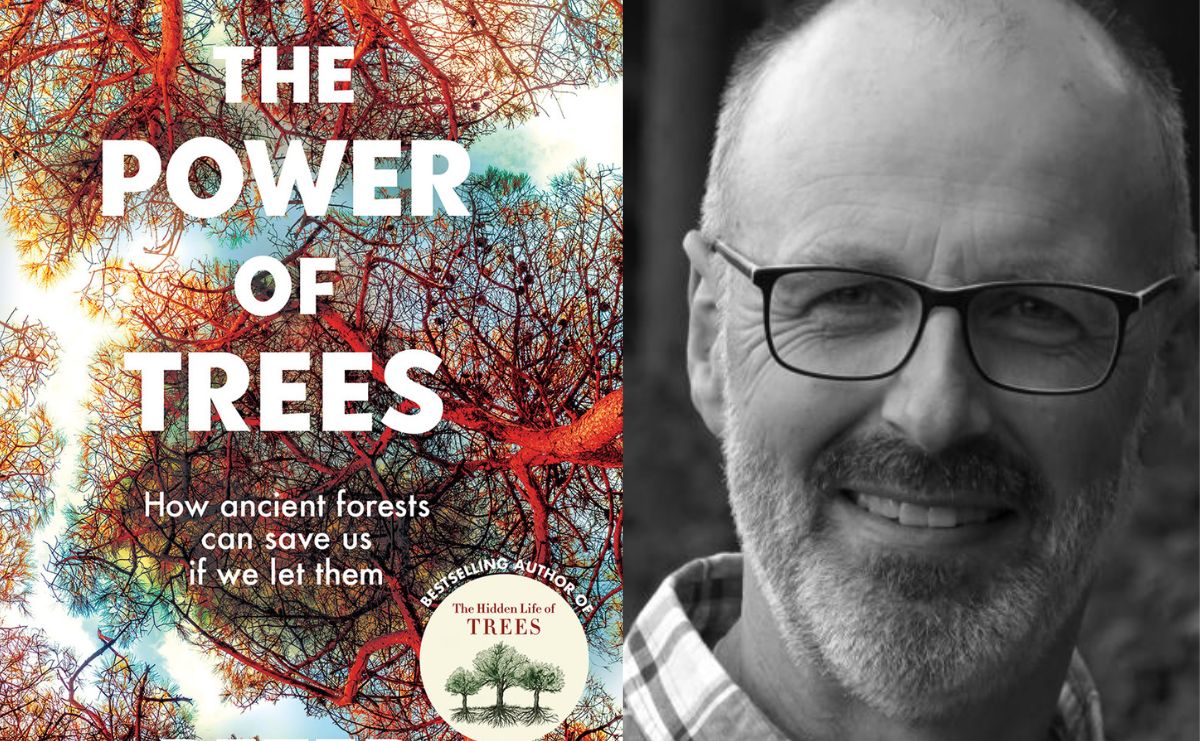

Peter Wohlleben, author of The Power of Trees, is on a mission. A German forester who has written for many years about trees and forests, Wohlleben’s titles include The Hidden Life of Trees and The Heartbeat of Trees, and his latest book is a call to arms to change the way forestry is practised and the way native forests are treated. Wohlleben’s bio says that while he previously worked in forestry for 20 years, he now ‘runs an environmentally friendly woodland in Germany, where he is working for the return of primeval forests’. This book may be the instruction manual for this work.

The subtitle of The Power of Trees is ‘How ancient forests can save us if we let them’. As powerful and emotive as these words are, the text does not provide answers for all nations and all forests, although some of Wohlleben’s research and statements about the role forests play can be extrapolated beyond Europe to other landscapes, including Australia.

Drawing on research, scientific evidence and in-depth exploration of the nuances of (primarily German) ecosystems, Wohlleben and his fellow researchers draw conclusions that are arresting and largely convincing.

However, readers outside the European landscape won’t find much to guide them in their own countries or with ecosystems that are different from the beech and oak dominated forests of Germany. Only once is Australian research relevant to home soils mentioned, while the forests of Brazil are noted a few times. For guidance, advice and inspiration on how the ancient forests of the Congo, Indonesia or China can save us, readers may need to go elsewhere.

These limitations for a local Australasian audience don’t diminish the overall message; the in-depth analysis of German forests, politics and the forestry industry; and the solutions that Wohlleben proposes. In fact, a book that profiled all forests and provided sweeping statements would be less useful or important.

The solutions to climate change, species loss and land degradation must be based on local conditions, so the deep dive into German ecosystems, forests, climate, weather, soils and animals provides a detailed and clear blueprint for German readers, governments and industries, while also providing inspiration and ideas for those outside Germany.

The Power of Trees is a blow-by-blow analysis of the impact of non-native spruce and conifer plantations, modern forestry and modern farming on the beech and oak forests of Germany, and the impact these practices are having on landscapes, communities, farms, climate and species loss. Wohlleben dives into the ground, investigating funghi and mycorrhiza.

