With ambassadors like actor Steve Martin and his wife Anne Stringfield promoting the collecting of Aboriginal art, it is not surprising that both the museum and commercial gallery sectors in the United States are taking notice.

While the largest exhibition of Aboriginal art to travel to the US has had a bit of a false start – hampered by US Federal Government closures this past month – a number of key commercial exhibitions have targeted international collectors, and with more positive news on the horizon, this trans-Pacific connection continues to grow.

Aboriginal art in America – quick links

US collecting history of Aboriginal Art

Long before Steve Martin and Anne Stringfield started collecting Aboriginal art, collectors John W Kluge and Edward Ruhe were at it. Their initial collection of bark paintings would become the foundation for the Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection at the University of Virginia. That institution is now head up by an Aboriginal curator and artist, the Barkandji woman Nici Cumpston OAM, who was appointed in January this year.

Many in Australia will know Cumpston as the Artist Director of the Tarnanthi Festival of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art, which celebrated its 10th anniversary last month with the exhibition Too Deadly: Ten Years of Tarnanthi.

It was Cumpston’s final edition, and she has now handed over the reins to a new generation of curators as she turns her focus towards a new gallery build at Kluge-Ruhe.

Cumpston tells ArtsHub: ‘When I applied for the position, my interview was really all about what I’ve done here with Tarnanthi, and the collection here at the Gallery, and how to bring an element of Tarnanthi to the US and Kluge-Ruhe.’

‘People flock to us,’ Cumpston adds, describing the 1940s cottage housing the Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection. ‘They love it, because it’s like a little bit of Australia. When you walk in, there’s a beautiful welcome mall that has photographs of artists making their work and quotes, so you get the artist’s voice. We’re an outpost, we’re a real refuge for people.’

Cumpston says that the organisation has been given the go ahead to proceed with plans for a new museum, which has now entered the design phase. ‘We’ve got a major, millions-of-dollars gift, so it’s moving in the right direction. I feel like the future is looking good,’ she tells ArtsHub.

The new gallery will sit within a hub of arts departments at the University of Virginia and will greatly expand the visibility of Aboriginal art. ‘I think it’s 40 times more floor space – and that just leads to more opportunity for Australian artists,’ says Cumpston.

Other collectors who have made a significant impact in the US are Dennis and Debra Scholl, who travelled to Australia’s remote homelands to collect artworks, both ceremonial objects and contemporary paintings. They have made substantial donations to American institutions, such as the Frost Museum in Miami and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Also making an impact is the New York-based couple John and Barbara Wilkerson, who have amassed an important collection, as highlighted in a 2015 exhibition at the Nora Eccles Harrison Museum of Art at Utah State University. And of course, there was Steve Martin’s 2019 Gagosian Gallery exhibition in New York, which pushed the collecting of Aboriginal art into the spotlight.

It is not surprising then, that Australian galleries such as D’Lan Contemporary and Michael Reid have become active to capture this market, with both staging exhibitions in America this past month.

US closures are unfortunate timing for celebration of Aboriginal art

The timing – which was to be brilliant – became bleak, however. These commercial shows were set to coincide with the opening of The Stars We Do Not See: Australian Indigenous Art, the largest ever exhibition of Aboriginal art in the US, at the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC.

Due to open on 18 October, the free exhibition was shut down before it even started, thanks to the US Federal Government shutdown that came into play on 1 October, when Republicans and Democrats failed to agree on a government funding bill for services through October and beyond.

Artsy reports that ‘the event leaves some 40% of the federal workforce – approximately 750,000 people – on unpaid leave,’ adding that ‘the last time the government shut down was in 2018, during Donald Trump’s first term, and it lasted a record 35 days.’

Today, 12 November Australian time, that record has been expanded to 43 days and counting – though an end may be in sight at last, with the US Senate recently passing a short-term government funding bill to be debated by the House some time this week.

Regardless, Washington’s National Gallery closed its doors on 5 October, with its website still stating, ‘all programs would be canceled until further notice’.

Hope for largest Aboriginal exhibition despite shutdowns

With the exhibition several years in the planning, the shutdown of America’s most prestigious art museum was not something Myles Russell-Cook, former Senior Curator of Australian and First Nations Art at National Gallery of Victoria, was expecting. It is almost like a Covid gut-punch all over again.

