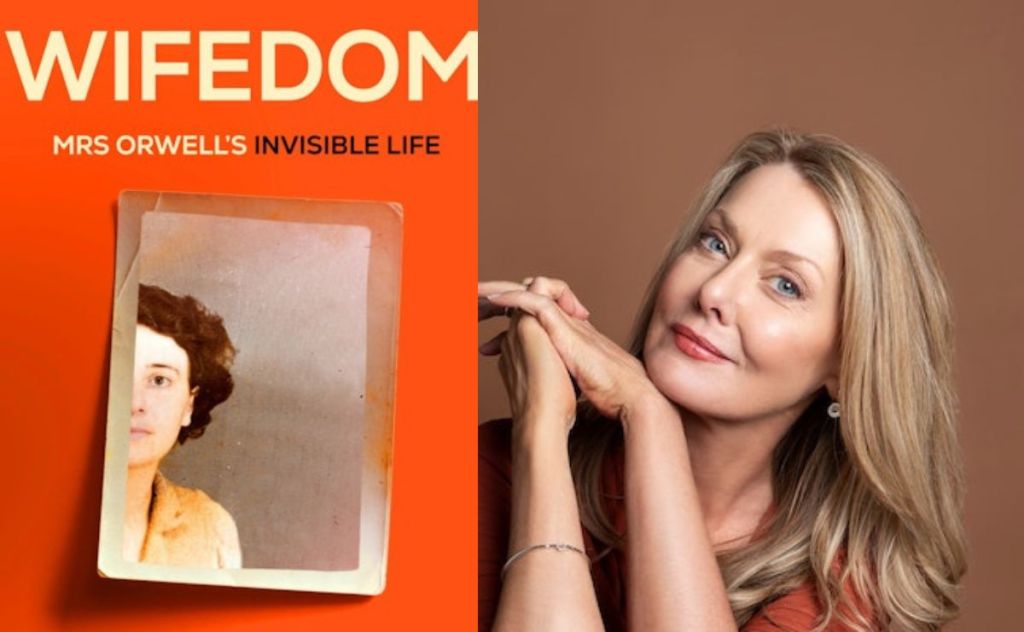

Anna Funder’s Wifedom brings us into the private worlds of Eileen O’Shaughnessy and Eric Blair, remembered by most as Mrs and Mr George Orwell. Resurrecting O’Shaughnessy’s voice from the depths of erasure, the author considers the many roles of wifedom, which go unappreciated and unacknowledged, and yet are necessary to the successes of so many men. Wives often become erased from the historical record, and their contributions remain unacknowledged, because (as Funder points out) time is gendered. Constructed around an impressive array of primary sources, including O’Shaughnessy’s own letters written between 1936 and 1945, Wifedom exposes this patriarchal power, and attempts to neutralise it through the creative unveiling of one woman’s truth.

Eileen O’Shaughnessy studied Literature at Oxford University under J R R Tolkein. Her own dystopian poem, 1984, was written 14 years before the publication of a certain identically-titled novel. This industrious and gregarious graduate married a gangly would-be writer named Eric Blair, and relegated her selfhood in order to support the reputation, achievements and public perception of the man who would one day be known as George Orwell. The emotional masochism and professional sacrifice that accompanied her marriage are apparent retrospectively, despite overt efforts undertaken by her husband (and history itself) to undermine the ways in which her influence vastly improved his work, and facilitated his pseudonymous success.

Unshockingly, the conditions enabling Eric Blair/George Orwell to work were not magically created by happenstance, but custom-created for him by his wife’s unceasing labour. Funder analyses instances in which women, including O’Shaughnessy, have been erased, minimised, relegated to footnotes or rewritten entirely, highlighting the status of wives as the original slaves, providing the invisible and unpaid sexual and domestic labour enabling men to create their great works.

Funder provides an array of fascinating insights into O’Shaughnessy’s role in helping her husband achieve his destiny, painting a vivid picture of a remarkable woman, largely forgotten due to patriarchal erasure. The author’s exploration of the creation and perpetuation of patriarchy touches on the nature of unspeakability, and rails against the theft of women’s lives, creativity and time.

Orwell famously defended Charles Dickens’ poor treatment of his wife, neatly separating the man from his work. But Funder probes deeper into past and present conceptions of cancel culture, taking the question further to pertinently include whether victims of injustice can ever be removed from their suffering at the hands of the men whose writing we elevate. A particularly misogynistic Orwell passage prompts Funder to wonder whether it’s possible to reconcile her altered perceptions of the author with her long-standing love of his books.

After all, the hypocrisy of patriarchal privacy silences women against their ill treatment, and silences society against holding men accountable for their actions. It conceals harms inflicted upon women, including O’Shaughnessy, who must engage in a form of interior double-speak to reconcile opposing perspectives of their reality. Funder expertly explores the ethics of excusing misogyny through the resurrected voice of this luminous woman.

The intentional concealment of women’s achievements is tragically commonplace, and Funder points out many instances in which the passive voice is deployed as a weapon of erasure. An opportunity materialised. A connection was made. Assistance was provided. Like the author, you will find yourself alerted to the question of, ‘Yes, but by whom?’ wherever passive voice is used, both historically and contemporarily.

Conspicuously missing from male-centric biographies, Eileen O’Shaughnessy is the real hero of Orwell’s life story. Her existence in the negative spaces of Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia reveals much about his acknowledgment of her contributions. The few times O’Shaughnessy is mentioned, he uses the phrase ‘my wife’, as opposed to her name, as if she is an object he owns, or a tool he uses. O’Shaughnessy’s poignant final moments are recorded in fittingly passive form, as one final act of malignant erasure. Warning: you will cry.

Wifedom transcends mere biography, providing astute historiographical analysis that will challenge readers’ perceptions of past, present and future realities. Functioning as a sagacious lesson against losing oneself, this brilliant book will resonate most with those who insist upon their own imagined equality, even as they shoulder the burdens of others – invisibly and largely unacknowledged. However, Wifedom should really be read by everyone, particularly those who have fallen prey to the structurally-misogynistic myth of the male genius.

Read: Theatre review: Off the Record, New Theatre

Meticulously researched and intelligently imagined, Funder’s masterpiece of creative non-fiction is exquisitely written with the humour, heart and boundless empathy Eileen O’Shaughnessy always deserved.

Wifedom: Mrs Orwell’s Invisible Life by Anna Funder

Publisher: Penguin

ISBN: 9780143787112

Format: Paperback

Pages: 464 pp

Publication Date: 4 July 2023

RRP: $36.99