Yhonnie Scarce: The Light of Day at the Art Gallery of Western Australia (AGWA) is a moving and, at times, mesmerising exhibition, which reflects on the artist’s ties to her ancestors and her quiet determination to show their stories in full light.

Spread across three gallery spaces and two levels, it is the largest array of works by Scarce – a Kokatha and Nukunu artist – to be exhibited to date.

But instead of feeling overcrowded with ideas, this show provides ample space to contemplate the artist’s beautiful glass forms, while also allowing the stories of past and present lives embedded within them to emerge.

‘The most complex installation process ever’

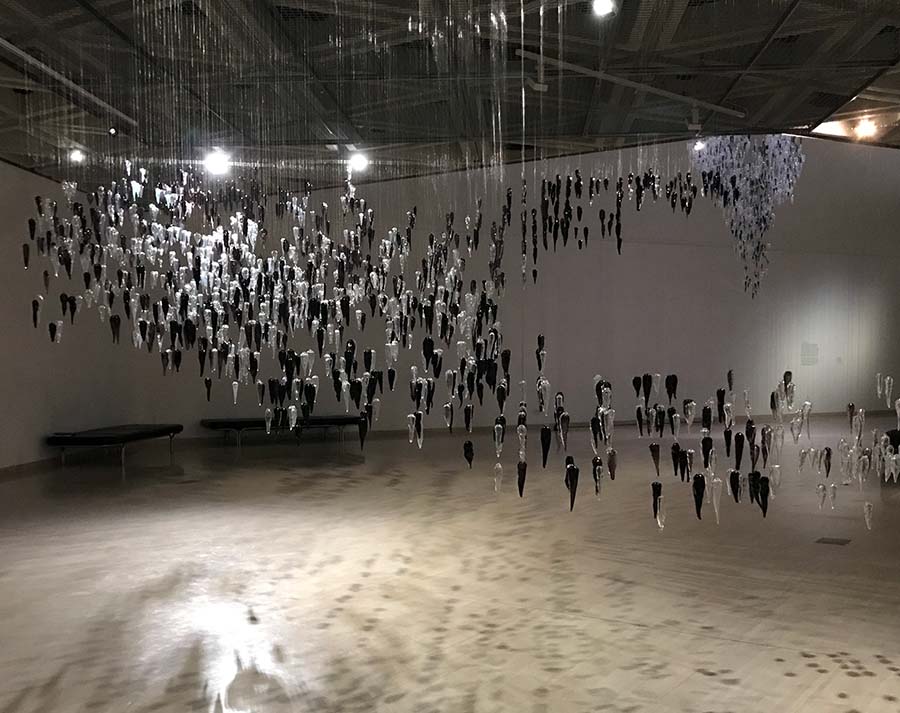

Curated by AGWA’s outgoing Curator and Head of Indigenous Programs, Clothilde Bullen, the show’s final form is the result of a painstaking two-month installation process, which required the meticulous positioning of thousands of the artist’s individual glass pieces to create her monumental – often spellbinding – hanging installations.

As Bullen explains, it is the most complex installation process she has ever been involved in. ‘No one has ever shown all three of these “cloud series” works in the same exhibition, and now we know why,’ she laughs. Each glass work was mounted using a ceiling grid system, with often hundreds of elements suspended.

It is also perhaps the defining difference with Scarce’s major exhibition Missile Park, presented by Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA) in 2021, and curated by a curatorium. The connection that Bullen and Scarce have – that deep one-on-one in navigating difficult subjects – is felt by the viewer.

Ultimately, the curator says she is ‘so glad’ AGWA undertook the difficult task of presenting this many of Scarce’s large-scale installations – a decision that visitors will also appreciate, as they are among the exhibition’s highlights.

Entitled Death Zephyr (2016), Thunder Raining Poison (2016) and Cloud Chamber (2020), these giant hanging cloud works are abstract representations of real-life events, conjuring the radiation clouds that spread across the Maralinga desert in the 1950s and 60s when the British government conducted nuclear weaponry testing there.

At the time, the Maralinga desert was considered an “empty zone” by the British and Australian governments, but it had in fact been inhabited by Indigenous peoples for thousands of years, and many Aboriginal people fell sick or died due to the toxic radiation that spread across the area as a result of the nuclear activity.

Scarce’s portrayals of this history are among the most spectacular by any artist to date, and sit alongside works like Lin Onus’ Maralinga (1990) – which is part of AGWA’s permanent collection – and Lynette Wallworth’s VR work Collisions (2016) in excavating this dark past.