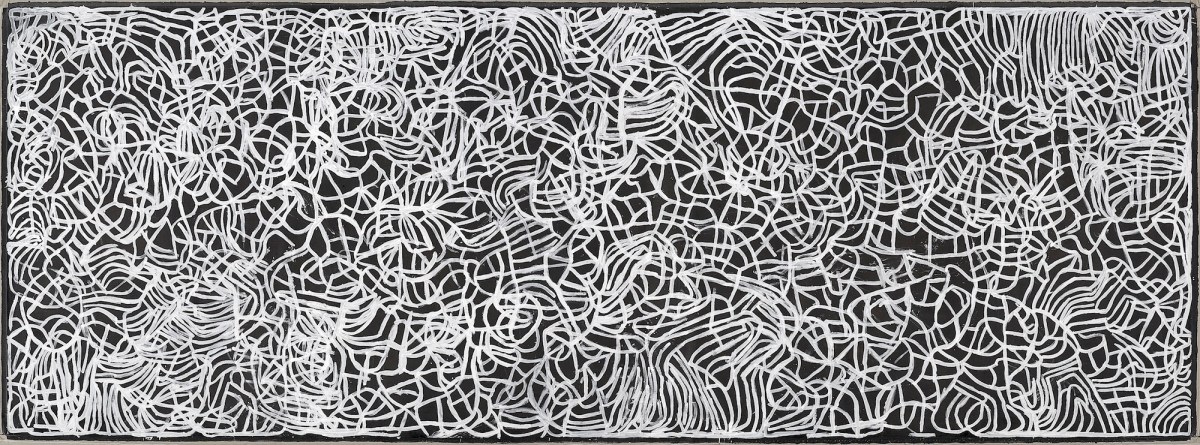

The Stars We Do Not See: Australian Indigenous Art draws together over 200 works by more than 130 artists from the NGV Collection. Many are iconic masterpieces such as Emily Kam Kngwarray’s enormous 1995 work, Anwerlarr Anganenty (Big Yam Dreaming), which measures three by nine metres and has never been seen before in North America.

In a formal statement, the National Gallery of Art writes: ‘Russell-Cook has shaped an exhibition that charts watershed moments in Indigenous art, revealing a rich history that pre-dates the arrival of Europeans and introduces audiences to customary forms and styles in Indigenous Australian art, such as conceptual map paintings of the Central and Western Deserts (colloquially referred to as ‘dot paintings’), ochre bark paintings, ambitious experimental weavings, [and] ground-breaking new media works.’

Answering the US audience’s yearning for deeper learning about Aboriginal art, the exhibition was to be a cementing moment. The Stars We Do Not See: Australian Indigenous Art is slated to continue at the National Gallery through to 1 March 2026, so there is still room for optimism.

And, following its run in Washington DC, the exhibition has been scheduled to travel to the Denver Art Museum in Colorado, the newly refurbished Portland Art Museum in Oregon, the Peabody Essex Museum in Massachusetts, and the Royal Ontario Museum in Canada from 2025 to 2027. Thankfully, these venues remain open at this point in time.

Ambition shared by Australian gallerists showing in the US

Two Australian exhibitions braved the US this October. The first international exhibition by senior Yankunytjatjara man Reggie Uluṟu was presented by D’Lan Contemporary in New York from 2 October to 7 November. A group exhibition was also presented by Michael Reid Sydney + Berlin in Washington DC from 18 October to 10 November.

Welcoming Uluṟu’s show with inma (ceremonial song and dance), a delegation of senior Anangu leaders from Mutitjulu community headed to New York. The gallery also programmed talks and exchange events, and the delegation met with The Hon Kevin Rudd AC, Australia’s Ambassador to the United States and former Prime Minister of Australia.

‘This historic meeting represents a powerful moment in international recognition of Anangu culture, coinciding with the 40th anniversary of the Handback of Uluṟu,’ said a spokesperson from Anangu Communities Foundation, which was established by Voyages Indigenous Tourism Australia to support Anangu-led projects that strengthen education, culture and economic development. ACF were also partners in the exhibition with D’Lan Contemporary.

Reggie Uluṟu played a central role in the 1985 Handback of Uluru to its Traditional Owners, and for many years worked as a ranger in Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park and as a tour guide, sharing his ancestral lore with thousands of visitors.

