The title of Édouard Louis’ play Qui a tué mon père (Who Killed My Father) conspicuously doesn’t end with a question mark. As Louis makes clear in the text, he knows who killed his father: the successive French governments of Chirac, Sarkozy, Hollande and Macron. By cutting and restricting access to welfare and disability benefits (and humiliating those who rely on them), those governments and presidents ‘broke my father’s back all over again’ after he was disabled by an industrial accident, condemning him to work as a street cleaner ‘bent over all day and cleaning up other people’s trash’.

In fact, Louis’ father is still alive, but in his late 50s his health is now so severely compromised by heart disease, diabetes and obesity that he can barely breathe or walk, let alone leave the house or work. Louis is not just talking about literal death, however; rather his father’s slow but predictably early demise is the symptom of a political and economic system that degrades entire groups of people, as well as vast swathes of rural France collectively known as ‘la France profonde’.

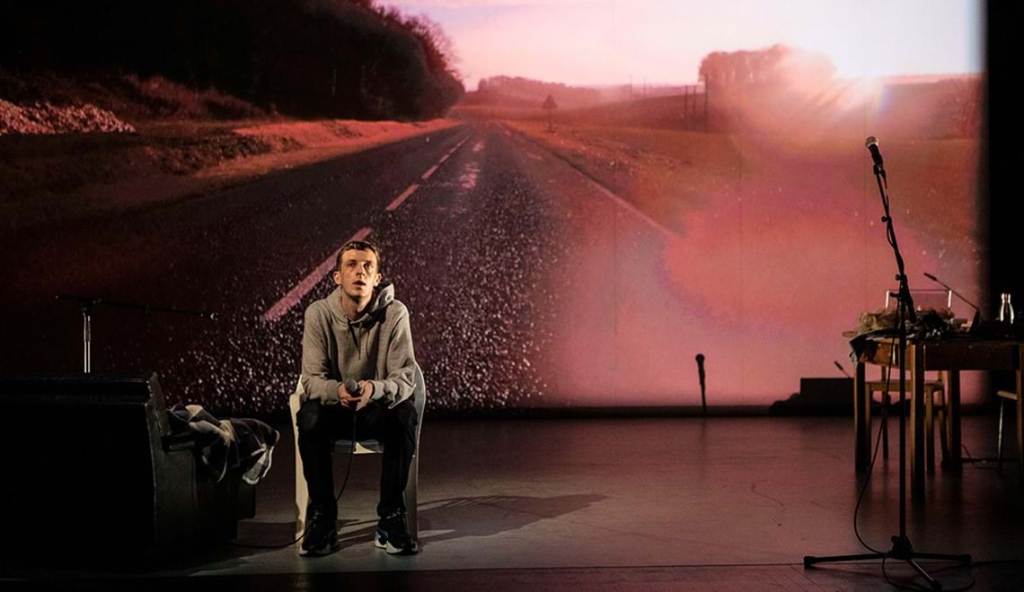

Director Thomas Ostermeier’s elegantly simple staging emphasised the domestic aspect of a play that consisted primarily of a son’s monologue to an absent father. Nina Wetzel’s minimalist set comprised a few items of furniture scattered around the stage: Louis’ writing desk with his laptop and a few piles of books and papers was an upstage anchoring-point to which he repeatedly and compulsively returned. An empty armchair downstage facing away from the audience drew his focus whenever he silently contemplated his father or approached and spoke to him.

At the back of the stage, Sébastien Dupouey and Marie Sanchez’s large-scale black-and-white video projections provided social context with images of an impoverished rural France, including largely empty highways and streets, semi-abandoned towns and villages, desolate fields and smoke-spewing industrial estates. These were interspersed with occasional family snapshots, including an atypical but revealing photo of his father at some kind of celebration dressed in female clothes, make-up and wig. There was an equally revealing photo of Louis himself as an eight-year-old dressed in a party hat, Zorro mask and cape, while performing a Céline Dion song in the family living room (which his father ignored before walking out).

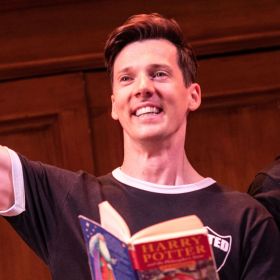

Louis’ performance in the show as his adult self was remarkably smooth and accomplished, whether delivering the text in mostly quiet, undramatic tones, or breaking out into alternately exuberant or desperately attention-seeking lip-synched dance routines to 90s pop songs. These memorably included Britney Spears’ ‘Baby One More Time’ and Whitney Houston’s ‘I Will Always Love You’ – the latter in homage to his father, who reluctantly bought him a VHS of The Bodyguard as a childhood birthday present.

Ostermeier had Louis using microphones, either hand-held or on stands, which were variously positioned around the stage, including on his desk and nestled in his father’s armchair. The device supported Louis’ intimate tone of delivery, while also ironically reinforcing the sense that he was adopting a public persona that was to some extent constructed, even when he was “playing himself” (much like the pop stars he lip-synched to, in fact).

The text was in French (with surtitles in English superimposed on the video). The only exception was a crucial section – which was addressed to the audience rather than to his father – involving an outbreak of family violence, betrayal and complicity on the part of Louis himself, which became a kind of confessional, and which he announced would be easier if he related it in English.

The final section of the play was the least successful. By reverting to an attack on individual politicians, followed by a closing call for “revolution”, Louis abandoned the complex story of his relationships with his father and family, in favour of a simplistic, demonstrative and histrionic diatribe that sacrificed his best qualities as a writer and performer.

Read: Exhibition review: Bruce Nuske, Samstag Museum of Art

Ostermeier’s staging of this sequence – with Louis donning the party hat, mask and cape of his childhood, pinning up images of the offending politicians on a washing line and throwing handfuls of magic dust at them – was intentionally regressive. It was as if Louis had abandoned the attempt to win his father’s love only to install Chirac, Sarkozy and co as surrogate fathers, so he could rebel against them in an act of childish insurrection. As such, it fell far short of revolution, despite the play’s final rallying cry.

Qui a tué mon père (Who killed my father)

Schaubühne Berlin and Théâtre de la Ville Paris

Dunstan Theatre

Director: Thomas Ostermeier

Writer and Performer Édouard Louis

Video: Sébastien Dupouey and Marie Sanchez

Stage Designer: Nina Wetzel

Costume Designer: Caroline Tavernier

Composer: Sylvain Jacques

Dramaturg: Florian Borchmeyer and Elisa Leroy

Production/Dramaturg: Elisa Leroy and Anne Arnz

Lighting Designer: Erich Schneider

Qui a tué mon père (Who Killed My Father) was performed 8-10 March 2024 as part of Adelaide Festival.