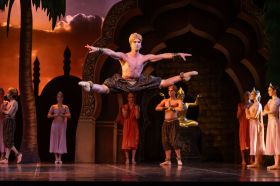

Opera Queensland’s 2016 production, The Barber of Seville. Photo by Steve Henry.

Though all of us in the arts aspire to be open minded, secretly most of us carry around certain stereotypes and assumptions about art forms other than our own.

‘Fringe theatre – it’s all a bit rubbish really,’ we might think to ourselves while toiling away on our latest symphony. ‘Opera – expensive and elitist much?’ we sniff as rehearsals begin on our new indie show.

While these stereotypes exist inside the arts, they have put down even deeper roots among the general public, watered by ignorance and fertilised by the mainstream media’s tendency to rely on clichés.

In the first part of this series, representatives from the opera sector and fringe festivals tackle some of the most persistent stereotypes about their art forms and explore ways we can counter the clichés and foster more genuine debate.

OPERA IS AN ACQUIRED TASTE THAT MOST PEOPLE CAN’T AFFORD TO ACQUIRE

The perception that opera is too expensive for most people to afford is a common one, and according to Jack Symonds, Artistic Director, Sydney Chamber Opera, the stereotype ‘is entirely true. Sydney Chamber Opera is simply an outlier. Our ticket prices reflect our place in Carriageworks’ Artistic Program – all of which is $35. It is a source of great pride for us that our work is accessible to an audience that wouldn’t otherwise believe themselves capable of affording opera.’

That question of belief – that people automatically believe they can’t afford tickets to the opera or other so-called ‘high art forms’ – is something that troubles Lindy Hume, Artistic Director of Opera Queensland.

‘I think there’s a kind of comfortable perception, a kind of comfortable position on – not necessary just opera but on what have kind of been called the “elite art forms” in opera, ballet et cetera. I think there’s a kind of comfort zone in saying “we can’t afford to do that and it’s out of reach”.

She continued: ”I think it’s a bit lazy because it clearly is inaccurate. There are ways of getting to see opera and ballet for less money if you were so inclined, but just being able to pass it off with that one line, “we can’t afford to,” kind of gets you off the hook of even bothering to try to understand these art forms.’

Hume wonders whether opera companies are doing enough to promote cheaper alternatives. ‘We have this amazing $25 ticket offer for Opera Queensland and we’re in our third year of that now, and they always sell out and they have a positive effect on main price sales in parallel. So to summarise, it’s a kind of a furphy to say that it’s not possible to afford opera.

‘Top price tickets at Sydney Opera House on Saturday night – who can afford that? No-one can afford that. But there are other ways of getting access to opera pretty much everywhere in the world,’ Hume said.

opera is elitist…

Black tie openings are another opera stereotype, but the art form isn’t just the playground of the rich, said Symonds, who notes that Sydney Chamber Opera’s audience is not the usual opera crowd. ‘The majority of them come from theatre and contemporary performance, with the expected smattering of the new music True Believers and only a small crossover with heritage classical music.’

He also acknowledged that mounting traditional, large scale operas was ‘insanely expensive’ but added, ‘I totally understand why a large company needs to charge what they do to put on something enormous. Whether or not these productions on the grandest possible scale always fulfill their artistic aims and wants of the audience is the question we should really be asking.’

Black tie events exist but are only a small fraction of the operatic experience, said Hume.

‘Audience behaviour, for instance, when we have our Playhouse season, it’s exactly the same audience protocols as going to the theatre – it’s very relaxed, you can just come in your jeans, it’s not a dress-up sort of thing. And acceptable behaviour is whatever you find it to be’ she said.

‘There is, I guess, a certain large theatre etiquette for the Opera House that I guess people observe, and I guess there’s a truth to the glamour of the opening night of the opera, but that’s like 5% of the experience in pretty much any opera company in the world. The rest of it is much more like real life.’

Opera Queensland’s activities with regional audiences are certainly helping to break down stereotypes and clichés.

‘A lot of that stereotyping … it simply doesn’t exist in regional places. When we do our regional tours of our productions, the really excellent productions that we take out on tour with great casts and the QSO and so forth – the audiences in regional centres have a much more of a sense of “this is just a really exciting piece of theatre and music”. There’s no snobbery – it’s just a lot more authentic. So that’s an interesting thing,’ said Hume.

‘I think there’s a kind of learnt behaviour, it’s a little bit temple-like. People feel like “oh I’m at the opera, I have to behave in a certain way,” and I think that exists less and less. It certainly still exists in certain black tie type environments but when we go out on tour in regional Queensland some of the audiences are much, much better because of that more relaxed atmosphere.’

…and difficult

Another opera stereotype would have it that the art form itself, despite featuring some of the most passionate music ever written, is also – let’s not mince words – difficult.

‘Opera can indeed be dense, difficult and elitist, but also the complete reverse,’ said Symonds.