He analyses the impacts of heavy machinery on the structure of soil, probing tree roots and millions of bacteria to understand the effects of compacted soil, drought and the removal of trees. After taking readers into microscopic worlds, he zooms out, like a hawk, and shows us the whole forest, nearby farms and cities, and the effects of forests on cooling and rainfall across the landscape.

Wohlleben writes about trees, ecosystems, roots and the many creatures who live in and among them in a fresh, lively – albeit slightly anthropomorphic – way. He believes forests and trees make decisions about their survival, protect and look after their offspring, and that crown shyness may be evidence of trees ‘respecting each other’s space’. For readers of The Hidden Life of Trees, some of this language will be familiar, and some may know that this style has been a source of derision in the past.

However, it’s this down to earth, conversational style that makes the book come to life and makes complex science accessible. He explains processes, such as the way trees access and use sugars at different times of the year, in simple, everyday terms. He writes about forests being ‘water pumps’, about rain as ‘aerial rivers’ and how the ‘die-off of deciduous forests creeps along in lockstep with the death of the plantations’.

The key purpose of the book is to argue, forcefully and convincingly, for a dramatic about-face in German forestry, even suggesting that forestry as a practice should be stopped. His claims and criticisms are backed by emerging science and new research, as well as practical observations of how the presence of forests changes the landscape nearby.

Wohlleben provides a stark example, citing a temperate map that recorded temperatures for 15 years, ending in 2017. As you’d expect, lakes were blue (cooler) while cities like Berlin were red (hottest). However, the most telling records were the impact of native woodlands:

‘If you glance at the temperature map quickly, it’s difficult to tell some of [the forests] from the lakes. These cool areas are ancient deciduous forests. The result of the experiment lay right there in front of us: beeches and oaks act like bodies of water. They cool the landscape so much that the temperature difference between a city like Berlin and an ancient woodland is about 15 degrees Celsius.’

Wohlleben goes on to add more fuel to his argument for the maintenance of old growth forests in favour of pine or spruce plantations, which are essentially large monocultures comprising one or two non-native tree species. ‘The results made it clear that these dismal monocultures can never replace real forests. The temperatures in the plantations were up to eight degrees Celsius warmer than those in the ancient deciduous woodlands. And then there is the fact that the crowns of these conifers catch more rainfall, so the ground below is significantly drier.’

Throughout the book, Wohlleben keeps coming back to the key message: the ancient forests of Germany should be left alone. They should not be removed and replaced with farmland, plantations or houses. ‘The results are clear,’ he writes. ‘Those who work against nature will never achieve a reasonable return on their investment.’ The same argument, for the same reasons, could be used in Australia, Brazil, Indonesia or Canada.

Although the landscapes, the monocultures that replace the ancient forests and the ways trees interact with each other and the climate are different across the globe, the overall message of The Power of Trees is universal. For specific evidence of the power of trees in other countries and other landscapes, other research and scientific evidence is required – and other books no doubt exist.

This text cannot be a guide to forest conservation in all nations, but it does highlight the vital role that forests – with their biodiversity, their intricately evolved food webs, and their special local relationship with weather, animals and soil – play in stabilising temperatures and rainfall.

Wohlleben is scathing in his assessment of the understanding that foresters and politicians have for the true value of native, old growth trees and forests. He writes: ‘When it comes to climate change, many foresters still think of trees as little more than biological storage units for carbon dioxide either while they are alive or, better yet, when they are dead… The living and breathing entity that is a forest is reduced to a vault full of carbon, its effects on global water and temperature management ignored.’

Wohlleben is pulling no punches. He eviscerates the German forestry industry with one example after another, from the disastrous practice of removing dead or dying trees to the economic claims of the value of plantations over forests. His writing is carried along by a sense of urgency: ‘Trees are key to slowing down climate change, and right now forestry is having a negative impact on two-thirds of the world’s forests.’ Wohlleben invites us to join his clarion call to stop logging, get out of the way of forests, and protect what remains.

Read: Book review: Eta Draconis, Brendan Ritchie

In his chapter highlighting the role of wolves as apex predators in preserving the forest, Wohlleben writes: ‘We can come at protecting forests from whatever direction we want, but the results are always the same. We must exert less pressure on nature by exploiting it less. We must strengthen forests by allowing them to take care of themselves.’ Science, wisdom and a call to arms.

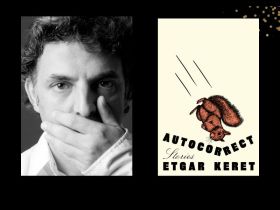

The Power of Trees, Peter Wohlleben

Publisher: Black Inc

ISBN: 9781760643621

Format: Paperback

Pages: 288pp

RRP: $34.99

Release Date: 18 April 2023