Composers Monica Lim and Mindy Meng Wang come to Opera for the Dead from distinct musical lineages. Lim is drawn toward experimental sound and electronic expression, while Wang leans into classical traditions and the guzheng’s deep historical catalogue.

Together, they created a compelling tension in this performance, one that mirrors the work’s central inquiry: how traditional Chinese rituals of death, grief and mourning might translate into contemporary practice, particularly within diasporic and cross-cultural contexts.

Opera for the Dead review – quick links

Entering the ritual

From the outset, simply entering the space is part of the performance. The audience walks down the Yellow Spring Road – a dark, hazy corridor thick with artificial mist, invoking ceremonial incense.

The darkness is punctured by spasmodic flashes of light illuminating bowls of oranges – familiar offerings on altars – except here, they sit inside speaker cones suspended from the ceiling, vibrating among loose bells. Sound, symbolism and technology merge before the show has even technically begun.

At the centre of the room is a moveable stage – adjoined cubicles draped in long black fringing. A voice emerges in a quiet ode, or perhaps a prayer, chant or incantation. Then there’s an intense burst of sound as the stage and ensemble come alive. The cubicles split apart and the ensemble drifts away from one another, untethered, as though crossing into separate realms – plunging into death’s transformative journey.

In the Sydney Festival performance of Opera for the Dead, the audience’s gaze is constantly challenged and disrupted – by the veil of fringe, by shifting light projections, and by the bodies of other audience members moving through the space.

The Neilson Nutshell at Sydney’s Walsh Bay proves an apt venue, spacious enough to avoid claustrophobia, yet intimate enough to foster a womb-like closeness that brings people together in grief and in art. That it sits above the harbour feels symbolic, adding another layer to the work’s recurring motifs of death, passage and crossing over.

The moving voice of grief

Vocalist YuTien Lin, trained in Western opera, illuminates the work with a bold tenor and countertenor range. His voice moves from a guttural, almost death-metal rumble of grief to high, cooing, spectral wails – sounds of unspeakable loss and yearning.

Dressed in ceremonial white with a floral headdress, Lin leads the ensemble into a stirring expression of mourning: Lim on electronics, Meng Wang on guzheng, Alexander Meagher on percussion and Nils Hobiger on cello.

Read: WAKE review: queer cabaret from the Emerald Isle

Together, they form a lament for the deceased that might mirror the grieving cries of those left behind. As Chinese-Australian theatre icon Annette Shun Wah observed during the post-show Q&A, this is ‘a small group with a powerful sound’.

Visually and structurally, Opera for the Dead is ambitious and inventive. It plays deliberately with space and with how audiences must physically interact with the performance – echoing a funerary procession, bodies walking slowly through semi-darkness.

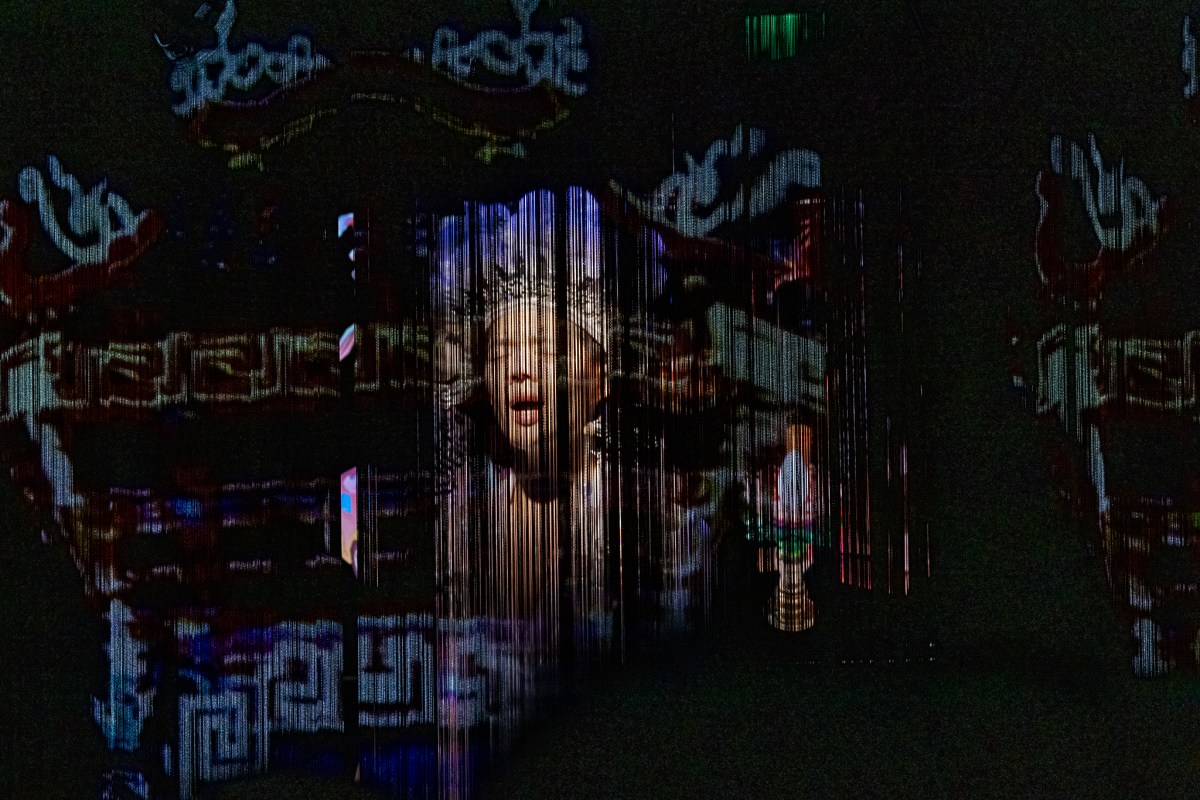

The work echoes Rainbow Chan’s Bridal Lament, particularly in its exploration of cultural liminality and how ritual is expressed between worlds. That connection is made explicit through the involvement of digital artist Rel Pham, who lends his signature aesthetic to both works, namely 80s-inspired neon pixel art and cyberpunk visualscapes layered with traditional Chinese temple iconography.

These visuals are punctuated by deeply personal images – dedications to loved ones who have passed, and photographs of fathers and grandfathers – which layers acts of remembrance directly onto the performers. The result is both ancestral and futuristic.

An artistic altar for dissonance as harmony

At its heart, Opera for the Dead examines rituals of death as forms passed through generations of mourners – rituals that, as the composers state, offer ‘a comforting structure while colliding dissonantly with contemporary life’.

This dissonance is held both gently and deliberately, without privileging modernity over tradition or vice versa. The work allows both to coexist, exploring cultural and temporal tension as something whole in itself. It is shaped by Lim and Meng Wang’s own experiences of grief, and by lives lived along cultural borders – finding beauty in the gaps, overlaps and contradictions of the human experience.

On Opera for the Dead’s website, visitors can find texts and prayers from the show, beginning with Digital Altar. This cyber-opera becomes precisely that: an artistic altar that honours culturally specific rituals while speaking to the universal ways we live, love and grieve.

Opera for the Dead | 祭歌 was staged from 15 to 18 January as part of the 2026 Sydney Festival. A Melbourne season is scheduled at Arts House from 28 February to 1 March.

This article is published as part of ArtsHub’s Creative Journalism Fellowship, an initiative supported by the NSW Government through Create NSW.