‘There is a place for all these kinds of works on the spectrum, and audiences hungry for them. Second-guessing what is and isn’t difficult can lead you to make some pretty wretched artistic compromises – I’m sure we’ve all seen examples. By the same token, there is certainly a strand in contemporary music and theatre which I believe is simply “wilfully difficult” and designed as a smokescreen for a paucity of genuine ideas and expression. If a new audience member sees just one of these shows, they can possibly be turned off for life.’

‘Elitism is a more complex issue,’ Symonds continued. ‘Some art aims high and necessarily requires a complexity of thought to engage. If we’re just trying to feed people the easiest possible medicine in the belief that art is “good” for you, then why are we artists at all? I don’t advocate for or against elitism. I am however against knee-jerk anti-intellectualism. Each opera and production should be seen in the context of both its creation and re-creation.

‘Putting on [work by the British composer Harrison] Birtwistle in a small town that has never had opera in any form is the most arrogant kind of elitism. However, there is some undoubtedly great work that requires the audience to possess some kind of musical, formal, linguistic and dramatic pre-knowledge if they are to really get into it. How is the artform to develop if every single work has to start from the assumption that the audience are total newbies that need to be spoon fed? It’s just insulting to all concerned,’ he said.

Turning the tide

The mainstream media plays a key role in perpetuating opera stereotypes, such as the clichéd representation of the overweight diva in a horned helmet singing in some difficult foreign tongue.

Hume said: ‘We’re all so aware of that stereotyping and the desperate need to change it. So I do think it’s more about – with all respect – the laziness of the media and those sorts of go-to stereotypes of this is what an opera singer looks like, this is what an opera audience looks like, this is how they behave.

‘We’re all working to change that reality but unless that’s picked up and celebrated and engaged with from a narrative perspective outside the companies, you’re sort of fighting a losing battle,’ she said.

At Opera Queensland, part of the strategy of overcoming such barriers is to take the art form directly to the people – particularly people who haven’t encountered its power before.

‘You kind of have to bring people along on a very particular journey, and a very personal journey, where they have actual personal engagement with a company. For them to see in person, at first hand, that the reality is very, very different,’ Hume explained.

‘And that’s why we’re so involved in much more participatory projects; that’s why we get ourselves so involved in collaborations, with say a contemporary dance company like Expressions or Dance North – both are companies we’ve worked with at OperaQ. Suddenly there’s a lot of people exposed to something they might not normally have been exposed to and they see that these opera singers can move and they can act – certainly there’s not a helmet anywhere to be seen,’ she laughed.

‘FRINGE’ IS A CODE WORD FOR ‘SECOND RATE’

Thousands of artists – the majority of them professionals who are donating their labour and skills – create and present works in Australia’s fringe festivals every year. Many such works are ground-breaking, inventive, exploratory and remarkable. A handful are not. And yet, the stereotype persists that there’s something a little second rate about fringe performances in general – but why?

‘Fringe means anything from the edges – it’s about work from outside the mainstream. That’s exactly what makes it interesting. People can be deeply challenged by new forms or by content that expresses a new point of view, often by otherwise marginalised voices. When we are challenged, people can immediately fall into “that’s not art” or “that’s not very good” when in fact, it’s an exciting new form or challenging content,’ said Simon Abrahams, Creative Director and CEO, Melbourne Fringe.

Abrahams is also quick to acknowledge that that’s not always the case.

‘Fringe can also mean open access, and sometimes that also means work by artists at all stages of their career. So Fringe Festivals can be full of work of the highest calibre presented alongside work that probably needed more development. That’s the joy of removing the gatekeepers – embracing everything that comes in with the spirit of adventure and diversity that means a single work can’t represent a whole sector,’ he said.

‘Fringe theatre is full of extraordinary performances that brings new perspective on our work, and help us to discover new artists, new art forms and new things about the world around us. It’s exactly why I’ve devoted my career to it.’

Sydney Fringe Festival Director and CEO Kerri Glasscock describes the ‘fringe = second rate’ cliché as an ‘outdated and incorrect stereotype’.

‘It is unfortunate that people associate “alternative” or “independent” with less quality; it is possibly a hang up from days past where there was very little to choose from between professional commercial productions and amateur theatre. But that is no longer the case – in fact many artists now work professionally in the independent sector or work in smaller fringe spaces by choice,’ she told ArtsHub.

Read: Equity developing new agreement for indie theatre

The best way to challenge this outdated stereotype – to create an alternative, more truthful narrative about those working on the fringes – is to ‘go regularly to “fringe” shows, venues or festivals,’ Glasscock said.

‘You’ll soon see that more often than not they feature the same actors who appear on our mainstages or screens, and can be more inventive, interesting and engaging than mainstream or mainstage works.

‘Fringe or independent theatre encourages exploration and a freedom of expression, the opportunity to test out new ideas, develop new works and push the boundaries of form and function – that of course doesn’t always work, but more often than not it does, and when it does you are rewarded with a gem of a show. Some of the best works I’ve seen in recent years have been in small alternative spaces or at Fringe festivals. So be brave and venture out – you might just be surprised,’ she concluded.

In part of two of this series, we will explore stereotypes around dance and orchestral music.

melbournefringe.com.au

operaq.com.au

sydneychamberopera.com

sydneyfringe.com