Know My Name: Making it Modern is the third instalment of an exhibition run by the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) to platform the work of Australian female artists. The NGA’s website explains the purpose of the series: ‘A celebration, a commitment and a call to action, Know My Name is a gender equity initiative of the National Gallery of Australia. Know My Name celebrates the work of all women artists with an aim to enhance understanding of their contribution to Australia’s cultural life.’

This time, the exhibition celebrates ‘pioneering women artists who changed the course of modern art in Australia’.

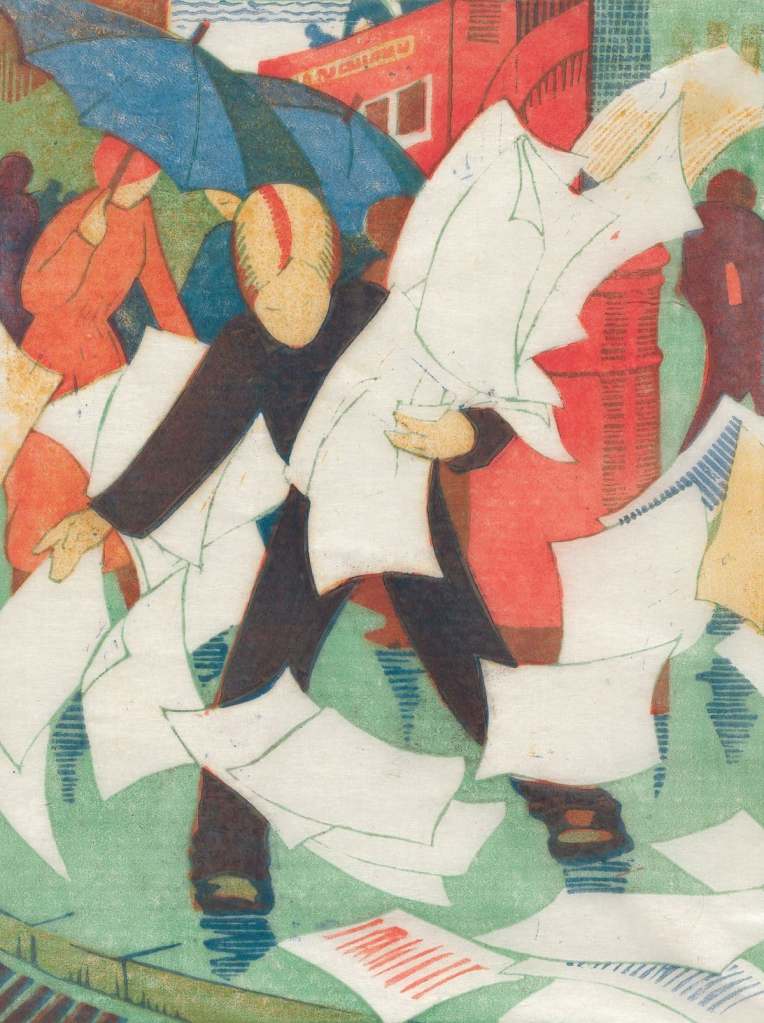

Visitors begin their journey with the work of Ethel Spowers and Eveline Syme – female artists who resisted classical training traditionally offered by academic establishments but, more importantly, were two friends and the daughters of rival media families. Their dynamic experimentation with lino and woodcut techniques are a must-see, framing themes of childhood, travel and urban life.

For example, Spowers’ interest in childhood can be seen through some of her last works, such as authoring and illustrating children’s books including Cuthbert and the Dogs (1948). As in many of her paintings, she utilises elements of fairy tales to bring a magical quality to her work. While the book was produced for children, it’s hard not be charmed even as an adult.

The exhibition then delves into the works of Margaret Preston – the bold and energetic colours in her depictions of nature reinvigorate the still life genre, highlighting a new approach to modernism in Australia during the 1920s and 1930s.

Next is Clarice Beckett, whose work encompasses a combination of both the natural environment and, as the exhibition guide describes, the ‘simple pleasures of suburbia’. Beckett is noted as one of the most original Australia artists of the early 20th century.

Olive Cotton follows, representing a slightly different genre of work – the work of the camera. Cotton is known for images that highlight the immersive qualities of photography. Most notably, her piece The Shell is an illustration of how Cotton may have drawn on her own mathematics degree and familial background in geology to convey through photography new, abstract ways of seeing space and temporality.

Finally, and a highlight for this reviewer, are works by Grace Cossington Smith. Her paintings, informed by a keen interest in European and British Post-Impressionism, beautifully capture the colours of the comfortable domestic and the exotic unknown – bringing them together in artistic and poetic harmony.

This exhibition may have been enhanced by the work of First Nations women artists during this period – specifically in reference to Indigenous modernism, which illustrates the unique development of the artistic experience of First Nations creatives over the early 20th century. Indigenous art theory is a subject that has only recently been brought to the table; it was only during the 1960s and 1970s that a distinction was even made between modern or contemporary Indigenous art forms and traditional Indigenous illustrations. Thus, it is even more critical to explore the work of First Nations creatives in tandem with other artists of the time.

While Know My Name’s first and second instalments, Know My Name: Australian Women Artists 1900 to Now (Parts One and Two) included First Nations women artists, it is important that this thread continues. Rather than exhibiting works by First Nations artists purely in relation to their Indigenous heritage and among other Indigenous creatives, these artists should not be left out of exhibitions such as Know My Name: Making it Modern in order to highlight their achievements as modernist painters in their own right, alongside the likes of Preston and Cossington Smith. It’s important not to box people in one category based solely on racial identity. It would have been refreshing to see the works of artists such as Emily Kame Kngwarreye, for example, whose paintings expand beyond her clan codes, creating new abstractions of ceremonial markings and imagery of her Country’s flora and fauna.

Read: Exhibition Review: Know My Name, National Gallery of Australia

Overall, however, this exhibition is a beautiful encapsulation of the way women artists of the modernist era in Australia powerfully resisted traditional artistic conventions to cultivate new ways of seeing and feeling. The works’ occupations with various themes highlight the diversity of these female artists, and how their brush or lens was never limited to one subject, but the intersection of many.

It was mentioned to this reviewer at the gallery shop that former students of the female artists on display frequently visit the exhibition, a true stamp of approval for Know My Name: Making it Modern.

Know My Name: Making it Modern is on view at the National Gallery of Australia (NGA), Canberra until 8 October; free.

This review is published under the Amplify Collective, an initiative supported by The Walkley Foundation and made possible through funding from the Meta Australian News Fund.