Last year, Australian artist Mike Parr buried himself under a street in Hobart’s CBD in a durational work titled, Underneath the Bitumen the Artist (2018) that saw him entombed for 72 hours, and caught the attention of global media. It was conceived to draw attention to the genocidal violence of nineteenth-century British colonialism in Australia.

Two years prior (2016), he had his blood drained to create a drip painting in an ode to Jackson Pollack’s Blue Poles at the National Gallery of Australia (NGA). And next week (16 November), Parr will perform another physically demanding new work, Jericho, in a closed performance undertaken in the early hours of the morning at Carriageworks.

The invitation reads: ‘Duration unknown. Further details unknown. This comes with a warning.’

For almost five decades Parr has built a multilayered and critical practice, often using his own body as the principal medium – ‘a relentlessly ongoing act of self-portraiture’ described Carriageworks. He co-established Australia’s first artist collective Inhibodress in 1970, and was formative in the development of conceptual art and performance art in this country.

News week’s performance follows, Towards an Amazonian Black Square (2019), presented on 24 October for the opening of the exhibition The Eternal Opening, which is a kind of restaging of Parr’s recent important works.

Central to the exhibition is an installation of an actual art gallery as an art object in a gallery, where real time and documentation become a blurred landscape. Sound conceptually heavy?

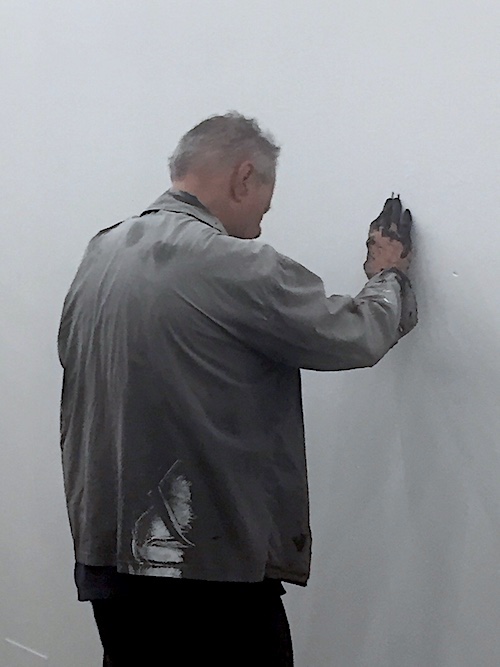

Mike Parr, The Eternal Opening, 2019, Carriageworks. Image Mark Pokorny.

While Parr’s work falls in the bracket of ‘thinking art’ it also captures a public’s imagination; his exhibitions are highly attended and his performances the darling of media. There is a fascination that precedes the work, and the man, and Parr usually delivers.

What is critical to his role in Australian art is the way he has actively interrogated the trajectory of art history and the role of the artist. There is no going back. And most are excited the questions his works raise.

The Eternal Opening

As the title of this exhibition suggests, it celebrates an ongoing conversation. Central to the exhibition is the new performance, Towards an Amazonian Black Square (2019), which draws on Parr’s outrage at the current wildfires in the Amazon rainforest.

The work is an urgent response to an ongoing environmental catastrophe, but uses art history to deliver its narrative.

Curator Beatrice Gralton explained: ‘Kazimir Malevich’s iconic 1913 painting Black Square became the ground-zero for non-objective art – it could be understood as an end-in-itself, or a window to a new beginning. Parr’s pursuit of art-after-Malevich has frequently required his own body to become the key object of interrogation. If Black Square is the severed head of painting, the limits of the body in real-time are the future of art.’

Mike Parr, Towards an Amazonian Black Square (2019), presented on 24 October 2019 for the opening of the exhibition The Eternal Opening, Carriageworks. Photo ArtsHub.

Watching Parr execute his black squares at Carriageworks, he oscillates between meditation and strain. It doesn’t feel bold or egotistical. He is incredibly attune to his physical limits, even when precarious on the extension of a ladder, he reaches left to right, top to bottom to exact the frame of the square – regularly touching the sticky paint to check its boundaries. It is reminiscent of braille. His eyes are closed, and another language is at play.

It sits in direct conversations with LEFT FIELD [for Robert Hunter] (2017), a dual-channel video installed in a built replica of Anna Schwartz’s Melbourne Gallery, where the original work was shown in 2017.

In it, Parr painted the Melbourne gallery, white-on-white with a roller from end to end.

Mike Parr, LEFT FIELD [for RobertHunter], 2017. Image: Zan Wimberley.

Parr opened Schwartz’s very first gallery in Melbourne; he again was the inaugural exhibition for her Sydney space at Carriagework, presenting the work, Milk (2008).

The pair have delivered in excess of twenty projects together, which in itself speaks of an incredible level or trust and patronage.

Schwartz said: ‘The reproduction of another gallery in The Eternal Opening, with its implied history and previous enactions is also a very moving evocation of the thoughts, actions and images expressed in this Carriageworks gallery by Mike Parr in his exhibitions during my time here: Milk in 2008; The Golden Age, in 2011; Easter Island in 2013 and Deep North in 2015, all also lie below the surface of this work in the memory of the viewer.’

The Carriageworks venue has been key to a number of Parr’s works. A video documentation of his 2016 Biennale of Sydney work, BDH (Burning Down the House), is also on display.

While a price tag was never attached to the Hobart performance (funded by the Museum of Old and New Art), for BDH Parr methodically doused with petrol and incinerated an 18 x 120-meter grid of work from his print archive, and their accompanying copper plates, worth around $750,000.

