Artists’ language groups are acknowledged at the end of this review.

Walking into Tony Albert’s 5th National Indigenous Art Triennial at the National Gallery of Australia, the tone is set immediately.

Gone are the staged institutional photographs of the artists showing. Rather, a suite of 15 portraits by artist Vincent Namitjira introduces the artists (and the collectives they represent) in this exhibition.

This is artist-led; this is artist-defined.

Reading Albert’s Indigenous Triennial:

What does artist-led mean?

After the Rain is a pivotal point in, ‘taking a breath, planting new seeds, just taking that moment to reflect’ says Albert, but it is also a cleansing for the future way in which exhibitions, within the power-structure of the institution, can be framed.

Albert not only shows by example in this exhibition, but questions the elephant in the room: Why is the Triennial so inconsistently timed, despite its namesake? What is the commitment of the National Gallery to allowing sovereignty in Indigenous exhibition making?

Since the inaugural Triennial in 2007, this is the first time that an artist has been handed the baton to deliver this important survey. ‘That is not symbolic; it is structural and fundamentally shifts the model from one of representation to authorship, placing artists not only in the exhibition space, but at the decision table,’ says Albert, welcoming media to his exhibition.

This is further stamped on our early impression with the work of Aretha Brown – a graphic wallpaper in black and white that wraps viewers within its arc of history – from the Endeavour to our failed Referendum on an Indigenous voice in Parliament.

I am reminded of the work of African-American artist Kara Walker wither her decisive cut-outs with clout. But this immersive work is all Brown. She even took herself on the replica Endeavour to channel the past and make sense of the present.

Brown’s work – like Namatjira – penetrates the institution and has been used as the marketing for Albert’s Triennial. It’s young; it’s street savvy; it’s deceptively simple – and through it we start to map a new future, one ‘After the Rain’ to call on Albert’s theme, that starts to extinguish the barriers.

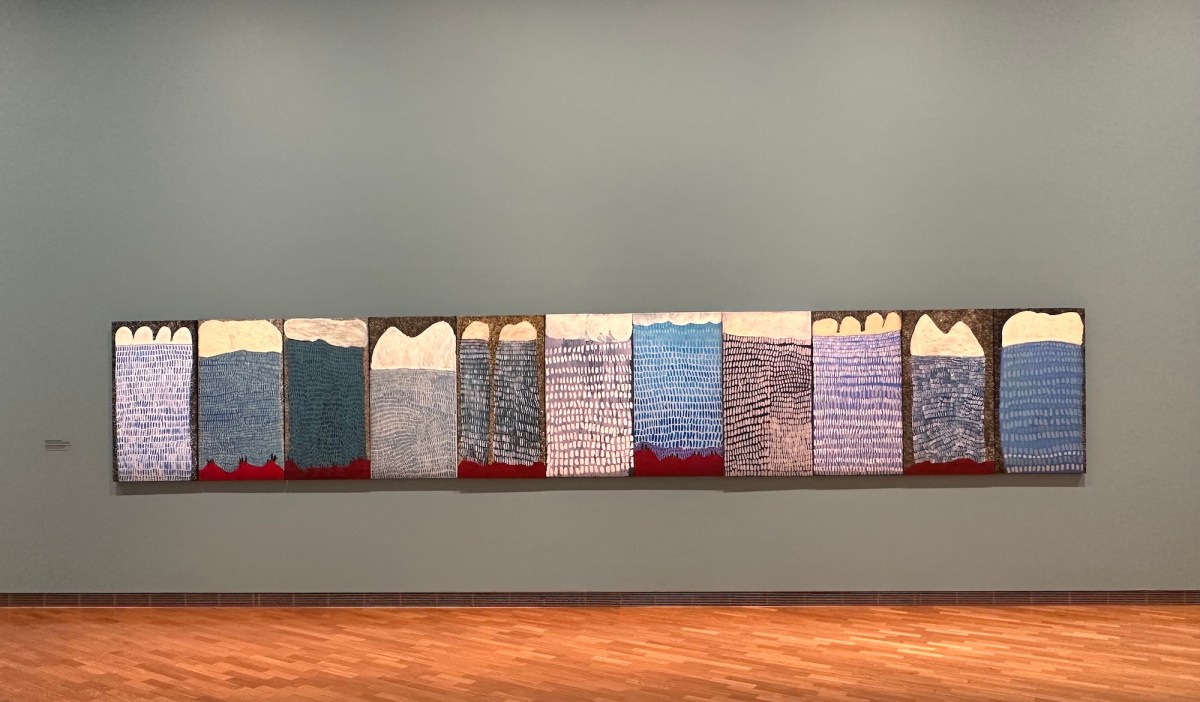

It forms one of the bookends of this incredible exhibition: Brown is the youngest artist in the group, while the final gallery presents the work of Grace Kemarre Robinya, who is in her mid-80s. Her suite of 11 paintings is the most literal interpretation of Albert’s theme, bursting storm clouds over Country.

