Jordan Wolfson was a name that not many Australians had heard of – well, that was before 2019 when news circulated that the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) had commissioned a new robotic sculpture by Wolfson for its Collection – valued at $6.67 million.

That installation, Body Sculpture, has been revealed today (8 December), after a slight setback caused by the pandemic (it was originally slated to be unveiled in 2021). Time, in some ways, has softened the piece. It no longer is embedded with face recognition technology and tracking – as was originally conceived and consistent with Wolfson’s preceding works. It is also less gender assigned, and its choreographed sequences have been refined and honed.

The title has shifted from Cube, which, while literal, did not really capture the range of emotions delivered by this work. I was expecting Body Sculpture to have an eerie, freaky quality, but stepping away from its debut to media, the overwhelming feeling was one of humanity. It is surprising for Wolfson’s work, which has often been criticised for preying on people’s trauma.

Jump to:

A range of emotions, both alarming and heartfelt

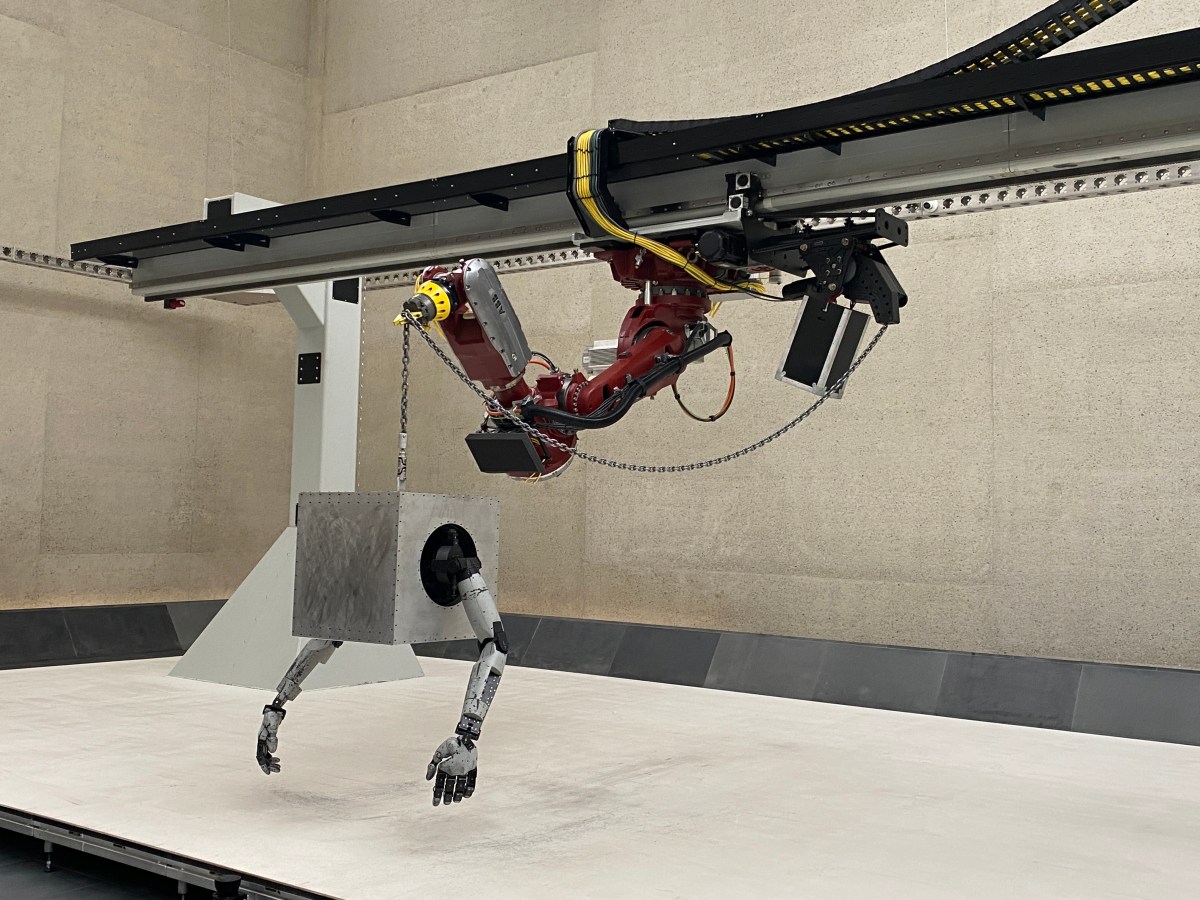

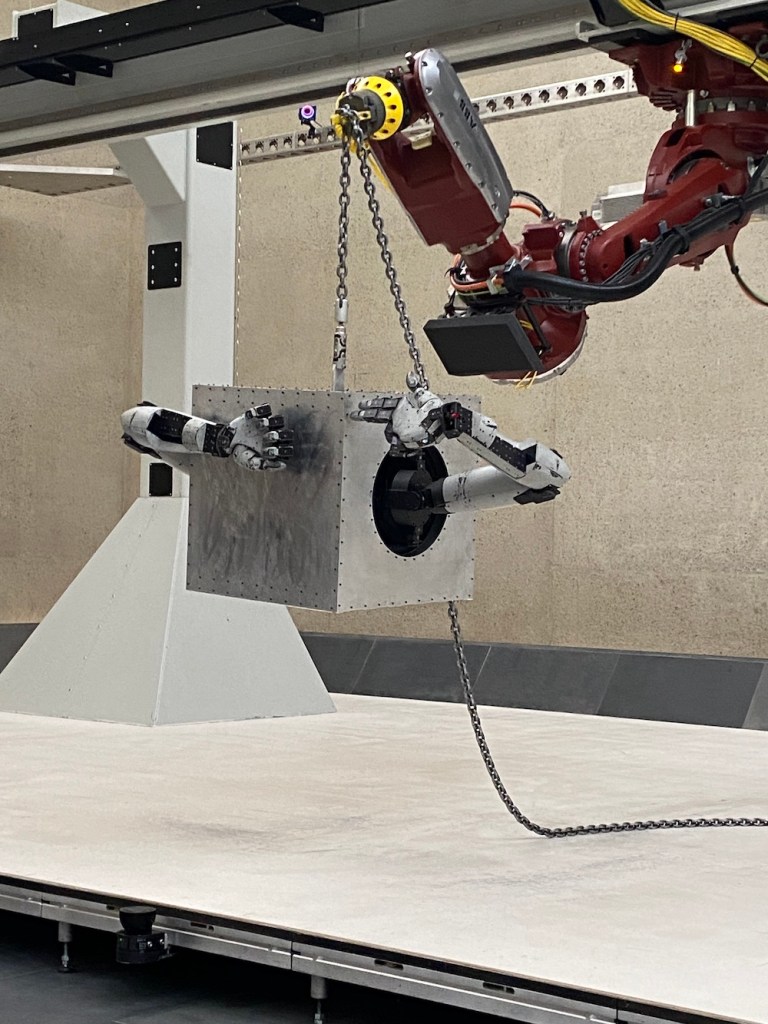

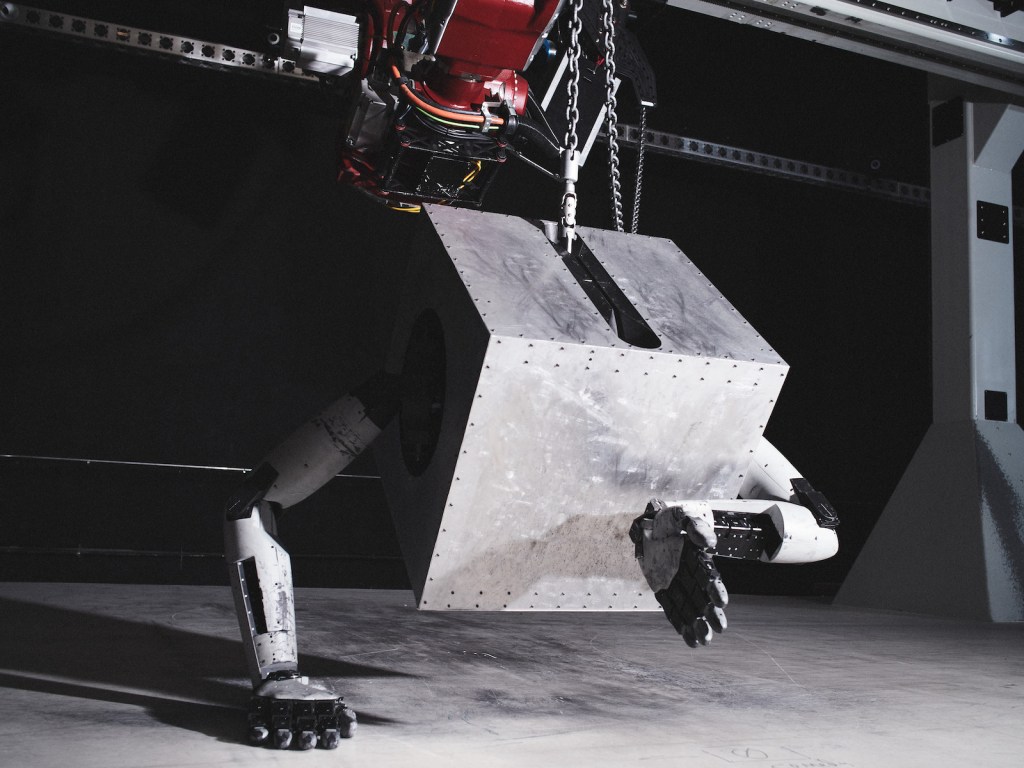

