Cultural representation in theatre is essential. It reflects our Australian identity, offers a vital platform for marginalised communities, and is profoundly enriching for audiences. But accurate, respectful and ethical representation is also important.

Theatre practitioners must know how to appropriately incorporate the features and elements of other cultures meaningfully in their work. Without this, the representation becomes superficial, which risks alienating audiences and further marginalising – or even insulting – vulnerable communities.

So what can be done to get cultural representation right? What do theatre professionals need to consider when using elements of different cultures, what power dynamics are present in cross-cultural productions, and how can we move beyond surface-level diversity to engage deeply with other cultures?

Cultural representation in theatre – quick links

What cultural representation is

Cultural representation is more than just featuring performers from diverse backgrounds. It also includes performing sacred practices, displaying traditional symbols, using foreign languages and employing instruments, sets or costumes from a culture distinct from the theatre-maker’s own.

These practices, symbols, and terminologies can be modern as well as historical; using modern Korean slang, for example, is just as valid a representation of culture as performing Bharatanatyam, an Indian classical dance form. Both these types of representation carry meaning because they are displays of another culture.

Read: Opera for the Dead: ghosts in the theatre

‘All creative work is cultural,’ says Katrina Irawati Graham, a writer and director who has worked as a cultural safety advisor across theatre, film and television.

Noting the importance of appropriately framing such work, she says: ‘Oftentimes, when people talk about cultural work, what they mean is non-white cultural work. This obscures the centring of whiteness and hides an unequal power dynamic that is constantly being created, recreated and strengthened. That’s racist.’

Cultural representation can also be framed beyond a racial or ethnic lens. Theatre-maker Jessica Moody notes it can refer to representation of disability. Moody is Deaf, a term that as she says is ‘used to describe those who are actively engaged with the Deaf community, and share common culture and sign language’.

Representing the Deaf community’s practices, forms of communication, and lived experiences – and the experiences of all people with disabilities – must also be done with care.

How to incorporate cultural practices respectfully

The act of framing can be a highly nuanced one, due to the various cultural elements a production might include. And just because a work has cultural elements does not mean that the cultures are automatically well-represented.

Tiffany Wong, Founder and Artistic Director at Slanted Theatre, says: ‘Culture isn’t something you can simply lift and drop into a show – it comes with lived experience, training and lineage.’

Because of this, theatremakers assume a responsibility to portray the cultures their work represents with fairness and accuracy. There are numerous ways they can do so. Graham’s first suggestion is to improve one’s racial literacy:

‘It’s [about] understanding what racism is, our part in the systems of racism, what story sovereignty is, and the roles of meaning and power.’

She also raised the importance of engaging a cultural safety consultant early to create a cultural safety plan based in power equity.

Creating a cultural safety plan and conducting training

To find a cultural safety consultant, Graham said the best bet ‘is to look at who is working as cultural safety on shows in your area and reach out to them. It’s a case of word of mouth, looking at the programs and asking people involved in the show. If the answers come back saying they were invaluable to the production, then definitely reach out to the consultant!’

When it comes to creating a cultural safety plan, ‘all key creators should be involved in that discussion,’ she says.

‘It should include questions like, what is the benefit to the community [and] who might be impacted versus to the people who are doing this? If you’re writing it, why is this important to you? What are you trying to say? What’s the impact it’s going to have on you personally, on the story itself, or on the people receiving it? Also, do we need to ask people in the community if there is a cost we haven’t thought about?‘

