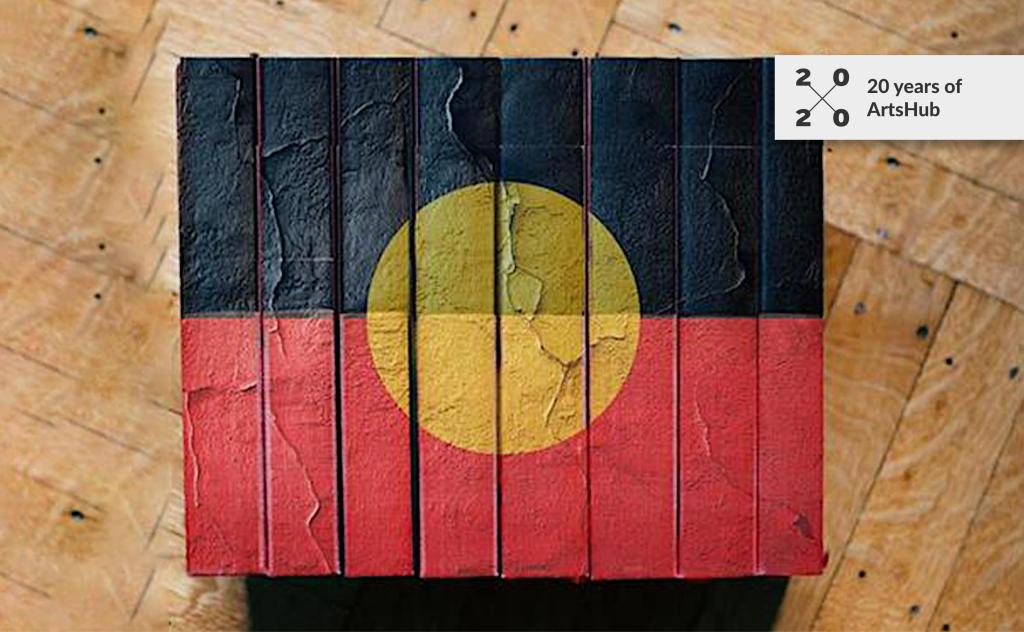

First published in August 2019 – and the inaugural article in our First Nations Arts Focus series –

guest writer Karen Wyld takes a look at the rise of Blak writing in Australia (to coincide with Indigenous Literacy Day, held earlier this week). This looking back and pitching forward is part of ArtsHub’s 20th anniversary celebrations – to revisit the stories and milestones that have shaped the arts sector, and what still needs to improve.

Through a sector-wide approach, and growing readership, the future of Australian literature and publishing is destined to be even more blak.

Firstly, I should explain why I’ve used the term blak. Blak is sometimes used by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations and people to reclaim identity language and re-assert power. It was first used by Destiny Deacon in her 1991 exhibition Blak lik mi. And it features in the title of the annual Blak & Bright literary festival, which showcases First Nations writers and literature.

Blak words, white paper

On the continent now known as Australia, First Peoples have been writing since the frontier wars. Attempting to appeal to the humanity of colonisers and settlers through letters, these early works documented injustices and often put forward solutions.

The first Aboriginal-authored book was written by Ngarrindjeri inventor and writer David Unaipon in 1929. The second, by Noonuccal writer/poet Oodgeroo Noonuccal, was published in 1964 under the name Kath Walker. Publication of First Peoples’ authored novels, poetry and autobiographies gradually increased. By the 21st century, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander writers, storytellers, journalists and academics had expanded into every medium and every genre.

Who wants blak books?

In addition to creative expression, First Peoples often use writing as a form of resistance, truth-telling or assertion of agency. These works create change in a non-threatening manner; allowing readers’ to reflect on biased worldviews within settler-colonial societies.

Readership of First Nations works is not an issue. In the Australia Council for the Arts and Macquarie University’s Reading the reader: a survey of Australian reading habits, 63% believe that books authored by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander writers are important (only 6% viewed these books as unimportant).

Social determinants of writing

Everyone needs access to education, health & wellbeing services, stable housing, nutritional foods, and a source of income. Beyond these basic rights, everyone deserves access to specific education and supports to pursue personal and career choices.

For writers, this could include affordable access to technical training, support networks (mentors, writers groups and industry experts) and technology (equipment, internet and IT literacy).

Shared technology/working spaces, upward social mobility and increased tertiary education completion rates has made a difference for many First Nations creatives, but a good education or job doesn’t fully mitigate the impacts of intergenerational disparity and systemic racism.

Read: First Nations leadership is about letting go, and holding on

What’s needed

Targeted awards, fellowships, scholarships and other opportunities have made a difference, but there is more that can be done to support First Nations writers – including addressing biased worldviews and systemic barriers.

Rachel Bin Salleh, Magabala publisher and writer, expressed the need for change in a recent interview in Australian Book Review:

‘I do think that concentrating on getting good stories from literate peoples may be a narrow way of looking at the world. Statements by some non-Indigenous publishers that they have ‘standards’ when it comes to First Nations writing are also extraordinarily limiting. Honestly, you mob seriously need to think outside the box and open up to different ways of thinking.’

More research could be beneficial, to evaluate Australian literature and publishing bodies’ capabilities to respond to First Nations writers and their works.

Evidence-based, culturally-responsive improvements within Australian literature and publishing could result in increased awareness of:

- How non-Indigenous organisations replicate systemic inequities and whiteness.

- Barriers to writing, and how to break these down.

- Additional steps that may be required in researching, writing and editing; such as following cultural protocols and obtaining permissions.

- Cultural factors and relationships that enhance mentoring for First Nations writers.

- Connection between participation in the arts and wellbeing.

- Advantages of actively growing the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander literature and publishing workforce.

Read: Nginha ngurambang marunbunmilgirridyu: I love this country – but do you? (2018)

Looking to the past, while moving forward

The works of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander writers and storytellers, whether they are stories from deep time, contemporary or a fusion, are unique. Reading blak-authored books, with their truth-telling and generosity of sharing story, can assist Australia to come to terms with its dark past and move towards a fairer future. And if that’s not reason enough to pick up a blak book, then do it for the unique narratives and excellent storytelling.

Read: Why the arts sector needs to let Australia’s First Peoples lead (2018)