I was a bit concerned, and rightly so, for I have an aversion to long concerts. I think, on reflection, that I perhaps need to be cajoled into enduring them, as, for example, I never feel the time ticking away when I’m hearing an encore. Or, if the music is sublime, like at the four hour plus Steve Reich concert last year, I may not mind either. (Then again, the half-meditative state induced in the audience by Reich’s music may have been one of the reasons why the length was not so much of an issue.) If I know beforehand, however, I start to worry, and I certainly knew beforehand that the Sydney Philharmonia Choir’s latest concert, entitled Opera’s Triple Threat, was to be a long one, more than two and a half hours.

The Sydney Philharmonia Choir was the cause of a rather sore posterior around two years ago, from memory, when they gave a concert at Town Hall. The seats were woeful – plastic chairs with a suggestion of fabric masquerading as a cushion – and the concert – made up of many, many short pieces – kept prolonging and prolonging itself. I remember being very glad to be out of there, even if I had experienced some quite wonderful moments throughout the hours. And while this latest concert wasn’t in any way as severe as the one I’ve just recalled, I was still glad to be out of the Concert Hall and into the cool night air.

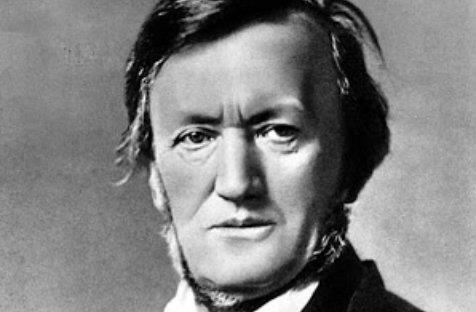

The problem started with the name. ‘Triple’. A triple threat is meant to be something, according to the blurb, that has ‘music, drama, and passion’ (although this critic would question whether passion is but a subset of drama). The ‘triple’ also refers to the three composers whose birthday was being celebrated – Benjamin Britten turning 100 this year, with Wagner and Verdi reaching the big two-oh-oh.

They were hamstrung by the name, basically. What I’m trying to say is that, in this concert where each composer got equal time to be celebrated, they should’ve got rid of one of them, and brought the running time back to two hours. My choice would have been Britten, which was the worst of the lot – though this is not to say that it was a bad performance, mind you.

Along with the Festival Chorus and the Sydney Philharmonia Orchestra, conducted by Brett Weymark (and Anthony Pasquill for a third of the Wagner), we were joined by soprano Cheryl Barker and tenor Stuart Skelton. Barker I have not seen of late, but Skelton was part of the fantastic opera-in-concert given by the Sydney Symphony and Vladimir Ashkenazy, where they performed Tchaikovsky’s Queen of Spades in one of the operatic highlights of the year, even with Opera Australia working next door and on the harbour. (And with a budget.) In the section dedicated to Britten, the audience was privy to a performance of selected moments from his opera Peter Grimes, including some arias, some choral moments, and many an interlude from the orchestra alone. The orchestra, as it was in all the sections for the evening, was in a rather delightful form, with Weymark pulling a real sense of drama out of them. Unfortunately, the tenor and soprano did not leave much of a mark with their respective arias, Skelton often drowned out by the orchestra, and Barker only having one real moment of beauty in ‘Embroidery in childhood’. By the end, it was the orchestra that came out on top.

All that changed, however, after the five minute ‘short break’, when we entered into the world of Verdi and Otello. Here, again, the orchestra was in fine form, and Barker and Skelton let loose in a most agreeable way. (Perhaps, also, one could relax a tad more as, the opera being in Italian, one didn’t strain to try and understand what words were being sung, something that was a mostly thankless task for one to attempt during the Britten, though this is more to do with the acoustics of the Concert Hall, one imagines, than the Chorus itself.) Here it was that the memories of the Queen of Spades came rushing back, here was some singing worth hearing.

An interval followed, and then Wagner took to the stage. Anthony Pasquill conducted a short selection from Lohengrin – Stuart Skelton providing the vocals – quite well, while Weymark came back to deliver Tannhauser (with Barker) and Die Meistersinger von Nurnberg (with both). All in all, it was some wonderful stuff – and it was great to hear the orchestra attack something that wasn’t baroque – but the concert was too long by a third. (One might say, however, that it is great value for money, which perhaps it is, but a critic should, I think, look for quality rather than quantity. You, dear reader, may feel differently.)

Rating: 3½ stars out of 5

Opera’s Triple Threat

Sydney Philharmonia Choir

Brett Weymark (conductor), Anthony Pasquill (conductor), Cheryl Barker (soprano), Stuart Skelton (tenor)

Benjamin Britten – Peter Grimes, Op. 33

Giuseppe Verdi – Otello

Richard Wagner – Lohengrin

Richard Wagner – Tannhauser und der Sangerkrieg auf Wartburg

Richard Wagner – Die Meistersinger von Nurnberg

Concert Hall, Sydney Opera House

9 June