Detail, 2016 Biennale of Sydney work, BDH (Burning Down the House), Carriageworks. Photo ArtsHub.

Cost is also far more than a financial one – and this is perhaps the foundation of Parr’s performance practice – at what cost physical boundaries and environmental ones? Parr says: ‘Once you compromise the future, the past becomes unbearable.’

BDH (Burning Down the House) probes the role of art and the artists in a period where issues such as climate change and refugee policy have polarised communities and Governments globally. That environmental questioning – that cost – is again central to The Eternal Opening, seeking the endless answer.

How the re-performed / re-exhibited performance becomes eternal

In BDH (Burning Down the House), Parr destroys his archive of prints and plates. It is impossible to recreate this performance. But viewing it on a massive floating screen in the stark industrial venue, I could again smell it, and feel its heat.

Mike Parr, BDH (Burning Down the House), Carriageworks, 2016 Biennale of Sydney work. Photo ArtsHub.

Mike Parr, BDH (Burning Down the House), Carriageworks, 2016 Biennale of Sydney work. Photo ArtsHub.

It is an interesting aspect of performance art that Parr digs into with the re-presentation of LEFT FIELD [for Robert Hunter] (2017), and the performance Towards an Amazonian Black Square (2019), which is a further iteration of Towards a Black Square (2019), originally undertaken in Hobart during June 2019, when Parr occupied a large empty gallery for close to eight hours, painting unseen black squares on the walls in a futile attempt to achieve Malevich’s transcendent absolute.

Post performance, both video documentations are screened at Carriageworks, their sound recordings overlapping to create a ‘continuous displacement of this memory’, says Gralton.

This sound element is key, and through it, the audience also become performers.

‘It’s another level of the objectification of process and response. It seems to accentuate the null of painting-out action, of white-on-white, and of the loss of an artist, by accentuating a kind of eternal opening night as a portrait of the art world,’ explained Parr.

When conceiving The Eternal Opening exhibition back in 2017, Parr wrote of the LEFT FIELD performance: ‘After the performance a number of people wanted to talk to me about the behaviours of the audience. The audience had become increasingly noisy as people drank, socialised and asserted themselves. I was unconcerned by this. I rather liked this increasing hubbub, but in the aftermath I‘ve thought more about this “materialisation” as an aspect of the event that could be amplified.’

‘This unplanned aspect of performance art can be very revealing… that the unprecedented state-of-affairs might be the real point of performance art because it is the outcome that no-one, neither the artist not the audience fully controls.’

Mike Parr

How do we define greatness

This suite of collected performances not long follows Parr’s major show at the NGA Foreign Looking (2016), which was the museum’s largest survey of a contemporary Australian artist, and coincided with the release of major monograph on Parr’s work.Read: Blood on the floor (literally) as Parr takes on Pollock

On commissioning this exhibition, Carriageworks Acting Director Euan Upston said: ‘Parr is an indomitable and uncompromising artist, whose commitment to interrogating art history and art itself has influenced a generation of practitioners. At Carriageworks, we are committed to presenting work that is “artist led”.’

It is a view shared by the organisation’s new CEO, Blair French: ‘Mike Parr is a central figure in the story of Australian contemporary art. His practice is characterised by rigour, by a relentless commitment to enquiry and by a spirit of generosity. ‘

Parr represented Australia at the Venice Biennale in 1980 (along with Kevin Mortensen, Tony Coleing) – a benchmark that most Australians regard as having made it. He returned to Venice in 2015 at the invitation of curator Anthony Bond, for the installation, The Ghost Who Talks at the Palazzo Mora.

He has exhibited at Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea, Milan, the Foam Musem, Amsterdam; BRUSEUM, Neue Gallery, Graz, Austria, and the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, India, among other elite international institutions, and a swag of Australia’s top galleries and art museums.

What these gongs perhaps demonstrates collectively more than ‘greatness’, is the perception of greatness, and how Australian art audiences have matured across the passage of Parr’s career.

I have witnessed several of Parr’s performances, and there is a decided growing swell or energy, as people wait with a weird respectful awe (not unlike the arrival of a pop star on stage) for Parr to appear.

This always comes with silence – both by the audience and the artist. In this new exhibition, the role of the armature of the faux gallery defining the space structurally, also defines silence and anticipation as a form that is quite palpable.

These are not always short engagements. And there is no rulebook on the protocols of engagement. However, we seemed to have collectively worked it out, and as a result have become hungry for more Parr.

How do you collect that moment, capture that integrity?

In recent years, several books have been published on performance art and its rise to the hallowed halls and vaults of museums. It has always existed, but we have not always understood how to keep it in the present.

Mike Parr has led us on that journey in Australia, and this exhibition offers a next chapter in understanding.

Schwartz concluded: ‘Having worked with Mike Parr for more than thirty years it seems to me that the replication of The Eternal Opening represents the possible viewing of a lifetime’s practice as a single intensifying work.’

Mike Parr: The Eternal Opening is the fifth in the series of Schwartz Carriageworks artist commission since 2015, including Katharina Grosse (2018), Daniel Buren (2017), Francesco Clemente (2016) and El Anatsui (2015).

Mike Parr: The Eternal Opening

Carriageworks

25 October – 8 December 2019

Co-performers: Fiona Chow, Linda Jefferyes and Glenn Thompson

Curator: Beatrice Gralton