Award-winning Australian craftsman, Damien Wright, delivered a keynote at the recent Making it Craft Symposium, hosted by Craft VIC.

Known for his blend of Australian timbers, organic finishes and contemporary design, Wright says that during his working life, ‘craft has gone from a dirty word to a symbol of sustainability, connectedness and authenticity.’

While we have seen a boom in various craft genres in recent years, in particular ceramics and a resurgence of textile art, 2020 has also brought makers into the spotlight, their practice more conducive to social distancing, home studios and the hyperlocal during the pandemic.

Read: COVID-19 has been a boon for crafts

Wright said: ‘Neo liberalism divides production globally, where everyone is a procurer; Covid has showed the insecurity of that [model], and it has provided an opportunity for the micro business.’

He continued: ‘What the pandemic has done is thrown a massive challenge to capitalist society about how they are going to organise their material culture. I think we stand a very good chance of presenting ourselves, as craftspeople, as a really valuable part of a new economy – an economy that is local – not just local materials, but local culturally, looking at what this place means through materials and practice.’

What a career in craft might mean today

Wright works largely on a commission basis to create furniture and sculptures, often in consultation with architects and designers.

He says that, ‘what you make, and how you make it, must say something about you and our culture.’ He works with Australian timbers.

‘The idea of a craft business (that is very much in inverted commas) is both obvious, in that it has to be a [viable] business, but it is also this model of a working life that doesn’t fit well into a business model.’

‘What you make, and how you make it, must say something about you and our culture.’

– Damien Wright.

Wright describes what he does as entirely reliant on making things and selling them. So how does he get the selling part right?

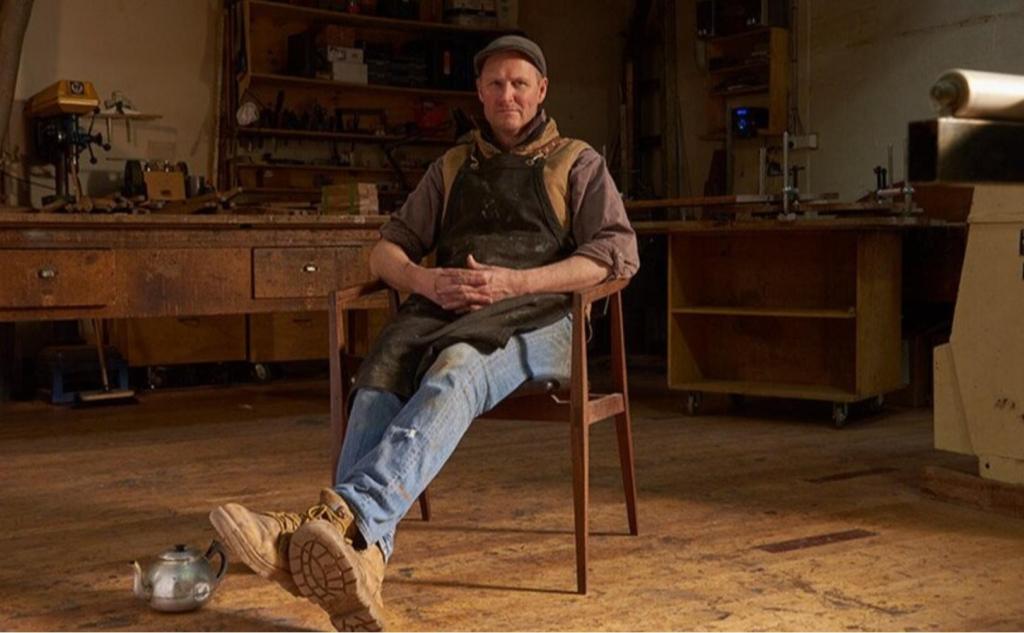

He said that to survive you have to be all things to all people, moving easily from your workshop scrubs to ‘flash shop clothes’. ‘We are prone to descend into our own making universe, but you have to go out into the world and present yourself and make connections to have a sustainable craft business.’

Swapping studio for business attire, Damien Wright says you have to get out there as part of the job. Photo screenshot Making it Craft Symposium.

What it means to be a success as a craft business

Wright calls what he does a ‘petty capitalist craft business’, which essentially means he doesn’t get paid unless wood goes out the door.

He has run his Northcote studio for 25 years. ‘I would like to think my longevity suggests I am successful,’ he said, but added that he has come to that in a round-about way.

