The first ever exhibition at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) devoted to First Nations creators is a feast of visual delight, sweetened with five exciting new commissions and seasoned with the works of celebrated Blak revolutionaries. How I See It: Blak Art and Film presents moving image, photography, installation, essay, documentary, new and archival data and a super-fly arcade video game; it shows us the omnipotence of the beautiful Blak mind.

Curated by Kate ten Buuren, the provocative new commissions by Peter Waples-Crowe, Amrita Hepi, Steven Rhall, Joel Sherwood Spring, Jarra Karalinar Steel and Jazz Money are bolstered by the staunch activism of Destiny Deacon and Essie Coffey OAM. With 2023 marking 45 years since Coffey’s documentary My Survival As An Aboriginal, 1978, How I See it: Blak Art and Film shows us the culmination of 45 years of unlearning racist policies; it takes us past the documenting of self and survival, to staunchly holding space as proudly diverse brilliant Blaks, who turn the lens around to say: ‘we can see beyond your fairy-tales and make believe, we can see you’.

As exhibition visitors descend the ACMI Gallery 4 stairs, the vintage luxe of baroque wallpaper with crystal teardrop sconces enhances a huge, ornate gold frame that displays Waples-Crowe’s single-channel video Ngaya (I Am), 2022. His signature dingo sketches with cut and paste collage work are animated into a layered drama that tells the story of Ngarigo Country, his ancestral lands. From a place of ceremony and sustainability, where smoke cleans the air to welcome a population of bogong moths, a series of still images is implanted and interplayed with moving bodies and bright burning lights. Layer upon layer: terraces, trams, people, machinery and even a twirling disco ball build onto the land with the fast-paced weight of a malignant tumour. On occasion Waples-Crowe enters the animation to survey this grave new world like it is something to see in a shop, something to own.

Plumes of smoke rise across the tangerine orange walls at the entrance to Amriti Hepi’s two-channel video installation Scripture for a Smoke Screen: Episode 1 – Dolphin House. Hepi is a consummate storyteller who uses body and dance to create paths towards understanding identity and representation. In this powerful work that references the 1960s NASA funded study that attempted to teach dolphins the English language, Hepi uses a minimal colour palette to magnify perspectives and to reframe history.

Performing various roles of evangelist, scientist, dolphin and consumer, Hepi explores the ‘gulf between lived experience and its representation, and how identity and ideas around intelligence are shaped, amplified or flattened’. In contrast to the high-octane striding of the evangelist, and introverted arch of the scientist, the wet-suited black dolphin is grounded, and lithely writhes across the different enclosures to which it’s subjected.

Multidisciplinary artist Steven Rhall, aka Blak Metal, redevises his critically acclaimed post-modernist installation Avert, 2017 by concealing it behind a bright candy-coloured corner of the gallery. Sniper spying slits draw us toward the walls where the core artwork, a large rotating pillar of neon words is partially concealed. Television screens situated at a distance present surveillance footage of the spy slits, so that regardless of how soft the flow of neon light or how joyful the coloured walls are, our inability to see/critique the core artwork while knowing that we’re being seen/critiqued creates an uneasy tension.

From unsettled instability, a bench seat in front of Diggermode, 2022 is welcomed. This cutting edge multi-channel video installation by Wiradjuri anti-disciplinary artist Joel Sherwood Spring, offers moments of deep reflection as sound bites of birdsong roll alongside the sounds of a shovel breaking through dirt and digging. Digging. Aspirational statues depicting mining success are followed by rusted, derelict machinery and dingy motels. At other times, the correlation between cataloguing, digital archiving and the message that information is a commodity is revealed through Spring’s pioneering use of digital technologies. His AI work reimagining Albert Namatjira’s landscapes to include mining machinery evokes both admiration and sadness, and is an exhibition high point.