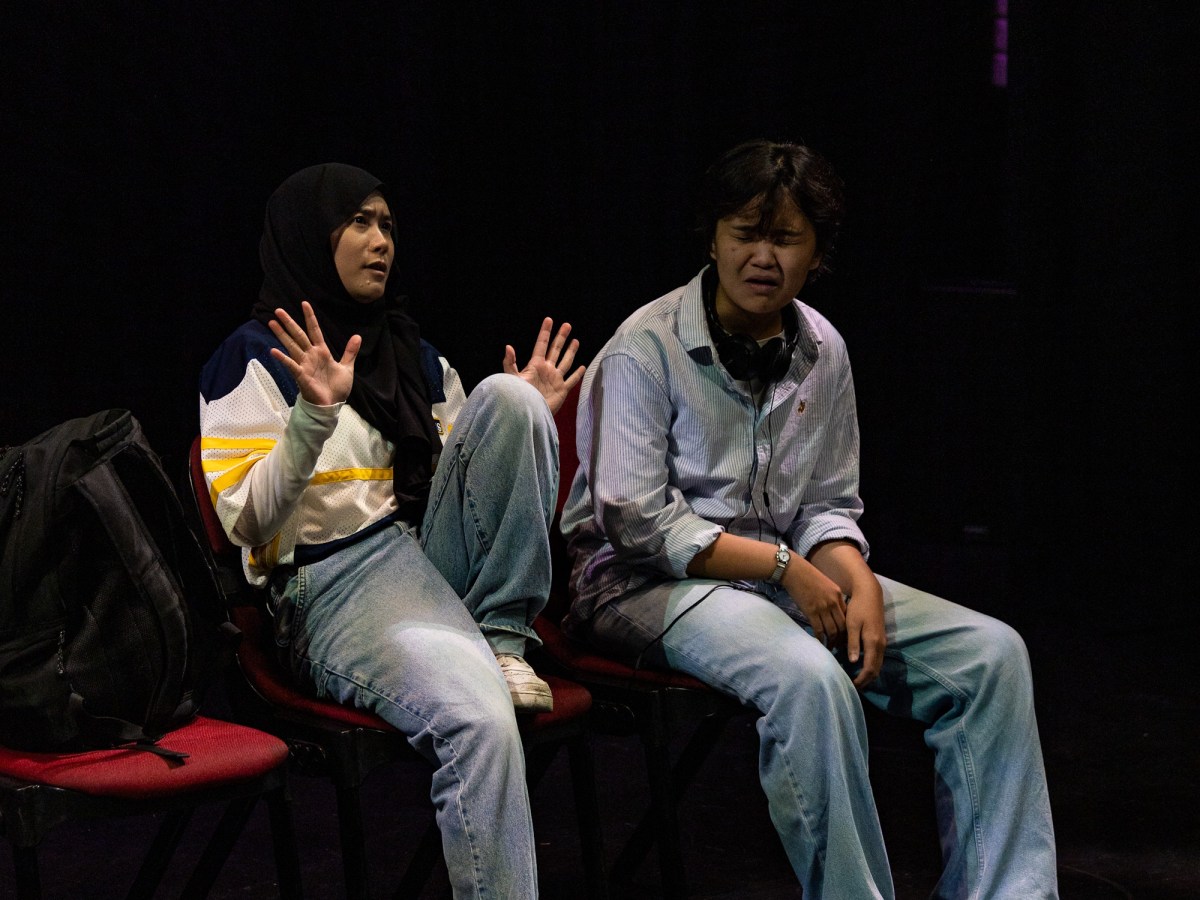

Such community outreach is essential, especially when representing communities outside the theatre-maker’s own. On a past project, Graham engaged a Muslim man and a hijab-wearing Muslim woman to review the Muslim content of a script because she knew that different genders might assess the work differently.

Graham also noted the importance of training and care. ‘I do a one-hour cultural safety training with everyone at the start of a production, and then I have a follow-up workshop that’s around community care and private care. And then I’m always following up with people personally. Like I’ll call or text them, “How are you going? Hey actress, I know you’ve got a show on today. How’s it going? How are you going this week? Do you need any extra support?”’

‘I love that kind of practice. It’s incredibly nourishing, with incredible levels of shared care and protecting what we love. The more that we can learn to love each other, then the more we can learn to protect each other.’

Acknowledging and sharing cultural labour

Wong identified that such dynamics force artists to perform cultural sense-checking responsibilities, a labour which is rarely acknowledged and often quietly expected. To address those dynamics, she said that decision makers must be trained, and institutions must recognise that cultural responsibility shouldn’t ‘sit silently with artists in the room’. She also mentioned the importance of knowing one’s limits.

‘At Slanted Theatre, we’re very open about what resources and knowledge we don’t have. Some years that means producing fewer works, because we know we don’t yet have the right people or understanding in place. That restraint is an ethical choice, not a lack of ambition.’

Moody said the best way institutions can support Deaf artists and storytellers is to invest in them. ‘This investment,’ she says, ‘will require so much more time and resources than what you’re used to, because not only do we need to create the outcome, we also need space and support to nurture the creation process and the people involved for the desired (and truthful) outcome/s.’

She adds: ‘But continue nurturing Deaf works and playing the long game. The payoff will be so lush.’