Her distilled, simple repetition begs us to ask, what knowledge do our old people hold? What knowledge is in a single raindrop?

The simplicity of this work, like Brown’s at a fraction of her age, starts to untangle our very complex histories, and its repetition offers a sense of evenwhere – that timelessness that is a constant meter for resilience.

Chapters in Albert’s epic narrative

Between these framing poles, each room positions the viewer in a different immersive engagement. There is little bleed between the galleries; they are resolved exhibitions in their own right. So, moving through this Triennial, it feels like a sequence of chapters in an epic tale.

There is no better installation to illustrate that through line or chapters across history, than the installation of Aurukun artist Alair Pambegan, which sits in the same space where his father, Arthur Pambegan, presented his work for the inaugural Triennial, Cultural Warriors curated by Brenda L Croft, 18-years earlier.

Pambegan takes the painted red-black-white stripes of ceremonial body paint and wraps the room in this rhythmic palette to embody his story of the Flying Fox. Over 600 carved flying fox totems are suspended above the viewer, and Pambegan has carved the two brothers in this story, Wuku and Mukam, in a first. It has a breathtaking, immersive quality.

Working artist-to-artist, Albert has pushed these artists to make their most seminal works, and Pambegan’s installation is a great example of that safe zone Albert creates within the institution – and it’s palpable to audiences.

Albert’s exhibitions within an exhibition

The move between Pambegan’s installation and the next gallery is like a defibrillator – that heart jolt that jumps one alive. Equally palpable, it’s an installation of nine mortuary tables upon which are projected images of Country overlaid with designs from Gamilroy country.

It is such a rich and layered piece by Warraba Weatherall; stark and confronting in the bare space, which feels slightly haunted with its soundscape. An urban artist in the spotlight at the moment (current survey at Museum of Contemporary Art and inclusion in the next Biennale of Sydney), here Albert pushes our understanding and comfort levels within contemporary Aboriginal Art, with the sheer sophistication of Weatherall’s work.

In Mother Tongue, Weatherall uses the metaphor of the mortuary table as a trigger for the loss of language on the one hand, and the loss of habitat and homelands on the other, thanks to deforestation, resource mining and our changing climate.

It has a deep resonance with Jimmy John Thaiday’s film Beyond the lines, which appears later in the exhibition – a lament for his sea country of Erub Island (Torres Strait), which is being consumed at a frightening rate by rising sea levels. You become silent when you watch it, transfixed by its beauty and chilled by its warning.

Read: Kaylene Whiskey review: offering super-powered conversations

Community is the foundation to everything

Moving from that darkness of Weatherall’s work, Albert journeys us to a place of light and community. The next gallery presents the House of Namatjira. It is a somewhat congested space, and moves between installation, glass, ceramics, watercolours, photography – and yet, the central narrative of all holds it beyond tipping into chaos, just.

Albert put the count at 10 artists, Vincent painted 15 portraits, but in this space there are 68 artists represented, bringing together Albert Namatjira with his grandson Vincent Namatjira, the Hermannsburg Potters and Iltja Ntjarra (Many Hands) Art Centre.

It is another exhibition within an exhibition that dives the viewer into one of the most known histories of Aboriginal art with Albert Namatjira’s story, and yet, it’s also one of the most unknown – the story of his home as the first Aboriginal person to be granted citizenship, but denied land.

What we see in this space is a to-scale replica of Albert’s house made out of stained-glass windows in collaboration with Canberra Glassworks, its transparency echoing the translucency and colours of Namatjira’s watercolours.

The Hermannsburg Potters have deviated outside of their spherical pots in a first, to recreate objects from his home: his boots, favourite tin cup and easel. Keeping with the theme, Albert has selected from Gallery’s collection of 97 works by Namajira, watercolours that have water in them, including some rare seascapes.