Leading us into a Blak centred urban wonderland, Boon Wurrung, Wemba Wemba and Trawlwoolway multidisciplinary pop artist Jarra Karalinar Steel flips the colonial, White Australia narrative with More Than Just A Game, 2022. This playable arcade video game, where brightly dressed characters speak of dilly bags and digging for murnong ignites an awe of recognition and possibility. Like Destiny Deacon’s glorious legacy, where Blak faces dominate popular culture and have lead roles in commercial action films, Steel’s More Than Just A Game is enchanting.

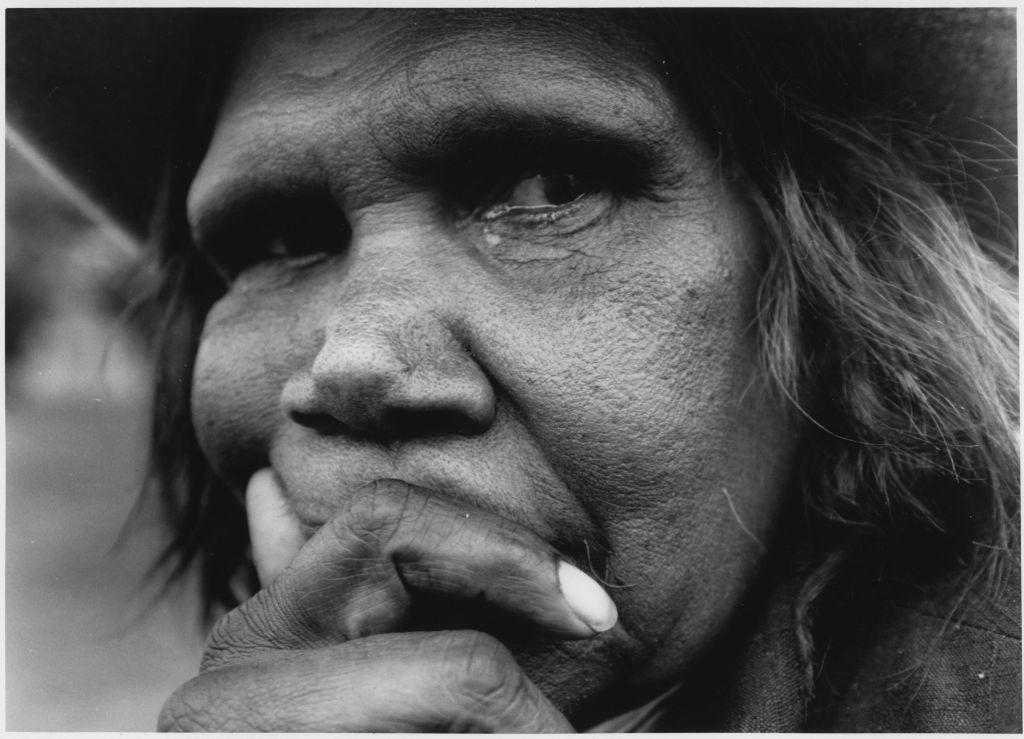

Award winning Wiradjuri poet Jazz Money’s Rodeo Baby! 2022 is a huge digital print on black silk that visually maps out Money’s experiences delving into film and sound archives. Iconic stills from iconic Aboriginal films and music highlight a romantic narrative that misrepresents the lived experience of Aboriginal people. This misrepresentation is smashed to smithereens in Essie Coffey’s seminal documentary My Survival As An Aboriginal, 1978.

Coffey’s truth-telling about her Brewarrina community is still relevant today and indicative of the disparity between urban and historic narratives about Blak lives on this continent. At 51 minutes long, the film is an opportunity to see Blak lives from the perspective of Blak eyes. It is a masterpiece of sovereign storytelling imbedded with social, racial and economic politics. As a pivoting force toward, How I See It: Blak Art and Film emboldens the Blak gaze as bold, brave and ready to be embraced in all its depth and variety.

How I See it: Blak Art and Film is at ACMI, Federation Square, Melbourne until 19 February 2023. Free admission.

For a full list of accompanying events and related film program visit the ACMI website.