Graham said the best practice for safe cultural representation is to create a cultural safety plan that uses an anti-racist lens to outline possible risks and mitigations that work within the resources of the production to ensure all cultural needs are met.

She said that Diversity Arts Australia’s Principles for Cultural Safety, Accessibility and Inclusive Practice is a good start, but the plan which practitioners ultimately use must be tailored.

‘Cultural safety plans, like all safety plans, are bespoke to the work, the artists, the story and the producorial resources,’ Graham said.

‘Find someone with excellent racial literacy who you trust – who understands the cultural context of the work and the intent of the creatives. Bring them on board. Trust is essential. They need to be able to assess the cultural safety risks and work with the production and intent to mitigate those risks.’

Inspiration or appropriation?

When cultures are portrayed meaningfully, the effects can be powerful. Shervin Mirzeinali is a composer whose work Nazri tells the story of a ritual of communal giving, in which the dancer represents the chef. It took its name from an Iranian food-giving ritual, featured Indian and Iranian musical instruments the tabla and tombak, and had a multicultural cast of percussionists.

‘I interviewed each percussionist for an hour and asked them to come up with performance techniques that weren’t conventional,’ Mirzeinali explains.

‘After that, I gave them an instrument from one of the other cultures. I asked them to hold it, to see what their experience with it is like, and how they would like to perform with it. I recorded the sound and the video of all those processes. That’s how we could extract different techniques evolved over different cultures and exchange them’.

Such cross-cultural communication, which leads to the creation of new techniques, performance styles and discussions, is valuable. It forces a discussion of what inspiration and appropriation are, and where the line is drawn between the two.

When asked about where this line is drawn, Graham, Wong and Merzeinali differed in their responses. For Graham, it revolved around power. ‘It’s about who’s holding the power, who’s making the meaning, who the work is going to be received by and the sovereignty within that.’

Wong said the line between inspiration and appropriation isn’t fixed, and isn’t always clear. Yet that lack of clarity doesn’t weaken the process, it sharpens it. ‘The problem isn’t being near the line – it’s pretending the line doesn’t exist.’

To Mirzeinali, the line is between intention and genuineness. ‘It’s the intention that was specifically behind how the cultures were used. You can definitely understand if somebody did something with another culture fully understanding what they were doing, or they just did it because it looked interesting.’

He added: ‘People can also understand genuineness. They can sense if the creator cared enough about the work or not. If they’re looking at the culture from a superior angle, I may not enjoy that.’

Cultural representation: a restriction or an opportunity?

Including different cultures in a creative work creates an obligation on theatre practitioners to ensure accurate and ethical representation. Whether that restricts their artistic freedom is, again, a question of framing.

Graham noted that theatre-makers inherently balance creative restrictions, of which cultural representation is just another part. Mirzeinali said the extent of the restriction depends on the artist’s approach and priorities, as ‘some are more on the conceptual side and some on the aesthetic’.

Moody said that artistic freedom and a lack of creative restriction are not mutually exclusive. To her, the restriction lies in the repetition of dominant narratives and theatre-making practices ‘to the point that we collectively ignore or are discouraged to explore and show alternatives’.

Wong believed that even though aesthetics are sometimes prioritised over cultural truth, a balance can be struck – if the responsibility isn’t framed as a restriction.

‘Cultural accountability can sharpen artistic freedom by making the work more precise. The real responsibility of theatre-makers isn’t to get it right, but to try their hardest – by asking the difficult questions, acknowledging gaps, and being honest about what they don’t yet know,’ Wong explained.

Read: Iksha II review: myth made human at Seymour Centre

Ultimately, there isn’t one way to get cultural representation ‘right’. Discussion, education, understanding power dynamics and knowing one’s limits are useful ways of framing the process to achieve meaningful depictions of other cultures. And theatre-makers should not see these as a burden. Instead, they are a fantastic opportunity to engage with new perspectives.

Working with other cultures transforms the way we tell stories, breaks stereotypes and improves inclusivity. It carries risk, but without the courage to take that risk, such cultures may not get promoted at all – limiting our ability to engage with their rich worlds.

As Moody says: ‘Creativity is an infinite source; within creativity are endless potentials and opportunities to demonstrate practices that infuse integrity and care for-and-with my community.’

‘What a beautiful encounter it would be for the industry and wider culture to witness the liberation of a much (much) wider margin of stories.’

This article is published as part of ArtsHub’s Creative Journalism Fellowship, an initiative supported by the NSW Government through Create NSW.