The latest exhibition in RMIT Gallery is a celebration of the work of two men who are hardly household names, Anatol Josepho and Alan Adler. However, if you’ve ever walked around Melbourne’s Flinders Street Station, you’ve seen what both of them gave to the world.

Josepho was a Russian who immigrated to the US in the early 20th century and there invented the Photomation: the world’s first automated, coin-operated photo booth. This was released in New York in 1926 and, upon its success, he was paid $1 million for the patent, equivalent to roughly $18.5 million today. Shortly after, his invention began to enter other countries – including Australia, with one arriving at Myer’s Melbourne store in 1929.

Adler entered the photo booth’s story much later, buying two of them in Melbourne in 1972 as a business opportunity advertised in the newspaper. He may have begun this as a simple business, but, wittingly or otherwise, he turned his machine at Flinders Street Station into a multigenerational, multicultural legacy by self-servicing the machine there for 50 years.

Over that time, he saw trends come and go – cultural, social and technological – but his dedication to his machine persevered, even when replacement parts became impossible to find and he needed to ad lib a repair or two, not to mention when colour and then digital photography steamrolled over his business.

RMIT’s exhibition is a celebration of the technology itself and its cultural impact over the decades and also Alder’s life. “As far as I know”, he says in a documentary-style video in the gallery, “I’m the oldest [and longest-serving] photo booth technician in the world.”

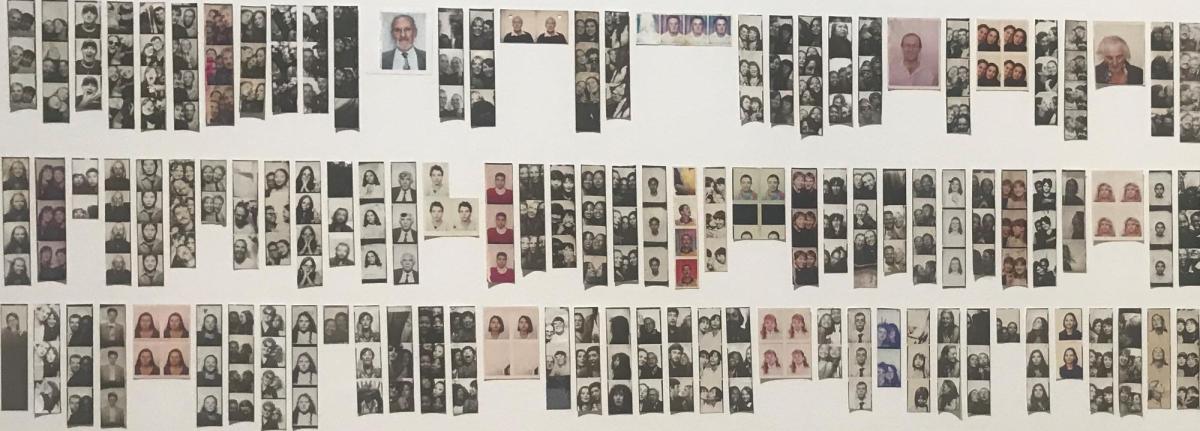

The show is divided into a few distinct sections, such as the photo booth’s introduction into society, its various heydays in both the US and Australia, its use by celebrities such as Marilyn Monroe and Andy Warhol and its appearance in films (it was an important plot device in 2001’s Amélie). Japan’s version of photo booths, purikura, is mentioned, but its roots and social functions are very different to conventional photo booths.

One section gives cross-section schematics of a photo booth, along with a cutaway version of one, where you can see the photo developing technology in action. And, of course, centre stage, is a photo booth itself in all its glory, usually with a queue of people waiting to use it.

A nearby room is dedicated solely to Alder, with dozens of photos of him, which seems a bit self-indulgent until their purpose becomes known – they are all ‘test’ photos, when he was making sure the machine was working again, done after every repair over the past 50 years, making him, according to both the exhibition’s promotional material and the Centre for Contemporary Photography’s 2024 book on Alder, “the nation’s most photographed man”. This book is a companion piece to the exhibition.

Alder’s dedication to his machines has transcended cultural and technological boundaries, which can be read about in this ABC News article celebrating his legacy. It notes that his Flinders Street photo booth now appears in TikTok’s ‘things to do in Melbourne’ lists in various languages and that “for a lot of people in Asia, Indonesia, Korea, until recently so many parts of the world, no one’s ever seen [a photo booth] before”, and so tourists now regularly head there.

The article also highlights the appeal of black and white photos as opposed to colour, and the tangibility of a photo you can hold, especially for people raised in the digital age. It notes that photos you can touch used to be the norm, but are now “a very rare thing”. Quite possibly the appeal of this tangibility, this notion of holding a moment just shared with someone, is still what separates analogue from digital and probably always will; presumably Alder knew this well.

Read: Exhibition review: Writers Revealed, HOTA

Melbourne remains home to a few photo booths, for instance at Flinders Street Station and also in the John Curtin Hotel pub, and in Lygon Court, both in Carlton.

Auto-Photo: A Life in Portraits will be exhibited until 16 August 2025 at RMIT Gallery; free entry.