Every now and again you see an exhibition that totally alters your perspective on things. And when it comes, it is palpable.

That is the impact that British artist Cornelia Parker’s self-titled exhibition has on audiences. Regardless of whether you are an aficionado of contemporary art, or a gardener standing in awe in front of Parker’s exploded shed of garden tools, this exhibition – to use a cliché – captures the imagination of everyone.

She has been described as ‘an artist who blends alchemical transformation with Dadaist absurdity’.

Curated by the indomitable Rachel Kent, MCA’s Chief Curator, these two creative forces have a connection that comes across in this elegant and considered hang.

Parker was in Sydney to create the installation for the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (MCA), and it’s her first major show in the Southern Hemisphere. The exhibition is a great example of how public and private funding can come together to make something extraordinary happen.

Patrons Catriona and Simon Mordant AM joined the NSW Government via Destination NSW – and under the banner of the tenth edition of the Sydney International Art Series – to bring this incredible show to Sydney.

It is also a demonstration of inter-museum relationships globally; the MCA enjoys a strong connection with the TATE (UK), from which it has loaned the two large-scale installations for the exhibition, Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View (pictured top) and Thirty Pieces of Silver for this exhibition.

Comprising over 40 artworks from the late 1980s through to the present, this survey exhibition however does not feel bogged down with the kind of encyclopedic lens we so often find with such shows, but rather has lightness.

Parker has the incredible capacity to take the everyday and transform it into the extraordinary – objects that offer unexpected and haunting scenarios, spatially exploded and suspended in time. They are held in a kind of stasis that begs consideration.

Take for example the installation, Subconscious of a Monument (2001–05), which is comprised of thousands of dried lumps of earth that have been excavated by engineers from under the Leaning Tower of Pisa in Italy to help stabilise it.

Subconscious of a Monument 2001–05, installation view, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, 2019. Private Collection, Turin. Image courtesy the artist, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia and Frith Street Gallery, London. Photo ArtsHub

Or Parker’s War Room (2015), made from discarded red paper strips – detritus salvaged from the Poppy Factory in Richmond, London, which produces Remembrance Poppies to memorialise the Great War of 1914–18.

It is an incredible metaphor of loss; the vacant cut-outs creating a silent shrine. One can’t help but situate this work alongside Mark Rothko’s famed chapel in Houston (USA), or Ellsworth Kelly’s chapel-like work Austin (housed at Blanton Museum of Art in Austin, Texas), both of which use the simplicity of form and light to convey “spirituality”, and moment, in a non-religious contemplation.

War Room 2015, installation view, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, 2019. Image courtesy the artist, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia and Frith Street Gallery, London.© the artist. Photo ArtsHub

The exhibition is anchored by these and another two major installations.

Probably the most impressive – and photographed – is Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View (1991), an ordinary garden shed that has been blown up by the British Army and reconfigured by Parker into a mass of burnt wooden shards and household objects.

Illuminated by a single light bulb at the centre, its dramatic shadows complete the work. The other is a silent hovering collection of silverware collected from Parker’s friends, car boot sales and charity shops, then flattened by a steamroller.

It is impossible not to be impressed by these major works, but this exhibition equally offers small kernels that equally deliver a considered wallop.Take for example the suite of objects presented in a flotilla of vitrines. Here is a doll cut in half by the Guillotine that beheaded Marie Antoinette, sheets infused with chalk from the White Cliffs of Dover, a shotgun saw off by criminals, a Colt45 gun in its early stage of production, and news headlines drawn by children.

Described as ‘Avoided Objects’, Parker said she hoped they would be a ‘catalyst for thought’.

Shared Fate (Oliver) 1998. Installation view Museum of Contemporary Art Australia 2019. Photo ArtsHub

‘These works, which might be just as labour intensive as my installations, describe something that was “not quite” an object,’ continued Parker.

There are works on paper that are created from silver reclaimed from photographic fix – laments on death – while others have been created from rattlesnake venom and anti-venom.

Collectively, their message is one against violence.

While many of the objects across Parker’s oeuvre feel familiar – even nostalgic – she uses them to open a conversation that is very much a consideration of our time. She doesn’t shy from the political.

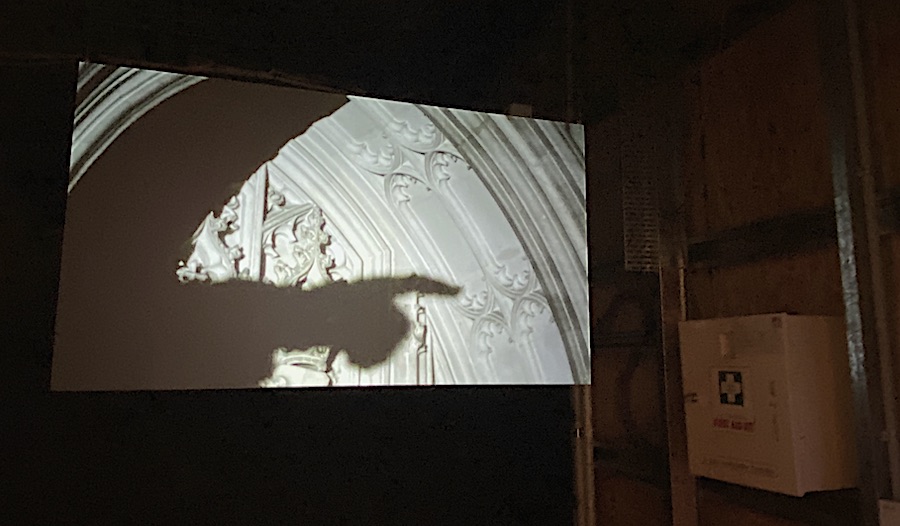

Presented in wall cavities are a suite of video works made in 2017 when Parker was appointed as the first female Election Artist for the United Kingdom General Election.

‘In this highly visible role, she observed the election campaign leading up to the 8 June vote, met with politicians, campaigners and voters and produced artworks in response,’ explained the MCA. They are an interesting proposition as the UK teeters on the precipice of a Brexit decision.

The video Left Right & Centre (2017) was filmed by a drone at night in the House of Commons, Westminster; Thatcher’s Finger (2018), offers a kind of shadow-play featuring a sculpture of the former Prime Minister; while Election Abstract (2018), a larger work in a dedicated gallery – is a visual journal of Parker’s experiences of the snap election that were posted on the artist’s Instagram feed.

Also included in the exhibition is Magna Carta (An Embroidery) (2015), a 12-metre long work hand-stitched by over 200 individuals that recreates the Magna Carta Wikipedia entry. It is an interesting take on doctrination, historic document, and contemporary interpretation.

For me it connects with a work, again caught in a wall cavity, which shows a group of men (largely off-camera) who manufacture thousands of crowns of thorns for Easter pilgrims to Bethlehem.

Made in Bethlehem (2012) has been said to draw a potent comparison with the West Bank’s barbed wire without overlabouring the point.

This is a salient point. Parker finds the right balance without pummelling viewers on a topic, but rather takes audiences on a contemplative journey that allows them to find their own social conscience in the work.

This is an incredible exhibition and a rare moment for Australian audiences to see a comprehensive sweep of one of the most important artists working in our times.

★★★★★ 5 out of 5 stars

Cornelia Parker

Museum of contemporary Art Australia, Sydney

8 November 2019 – 16 February 2020

Curator: Rachel Kent