Max Gillies returns to the stage to present three short works by modernist masters from across the theatrical canon: Anton Chekhov, Samuel Beckett and Jack Hibberd at Melbourne’s fortyfivedownstairs.

Taking its name from the Beckett classic Endgame, the three works are connected by their exploration of mortality and the absurd.

Gillies is well known as a comedian (from the 1980s onwards, his satirical portrayals of our Prime Ministers and other Australian politicians were a television staple for years); he was also a founding member of the experimental theatre collective the Australian Performing Group (APG), which brought early Hibberd works (such as Dimboola) to the stage for the first time at La Mama Theatre and its neighbouring venue, the now-legendary Pram Factory, in the late Sixties and throughout Seventies. Gillies himself won a Theatre Australia award in 1977 for his performance in Hibberd’s A Stretch of the Imagination (1971).

In Endgames, Gillies brings us an excerpt from this Hibberd play, performed nearly completely off-stage, as a theatre work of sound designed by Darius Kedros.

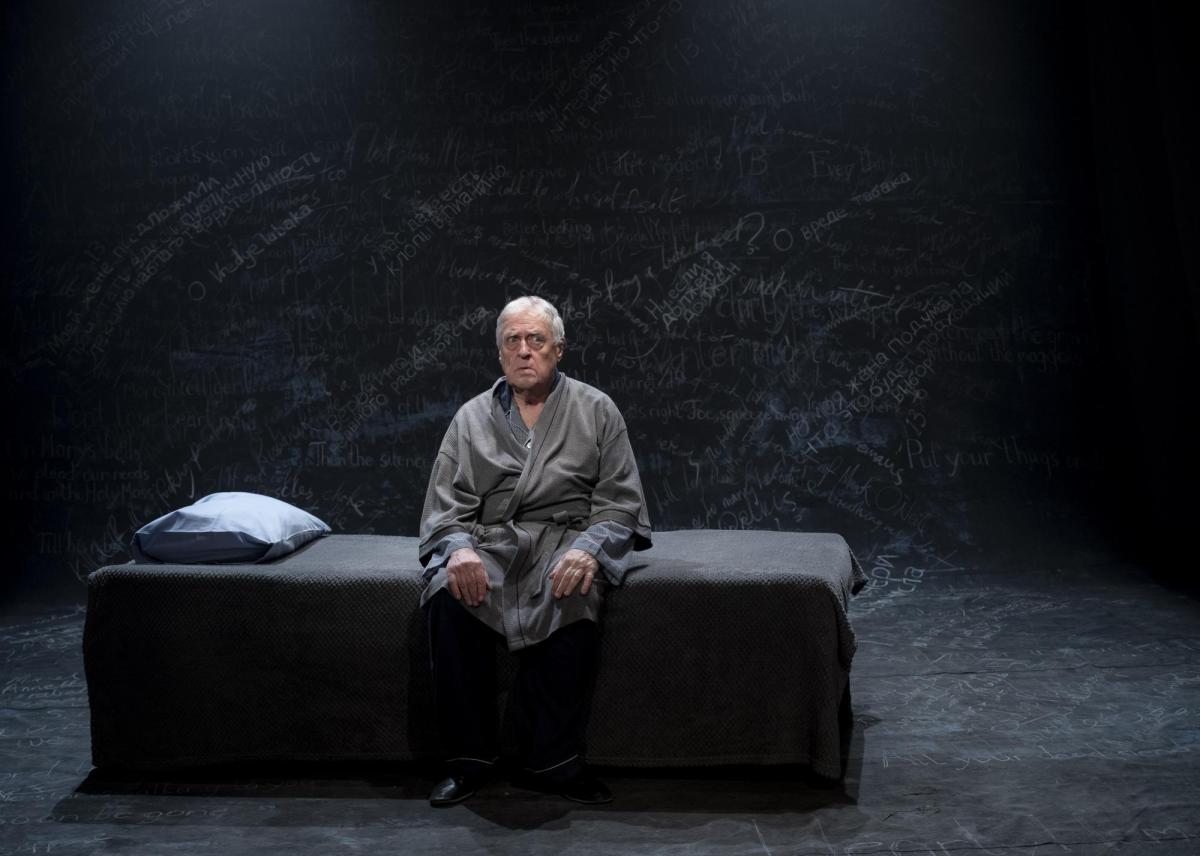

Fortyfivedownstairs’ large and ever-adaptive warehouse space has been shortened, with one single seating bank facing the entrance and a curtained-off bar. Two of the large, white-framed windows in the red-brick wall adjoining the stage have been kept uncovered, while the technical desk and operator are placed visibly at the side of the stage. A long width of black scenery roll extends from the roof at the centre-back of stage to the front downstage, marked with graffiti-like scrawls in various languages, written in white chalk. What looks like a bed – or a coffin – lies at the stage’s centre. The result is a set that thoughtfully engages with the history of the theatre itself – while visibly heroing the technical production, so much a part of the realisation of these works.

