks of the creek and is ‘explosive with purpose,’ says Cole. Despite its abstraction of entangled lines, ‘you still see those yams, even though it’s more rigid than the others. But that yam reference remains – it is so important to the end,’ she adds.

There is also a painting hung opposite where Kngwarray has included her own handprints in an act of agency over her work, and another that speaks to the lines of body scarring with sorry business. These offer moments of pause, and nuance across this exhibition. There are also moments of spectacle – those monumental paintings such as Yam awely (1995) with its dazzling warm colours, and in contrast to the epic black and white painting which viewers finish on, Big Yam Dreaming (1995).

Cole concludes, ‘The presence of this old lady within this beautiful National Gallery, it vibrates with energy… There’s a pulsing of the beautiful dots. And then you’ll see the gorgeous lines, which are very rhythmic, credible listeners.’

This is a truly beautiful exhibition, and Kngwarray’s work continues to have a freshness for both fans, and new audiences to her work.

Kngwarray was born around 1914 in her Country, Alhalker.

Emily Kam Kngwarray

Curators: Kelli Cole (Warumungu and Luritja peoples, Curator, Special Projects, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art) and Hetti Perkins (Arrernte and Kalkadoon peoples, Senior Curator at Large, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art)

National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

2 December 2023 to 28 April 2024

Ticketed.

The exhibition will tour to Tate Modern, London in 2025.