The sculpture is as impressive as its price tag. An enormous mass of aluminium framing – which acts as a proscenium arch, a robust kinetic robotic arm, clanking chain and a central anthropomorphic cube –moves through a sequence of gestures at times sensitive, other times violent, erotic, threatening, enticing, comforting, humble, grandiose.

Visitors sit locked, as if watching a piece of theatre, complete with curtain calls. Wolfson told media that spending time with the sculpture has, ‘made [him] incredibly sad,’ adding that he identifies with both robotic bodies (aka the cube and arm). I should be careful to add, however, that this is not a self-portrait. But is it a portrait of our times?

In a nutshell, as with Wolfson’s previous animatronic works Female Figure (2014) and Colored Sculpture (2016) (both controversial and criticised), this new commission aims to trigger emotional and physical responses in the viewer. Wolfson often places the viewer in a moral dilemma – as a witness to violence, self-harm or abuse. In Body Sculpture the topic of suicide is raised.

The position of the provocateur in art is not entirely new; activist and socially motivated art-making have raised thorny or taboo topics for decades, forcing audiences to consider the darker aspects of the human condition of our contemporary world.

At the work’s unveiling Wolfson said: ‘It’s about seeing ourselves through three‑dimensional objects.’ In describing Wolfson’s work, NGA Director Nick Mitzevich added: ‘You can’t escape thinking about your own body when you watch Body Sculpture.’ He nailed it.

Watching Wolfson’s robotic cube it is at once a torso, a face, a stomach, a head – all shifting under the gestures of the most delicate hands (I understand each has around 100 elements to it). You physically feel connected – and yes, at times, uncomfortable.

The tech stuff

Body Sculpture is the third large-scale installation Wolfson has realised in collaboration with Mark Setrakian, the highly celebrated Los Angeles-based technologist known for his work on Men in Black (1997), How the Grinch Stole Christmas (200) and the Hellboy films, among others. They have worked collaboratively now for over a decade. On this program, they have also brought in Academy Award-winning, Richard Taylor – the co-founder, Creative Director and CEO of the New Zealand studio, Wētā Workshop.

Setrakian has written the program to animate Wolfson’s vision for Body Sculpture, what he described to ArtsHub as a ‘highly adaptable control system’ that can respond to shifts in the cycle of the performed work. This all sits behind a wall in a hidden room in the Gallery, sensors constantly recording and adjusting movements for minuscule corrections.

Sound levels reach 100 decibels at certain points (equivalent to a motorbike) with loud drumming and impact noises.

