‘This is a story about sanity, getting through one day and the next.’

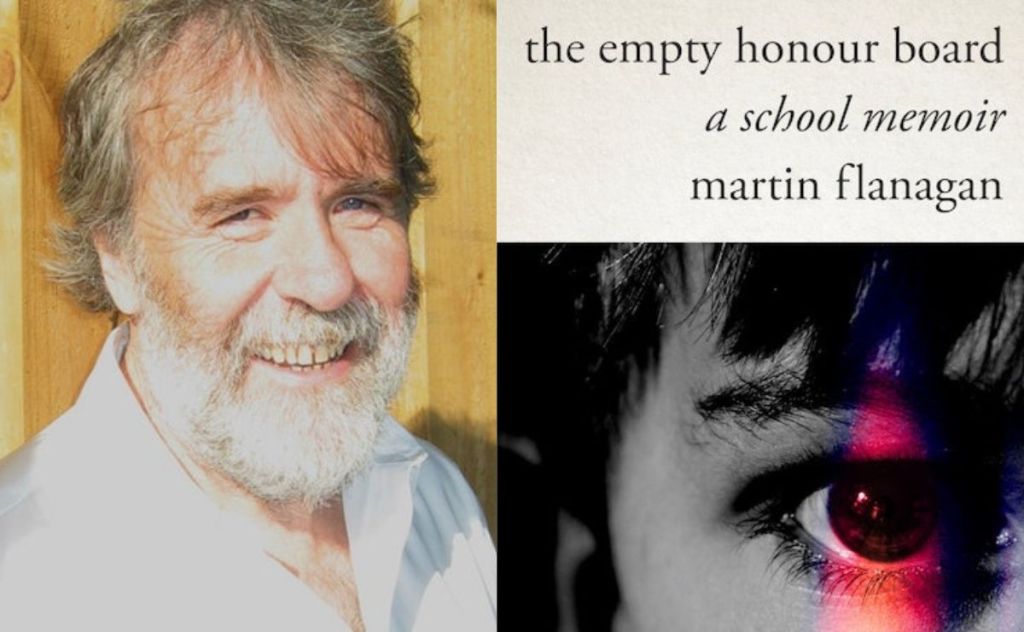

Martin Flanagan’s memoir The Empty Honour Board is centred on his harsh institutional experiences of a Tasmanian Catholic boarding school in the 1960s – but it enlarges its view to explore the ongoing legacy of these formative encounters.

With a terse, yet resonant, prose style, he follows the fissures of trauma that weave themselves through a life, and the risks of falling into these dark spaces. In doing so, he incorporates the perspectives of others, while applying compassion to both survivors and – most generously – to the abusers, for whom ‘getting through one day and the next’ was also a test of sanity.

That generosity may be a defining feature for some readers, particularly those who may (understandably) wish to see the Catholic priests that ran the school excoriated as inhuman abusers and paedophiles.

At the time in which Flanagan attended the school – which he feels obliged not to name to avoid legal pushback – there were 12 priests in charge, three of whom were later incarcerated for sex crimes against pupils.

And yet the author admits (without refuting these crimes happened) that the picture of the school as a virulent breeding ground for child molesters doesn’t quite square with his memories.

Some ex-pupils, he notes, for example, have no recollection of abuse. Meanwhile, his take on his own direct experience with predatory behaviour, involving a priest he calls “Eric”, and who is one of the three later to be imprisoned, is complicated. This encounter – as described in the book – could objectively be interpreted, at the very least, as exploitative and completely inappropriate. In fact, it’s one that he says his wife considers evidence he was sexually abused. But he writes: ‘I’ve never felt abused, not then or since … if someone claims to be offended but feels no offence, that person is a hypocrite.’

Elsewhere, as he delves into psychiatric and legal analysis of the priests, he captures a sense not of monsters per se, but of pathetic, inadequate men who are also victims, in their own way, of the institution.

‘It’s not about laying blame,’ he writes. ‘It’s about having a real idea of what those places are like.’

While potentially frustrating (even confronting), he draws on a personal and nuanced truth devoid of sensationalism, and this becomes ultimately the book’s unique strength.

This commitment to truth-telling, the complexity of human psychology in the context of an implacable institution, extends to not-so flattering depictions of his boyhood peers, the bullying ‘fascist politics’ of adolescence that he inevitably compares to the seminal high school text Lord of the Flies, which he was studying.

It also forces him to confront, with remarkable and powerful intensity, his own feelings of shame, that ‘inaction in the face of violence [which] seemed a colossal moral failure’. This ‘deep shame’, he says, ‘corrupts and corrodes’.

A sense of his own culpability is part of the ongoing trauma he feels. But again, he resists the inclination (or is unable) to impose a neat shape or conclusiveness to this psychological journey that continues through adulthood. He describes it as a ‘formless terror’ at one stage, as well as elsewhere literally preventing him from settling down (‘I only felt at rest when I was on the move’).

That the school is never named only enhances a shadowy sense of the formlessness of that “terror” looming over proceedings. Names of individuals are also often changed – and the admittedly somewhat clumsy way that Flanagan repeatedly tells us this adds to the sense of someone occasionally tripping over a murky and complex past.

Nothing is neat here, there is no black and white, memory is modulated. Even sport, although upheld as his great spiritual respite, a ‘magical thing’, is tainted somewhat. When he witnesses the violence of Australian fast-bowling in the 1970s against the hapless English batsmen, with the local crowd baying for blood, he’s reminded of the bullying culture of school.

To some extent, in the book’s latter half, it’s almost as if Flanagan is shuffling the reference cards in his mind, searching for the lines or patterns of coherence – and it may strike some as ill-focused, even contradictory, at times. But it’s also an expression of the ambiguities of life, and in refusing to patronise the reader with those neat conclusions, Flanagan achieves a rare sense of lived experience – as well an understanding of how that experience may have different meaning from individual to individual.

This is not a definitive account, but it deliberately doesn’t seek to be. In fact, its meditative refusal to judge and to impose an overarching moral view seems to make it a more valuable part of a broader historical document.

Read: Book review: West Girls, Laura Elizabeth Woollett

Flanagan’s terse line that sums up the book simply as a statement about ‘sanity’ and survival, ultimately stands as a wryly backhanded reference to the myriad psychologies that underpin his story, and the often mysterious residual effects of carving oneself into a shape that fits a system. However, while definitions of survival and sanity may mean different things to different people, Flanagan’s book asks us to look with some compassion and understanding – if not forgiveness – at whatever form they take.

The Empty Honour Board: A School Memoir, Martin Flanagan

Publisher: Penguin Random House

ISBN: 9780143779131

Pages: 224pp

Publication Date: 25 July 2023

RRP: $24.99