‘To set up a craft practice, and to think of it is a business, you have to own up to the structural nature of what you can achieve. It took me a long time to sort this out. It would have been better if I had done it earlier,’ said Wright.

He was talking about recognising the difference between what you think is important, and what clients think is important and sells.

‘I have always privileged what I wanted to do. But you get to a point in your life when you realise you have dedicated your life to a practice and you are not going to get paid for it the way you would in another profession, and that can destroy a lot of artist and craftspeople. It is a very vexed concept,’ Wright explained.

He said the alternative to a craft business is a vocation. ‘Think through a vocational lens; that is you are doing it because you want to do it – it’s part of you – and you want to try to separate yourself from the position of capitalism.’

‘You want to value what you do as a maker – that is what I call a success,’ Wright added.

‘If you take a capitalist logic to craft you are in big trouble. You want to value what you do as a maker – that is what I call a success.’

– Damien Wright.

After studying art and politics, Wright graduated into the last recession with scant chance of a job. So he started making furniture.

‘That was first time I through about craft; I didn’t really understand it as a career,’ he said. ‘But I realised in my early 20s that I wanted to be really good at it. I spent the next 20 years in a bunker working to establish a business. I turned my back on a more bourgeois or managerial life. And I just built it, and built it.’

Wright believes his arts degree was critical to his business success because it gave him critical thinking.

‘Critical thinking is what matters because it is ‘the why’. The world of broadcasting has allowed us to pump out ‘the how’ – anyone can learn the how. The mystery is why. If you can do that, then the audience for your work will expand.’

Compartmentalising your practice

Wright said the key to a craft business model is to understand the various marketplaces for your work.

‘I only got my head around it the last couple of years – it is important to understand – to see your work engage in a multiplicity of marketplaces.’

Wright is talking about the mental separation of commission work, production work and exhibition work, ‘and apportion time and resources to each of them.’

‘Exhibitions costs you money. [They] don’t stand up to the scrutiny of small business, but they connect you to a marketplace that adds value to your work. If you reject that, it is a long way back. My advice is to continue exhibiting,’ he said.

Wright rejected the commercial gallery sector for most of his career – saying he had an epiphany at one of his exhibitions looking around the room and realising that no one was going to buy anything.

He only returned to showing in the past two years. He said it is sound practice to build into your business structure an exhibition platform that doesn’t rely on selling, keeping your ‘craft business’ streamlined to the side.

Make no illusions – craft is a tough business

‘I ask people to persevere. If you are 51 [like me] and have an established practice then people respect what you do. That is different to a 31-year old trying to find their price point. It is a bit of retail, bit of gig economy, and that is hard.’

He continued: ‘But if you can survive through this moment, the new economy will be more local and will want you.’

Wright believes that a future in craft business also lies in collaboration with Indigenous makers. ‘Crafts people and Indigenous people will be able to find a way of talking about being in this country through materials …Craft is permeable frontier, and a way to de-polarise this country and find a language overlap through is through craft collaborations.

‘That is really exciting and really vibrant, and we have to grab these moments,’ said Wright. ‘We need to establish ourselves as a country who can look at material making, and how it is used as part of our complicated understand of who we are. [This is critical] to craft – and where we are now as an industry – and what that might mean in the next period of our careers and output.’

Read: Making craft a national agenda

Wright acknowledges that the craft sector has had to struggle to be valued and heard. ‘We have had to reframe ourselves as designers – I am a designer and a maker – but I very much feel the weight of the industry has moved behind design, and craft is seen as part of broader procurement platform for design. I object to that profoundly.’

‘Craft is not one of the many choices that design can have,’ he continued. ‘Craft is of itself a thing that humans do, and organisations [need to] see that and represent us and collect us,.’

‘Your future and our future is in the handmade.’

– Damien Wright.

Wright’s thinking is that our arts organisations are, ‘blind for a number of reasons: they struggle with someone who has both an intellectual life and a manual life. These are not new arguments, they were had in the 70s… We need to maintain the identity of craft.’

So, his advice is, ‘you need to get up earlier than anyone else; you need to work harder than everyone else. It is so good to see what you make and think, “fuck I made that”, and that papers over all the indignities – maybe that is just pure vanity – but what you have to honour is that you want to make stuff and your future and our future is in the handmade.’

The Making it Craft digital symposium was presented by Craft VIC, February 2020.