There is so much in this room to take in – layers of history, community and love.

That idea of love frog-leaps viewers into the next space, to the work of Dylan Mooney, again one of the younger artists in this exhibition. In contrast, the space is clean and bold, using technology to make Mooney’s intimate portraits of lovers, and then punch them into billboard-scaled devotions that celebrate same gender relationships.

With the tour of this exhibition, these banners can be hung outdoors in regional and remote communities, promoting those tough conversations not often had. This idea of active participation is expanded, with visitors encouraged to sit down within the space, and pen a love letter, which will be delivered courtesy of Australia Post.

Read: Thinking bigger: talking First Nations partnerships with Fondation Cartier

A push and pull across time and space – Albert keeps us thinking

This push and pull between tradition and contemporary, history and now, senior artist and next generation, flows across this exhibition like the rain itself. It is metered and deeply considered by Albert, and we get that again moving into the next Gallery with the work of senior Yirrkala artist Naminapu Maymuru-White’s celestial bark paintings, Milŋiyawuy (Milky Way).

It again invites participation – to drop onto a cushion, slow down and be immersed by Yolŋu ways of being through a suite of 42 bark paintings and a ceiling installation.

Clustered in the final Gallery, are the aforementioned rain paintings of Grace Kemarre Robinya, alongside the diarising paintings of Thea Perkins (her mum, Hetti Perkins, was the curator of the last edition of the Triennial, Ceremony, in 2022), and new works by Yarrenyty Arltere Artists, the soft sculpture weavers from Alice Springs – three generations in one room, and connected by kin.

Albert explains to ArtsHub: ‘I knew that this is an exhibition that is going to challenge people, it is going to add weight to our brains, to our shoulders. But as Aboriginal people, what do we do with that? We cleanse ourselves, we learn from that, and we use elements to move forward in light. And I wanted to use rain as this cleansing at the end of the exhibition.’

Exiting the exhibition, visitors pass through a veil of textile raindrops and birds created by Yarrenyty Arltere Artists. It again offers a physicality – a human touch that brushes the skin – and narrows the worlds that so often divide us in contemporary Australia.

Albert’s final twist

In a final twist, Albert reimagines the ‘exit through the gift shop’ phenomenon, as a salute to Aboriginal enterprise, rather than an institutional lining of pockets.

He has invited Blaklash’s Troy Casey and Amanda Hayman to create a model home, where audience are shown 101-style how they can live with bespoke, ethical and unique merchandise made by Indigenous artists.

It is a fascinating addition by Albert, aimed at elevating the place of Aboriginal design enterprise, and makes the point that it not only sustains these communities that we’ve just seen in this incredible exhibition, but is often the other side of the coin (metaphorically and literally).

As copyright battles have been fought in our courts and in Parliament for better legislation in recent years, Albert turns to soft politics to impart value to a broader public who voted no to the Voice referendum.

It is yet another example of the kind of renewal that ‘the rains’ can bring in the hands of artists, sewing seeds for a better future.

5th National Indigenous Art Triennial: After the Rain, is showing at the National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra6 December through to 26 April 2026, before travelling nationally through 2026-2027 to seven venues.

The Triennial is supported by First Nations Arts Partner Wesfarmers Arts. It is a free exhibition.

ARTISTS:

- Tony Albert Girramay/Yidinji/Kuku-Yalanji peoples

- Albert Namatjira, Western Arrarnta people

- Hermannsburg Potters, Iltja Ntjarra Art Centre and Vincent Namatjira, Western Aranda people

- Alair Pambegan, Wik-Mungkan people

- Aretha Brown,Gumbaynggirr people

- Blaklash, Troy Casey & Amanda Hayman

- Dylan Mooney, Yuwi people, Zenadth Kes/Torres Strait and South Sea Islander;

- Jimmy John Thaiday, Kuz/Peiudu peoples

- Naminapu Maymuru-White, Maŋgalili people

- Thea Anamara Perkins, Arrernte/Kalkadoon peoples

- Yarrenyty Arltere Artists and Grace Kemarre Robinya, Western Arrarnta/Arrernte/Luritja/Anmatyerr peoples

- Warraba Weatherall, Kamilaroi people

Discover more arts, games and screen reviews on ArtsHub and ScreenHub.

The writer travelled to Canberra as a guest of the National Gallery.