Close mics – likely a pre-record – pick up Monk O’Neill’s wet snore, his (very) drawn-out morning urination as he boasts to himself about his penis size, his clambering noisily around his house, equally self-aggrandising and drawn into fits of existential ennui as he contemplates his own death. The only time we see Gillies in this extract of A Stretch of the Imagination is when O’Neill runs out of his house onto the dimly lit stage with a rifle to confront an expected intruder, which he finds to be merely an emu, before he heads back inside (off-stage) again.

A Stretch of the Imagination was adapted as a radio play for the BBC in 1975 and this performance feels like a mix between live radio play and theatre. The five-point surround sound and complex sound mixing brings O’Neill to life, positioning him clearly in space: every rasp, dribble, shout and groan crystal clear, the movement and echo of his footsteps painting a picture of the expanded space around him and the rustle of breeze and birdsong evoking the outback outside. It’s really theatrical sound design at its best.

The second piece is Beckett’s Eh Joe (1965). Originally written for television, Gillies performs this piece on stage, without many of the highly specific technical and stage and camera directions demanded by Beckett. Gillies as Joe walks slowly on stage, shuffles around in his grey dressing gown and slippers, before seating himself on the middle of a simply-made grey bed. We hear the voice of a woman, which seems to come from inside Joe’s mind. As the voice spits out accusations, viscerally depicting the impact of his selfish deeds on all around him, including the multiple suicide attempts of a young woman he has spurned, Joe sits in fearful paralysis.

Whatever your views on Beckett’s rigid (and – by his estate – still litigiously protected) directions, here the lack of a close-up camera on Joe turns the piece into a protacted scene of a frighted-looking man on a bed.

The (again) excellent sound design and recorded audio performance by Jillian Murray (and a later close-up of Gilles’ eyes, which appear projected onto the stage backdrop above Joe) does enliven the scene, but – unless you’re right in front of Gillies – you’re mostly left out of the nuances of his own tortured guilt, as you simply can’t see his face in close enough detail.

While the focus shift away from the chauvinistic protagonist Joe towards his female accuser makes sense to a modern audience, it also jars slightly, given that the only live actor in the scene is Gillies – it feels like he’s underused, dramatically, as a consequence.

The third and final piece is Chekhov’s one-act play, On the Harmfulness of Tobacco (1886). For this piece, a stage riser replaces the bed on the stage, with a podium at its centre.

While the Hibberd excerpt is a masterclass in theatrical sound design with a largely physically absent Gillies, and the Beckett presents a restrained and silent Gillies, the Chekhov brings the celebrated actor downstage, into the light – and gives him some lines.

Gillies becomes the buffoonish Nyukhin, here to present a lecture on a topic that he himself (as a smoker) does not agree with, because his wife has told him it would be suitable material to present.

On opening night, it was difficult at first to work out whether Gillies’ seeming lapses (and a few side-stage prompts) were part of the play, as Gillies was firmly in character throughout.

The paper-shuffling amateur academic (Nyukkin informs us he never had time for university degrees) becomes less a pontificating pedagogue and more an absent-minded clown, losing his place in his papers and abandoning the topic of his lecture to complain to his audience about his wife and what he sees as her needling demands of him.

As a trio of works, there is a lot, theatrically, to enjoy about Endgames, which is a tour of modernist male characters forced to reckon with their own decline and looming mortality, performed by a celebrated octogenarian actor who has been a pioneering force in modern Australian theatre over decades.

Read: Theatre review: FEMME PLAY [ungrateful slut], The Butterfly Club

But fans of Gillies from his satirical political skits (like my neighbour – who didn’t return to his seat after interval) be warned: this is not just the Gillies show, but a theatrical composition of works attempting to reckon with ideas of theatre itself, explored by these modernists and presented here as provocations.

A one-man show where the one man is barely present for two-thirds of the show isn’t the usual recipe for popular theatre – but one that may present some thought-provoking fodder for theatre-lovers interested in engaging with the modern legacy of some of our modernist masters.

Endgames

fortyfivedownstairs, Melbourne

Director: Laurence Strangio

Sound Designer: Darius Kedros

Lighting Designer: Richard Vabre

Set and Costume Designer: Jason Lehane

Videographer: Milo Strangio

Stage Manager: Shane Grant

Assistant Stage Manager: Sunday Bowes

Performer: Max Gillies

Guest Artist: Jillian Murray

Tickets: $39-$59

Endgames will be performed until 1 June 2025.