The half-hour performed work takes its origins from performance art, kinetic art and pivotal moments in art history as reference points – be it a hand gesture from a Renaissance painting or a Donald Judd minimalist cube of polished stainless steel. These are harder for the audience to read or draw connections to, so Wolfson has curated a small exhibition of artworks from the NGA’s Collection leading into the space to add context.

And the performed experience

Visitors walk into the lower temporary exhibition gallery at the NGA and are invited to grab a stool for the 30-minute performance. The room is spare. The first movement is telling. Both hands are raised, similar to the Auslan gesture of silent applause, welcoming viewers. The cube then dips forward in a low bow to the audience. It then grounds its hands. The gestures are very slow at this point, pulling us in sync with its timeframe.

One hand moves and is centred in a gesture of namaste, or a gesture found in many sculptures of Eastern and South Asian nations. Then both hands hug the torso of the cube. These are all theatrical and feel familiar and welcoming. What is surprising is the delicacy of these gestures. They are not clunky or staccato (aka 1970s robot dance movements). The hands have an ape-like quality with giant leathery paws, grooming with gentle love and care. They are primal but also cutting edge.

The next sequence moves to a circular rubbing of the form – it is comforting, it is sensual – momentum builds. Noticeably, an audible aspect of the piece grows as we settle in to reading it visually, and a sense of crescendo is building with a clawing of hands and the cube humping in a sexualised manner. Are we uncomfortable? Is it consensual? Yes, we are talking about a sculpture, but by this point it is 100% an expression of a range of human emotions and relations. We have forgotten ourselves and we are one with this performed moment.

The robotic arm drops a chain that holds the cube aloft, as if discarding it in post-coital satisfaction. The hands persistently drum for attention with a feverish emotion – a finger begging us to come. It is slightly creepy. The drumming on the box has a hypnotic, primal quality – and yet it also nods to the cajón, a percussive instrument you sit on and drum. It feels cross-cultural, beyond culture and benign of culture at the same time.

The robotic arm starts smashing the chain against the armature violently. Is it a rift between lovers or the tantrum of a child? The arms widen in a gesture of submission. We are reminded of a thousand religious images across time and the annals of art history.

The robotic arm lifts the cube again – it dangles, drained of life. Is it submission, exhaustion, peace found or a point of perfect balance found between these? The piece then takes a dark turn – one not all visitors will appreciate and one that will be open to criticism. A hand forms the gesture of a gun and – slowly – positions and shoots, first the side of the head, then the forehead, then the skull. Suicide is perhaps the greatest problem afflicting social harmony globally, and Wolfson aims to confront it.

Read: Mental health for creative people: five tips to thrive

It concludes, throwing wide its arms again in submission, then a hand to the chest and a low bow, hyper theatrical as a diva would conclude an opera.

Mitzevich said the work ‘builds on the sculpture of the 19th and the 20th century’.

‘It builds on the notion of forms. And what it does is pull together a visual language that brings those threads together with a great sense of clarity. It adds to the National Gallery focusing on works of absolute resolution, that are innovative or breakthrough moments,’ he added.

Read: Towards continuum: behind the hardware of digital art

In an interview with the NGA, Wolfson concluded, ‘Body Sculpture is an artwork without a moral position or “new” moral position, in that the previous artworks were trying to express something that wasn’t morally or socially accepted yet. Instead, Body Sculpture suggests that an object can mirror your body and reinsert you into your body, assuming that you are not present in your body.

He continued: ‘I don’t think of what I am doing as provocation, but as art. I find the idea of provocation silly. I’m making the kind of art that I personally like and it’s doing what I think good art does.’

New York-born Wolfson (1980), graduated from the celebrated Rhode Island School of Design in Providence (US) in 2003, followed by a whirlwind career exhibiting across some of the world’s leading art institutions. He currently lives in Los Angeles. This is the first solo presentation of Wolfson’s work in Australia .

Jordan Wolfson: Body Sculpture has been curated by Russell Storer, Head Curator, International Art. You can see it at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra from 9 December – 28 April 2024.

Free, but bookings required.

The writer travelled to Canberra as guest of the National Gallery of Australia.