Opening the following week, Michael Reid Sydney + Berlin invested heavily in presenting the exhibition The Stars Before Us All.

The exhibition title riffed off the blockbuster National Gallery show. It was Reid’s first significant foray into the US market, preceding the opening of a new Los Angeles location, and included the work of 20 leading artists, among them the legendary Emily Kam Kngwarray, this year’s National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Award-winner Gaypalani Wanambi, as well as Owen Yalandja, Djirrirra Wunuŋmurra Yukuwa, Dr Christian Thompson AO, Betty Chimney, and also Cumpston with her hand coloured photographs.

Read: Gaypalani Waṉambi wins the Telstra Art Award at the 2025 Telstra NATSIAA

Joining Director Michael Reid in Washington was Ngan’gikurrungurr woman, senior artist and Cultural Director of Durrmu Arts Aboriginal Corporation, Regina Pilawuk Wilson – her first opportunity to visit the room named in her honour at the Australian Embassy to the United States.

For both gallerists, the role of soft diplomacy was an important catalyst for ensuring future cultural activity.

Reid said at the time: ‘This is a watershed moment for Australian First Nations artists globally and our exhibition [The Stars Before Us All] invites US collectors to discover a diverse collection of works by some of the most essential voices in Australian art.’

He added: ‘The Stars Before Us All is an exhibition that opens a window into an extraordinary contemporary art tradition. It reveals a culture that, after millennia of relative isolation, has in the last two decades burst onto the global stage, offering audiences not only works of great aesthetic power but also a vision of art as continuity, survival, renewal and growth.’

A love affair standing the test of time (and politics)

Cumpston tells ArtsHub that things are ‘in a difficult state, with museums closing’, but like Reid and D’Lan, she remains optimistic for the future.

The new Kluge-Ruhe gallery will be right downtown in Charlottesville, ensuring the visibility of Aboriginal artists in the cultural fabric of the city. ‘It’s on the grounds of the University, which means we’ll have the foot traffic from the art school, from all of the different departments, and it’ll be a hub. At the moment, we’re about 12 minutes from the center of Charlottesville but it [may as well] be 112 minutes.’

Cumpston says the Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection currently has six interns, four full-time staff and two part-time staff all working towards curatorial and research programming focused on Aboriginal art.

This support network – and the close relationship of Kluge-Ruhe with the Art Gallery of South Australia – made it possible for Cumpston to work across borders and deliver Tarnanthi this year. It is indicative of a level of collaboration that can only grow as more Australian-led activity is based State-side.

She adds: ‘I really feel like that’s made a big difference, as well as those touring shows that we’ve done with Tarnanthi internationally, and of course the tour of the Kuḻaṯa Tjuṯa installation of many spears, which we went to seven venues throughout the US with another work from our collection about Maralinga [over 2021 to 2023].’

The installation was part of the exhibition Exposure: Native Art and Political Ecology, which documented the responses of First Nations artists around the world to the impacts of nuclear testing and mining on their land.

Cumpston adds: ‘One of the main things we did when we first started Tarnanthi was to make friends across the city and state, and to engage with other organisations to exhibit First Nations art – and that was a really big priority in the beginning.’

She tells ArtsHub that the hand-holding has grown to a point where both partner venues and artists have become ambitious themselves.

‘We have 25 partner exhibitions this year, and people come to us now with their artists and their ideas, as opposed to us trying to find people to match. Then also, the last two Tarnanthi [have] had a regional curator. So, we’re enabling artists from not only country or regional South Australia, but for other emerging artists to be part of the story, which is something that I’ve always felt really was so important.’

This year’s edition of Tarnanthi, the exhibition Too Deadly: Ten years of Tarnanthi, will tour for the next two and a half years.

Cumpston says of the future: ‘I think there’s more confidence. I think what I really want to see is more and more institutions looking to people who haven’t had that opportunity yet. Let go of the worry – just believe in the artist.

‘Someone asked me the other day, “How many cups of tea have you had?” and that’s the thing – it’s just about sitting down, taking time with people. So that’s what I absolutely hope will continue, that it’s not just selecting work for exhibition; it’s not just about the same old people getting the gigs and international opportunities. Hopefully some of those people are bringing others along on their journey,’ she concludes.

Clearly, Cumpston lives her own words by creating pathways for artists in the US.