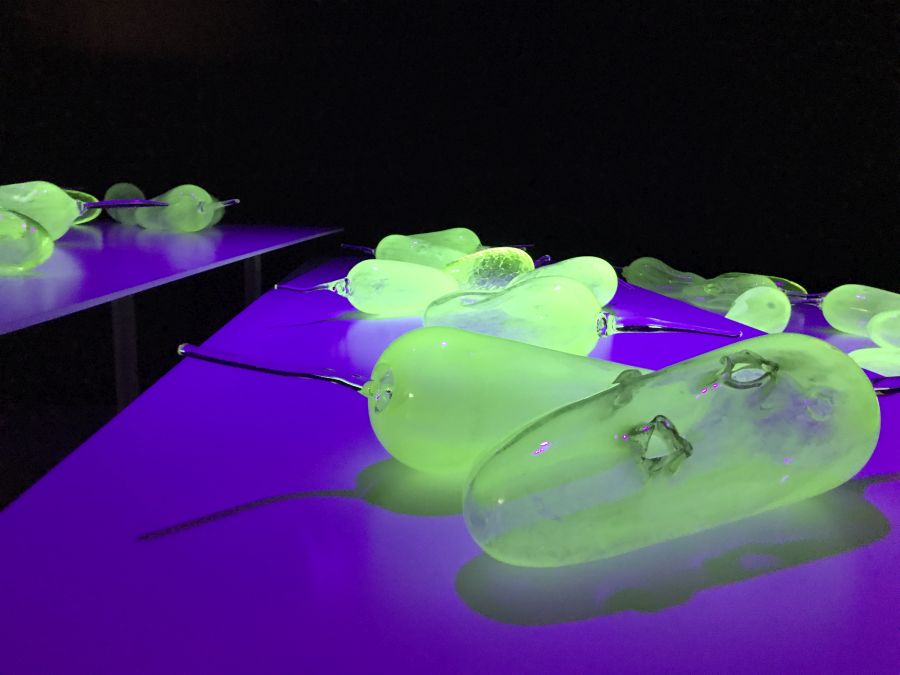

Evidently, Scarce’s interest in Maralinga forms a strong through line in the show. Aside from her hanging glass works, in Gallery 6 her piece Hollowing Earth (2017) comprises a series of hot-formed uranium glass elements that – when viewed under UV blacklight in the small, specially enclosed space – emit an eerie green glow that alludes to the impact nuclear “forever chemicals” have on nature and human life.

Then, in another (more brightly lit) corner of the gallery, Scarce’s 2016 installation Fallout Babies comprises a cluster of 1950s hospital trolleys that were once used as cribs for newborn babies. In each metal tray, the artist has placed delicate white, frosted-glass bush plum sculptures in reference to new life.

Yet this scene is ultimately overshadowed by death, with a backdrop showing the grave sites of the stillborn babies whose mothers were poisoned by the radiation fallout in and around Maralinga.

Unlike some of Scarce’s works, which play with tensions between opposing forces to evoke their meaning, this piece is a cold, hard look at the past and some of the difficult truths that lie there.

Smaller works not to be overlooked

While the exhibition’s larger works are impressive in scale and scope, surprisingly, some of this show’s most interesting parts can be found in the artist’s smaller, more intimate works. A highlight in this regard is Oppression, Repression (Family Portrait) (2004), a mixed-media and glass work created while Scarce was still at arts school.

Installed behind glass in a museum-like display are a series of eight small glass jam jars, replete with tightly screwed-on scratchy tin lids. Inside each one the artist has placed black and white printed photographs of different generations of her family, and on top of their sealed lids are uniquely formed hand-blown glass sculptures resembling various Aboriginal bush foods.

In an artist-led tour of the exhibition, Scarce describes this series in very personal terms. ‘[This piece] looks at how I was at the time, and how I still am, unfortunately, not considered black enough because of my fair skin and blue eyes,’ she says. ‘This work is really about the containment and categorisation of Aboriginal people.’

Among other ideas, Oppression, Repression (Family Portrait) references moments from the past when Aboriginal people were subject to the kind of scrutiny that, while normalised at the time, was deeply disrespectful, exploitative and a symptom of a profoundly racist system.

What marks this work out from many others, is that it speaks to these broad societal wrongs, while also revealing the more invisible, individual hurts still being carried by many Aboriginal people today.

Read: Exhibition review: Nicholas Burridge: Built Geologies, Canberra Glassworks

Subtle curatorial choices support key concepts

The final defining feature of this show is its curatorial direction, which encourages deeper critical engagement with Scarce’s most powerful ideas.

Bullen explains her decision to place a series of large semi-opaque wooden panels around several key works reflects a deliberate choice to create framing devices through which viewers could see, ‘but not really get the full picture [of the works]’.

These wooden structures are especially effective in presenting the artist’s installation Remember Royalty (2020) – a piece acquired by the Tate UK in 2022, and a work with a strong presence in the exhibition’s main space.

Comprising a series of giant photographic portraits of Scarce’s ancestors, its enclosure within its shadowy wooden panel hints at boundaries (both physical and metaphorical) that separated these Aboriginal people from their Country and the wider world during their life on a mission.

Placed around several other important works throughout The Light of Day, these half-lit barriers provide added reason to pause over some of Scarce’s most incisive ideas.

While there is an almost overwhelming amount to take in in this show, ultimately the artist and curator have provided sufficient space to contemplate its weighty themes, and allow us to feel awestruck by this artist’s capacities in the medium that, even after her remarkable 20-year career, continue to drive her practice forward.

Yhonnie Scarce: The Light of Day

Curator: Clothilde Bullen

Art Gallery of Western Australia, in partnership with Perth Festival.

Runs until 19 May 2024.