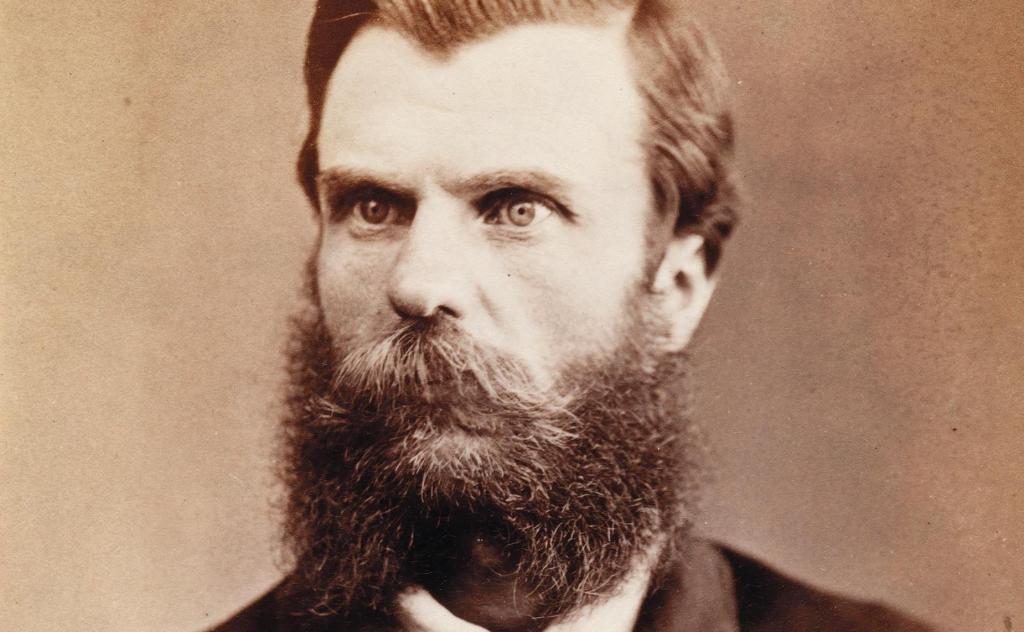

Described by author Garry Linnell as ‘an accidental bushranger and probably the unlikeliest of bushrangers that we ever saw in the 19th century in Australia,’ Captain Moonlite – aka Andrew George Scott – once was front page news throughout the country.

Today, Moonlite’s notoriety has largely been overshadowed by the legends which sprang up around his contemporary, Ned Kelly, as well as the deeds of other bushrangers of the day.

‘He and Ned Kelly were executed within 10 months of each other … [and their deaths] brought about the end of the entire bushranging era,’ said Linnell.

He believes that Scott, who was executed in January 1880, was deliberately written out of the historical narrative.

‘I think the nature of the man and his relationship with a young man called James Nesbitt, back in 1879, probably meant that a lot of the historians wanted to airbrush him out of the pages of history – because we’re talking about the Victorian era, a time of very prim and what they would call “proper” attitudes towards sexuality,’ Linnell explained.

Those attempts were not entirely successful, but it’s certainly true that Moonlite is less well known today than the likes of the Kelly Gang, Ben Hall and ‘Mad Dog’ Morgan, whose stories have inspired films and television programs as well as popular songs in their day.

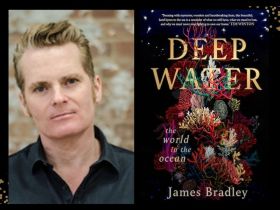

Linnell’s new book, Moonlite: The Tragic Love Story of Captain Moonlite and the Bloody End of the Bushrangers draws upon a range of primary sources – including a variety of newspaper accounts – to document the story of Andrew George Scott and James Nesbit.

‘When you go through the newspapers of the time – because they’re obviously a very important source in this story – it’s never quite openly said what sort of relationship the two men had except that it was close or that they were “inseparable”,’ he explains.

‘But when you read between the lines and you read some of the letters that some people wrote to the newspapers, it’s clear; there’s a “nudge nudge, wink wink” [tone]. There are references to James Nesbitt being a “puff”, which was a slang term back in the 19th century for homosexual men. So it was clear that a lot of people knew the full story of these two men; it was truly the love that dare not speak its name in public.’

‘It was truly the love that dare not speak its name in public.’

One of the reasons why we know so much about the relationship between Scott and Nesbitt, who first met one another in Melbourne’s Pentridge Prison, is because of a series of letters Scott wrote from his cell at Sydney’s Darlinghurst Gaol (now home to the National Art School) following his arrest – as well as several eyewitnesses.

In November 1879, Nesbitt was killed during a shoot-out with mounted troopers near Gundagai, and Moonlite was captured.

‘James had been shot in the temple by a trooper’s gun and as he lay dying, Moonlite leant over him and cradled him in his arms and – according to the other troopers who are watching this – kissed him passionately all over his blood-smeared face, and it was as though he was trying to breathe life back into him, and he was crying,’ Linnell said.

‘Then in the lead up to his execution, he sat in his death cell and wrote dozens of letters. He wrote to James Nesbitt’s mother and told her about his great love for James; he told other people too that he wanted to be buried with James, he wanted to share a grave with him and sleep with him for eternity. Now in the language of those days men often wrote to each other and declared their love for each other, but not with a sort of ardour and passion that we saw from the pen of Captain Moonlite.’

Writing from his cell, Scott wrote: ‘My dying wish is to be buried beside my beloved James Nesbitt, the man with whom I was united by every tie which could bind human friendship, we were one in hopes, in heart and soul and this unity lasted until he died in my arms.’

WRITING HISTORY WITH FLAIR

Linnell’s approach to writing Moonlite was to approach it almost like a novel in order to ensure the book’s accessibility.

‘I’ve tried to write it as a novel but it’s all true. There’s nothing that’s made up in there. Every quote in there is sourced – either transcripts in court cases or from arrest sheets and in newspaper reports of the time. I’ve written in the present tense because I wanted to make it interesting to people who normally wouldn’t pick up a history book because I find that footnotes slow the pace down … they also distract the reader from the momentum of the story you’re trying to tell.’

Viewing historical lives through a contemporary lens is a fraught process, but Linnell is adamant that Nesbitt and Moonlite were indeed lovers – a position which is supported by many Australian historians.

‘I think it’s one of the great love stories and I don’t want to see a story about so called bushrangers written – and I certainly don’t want to write it – without exploring the personal side of their lives, and the emotional side of their lives,’ Linnell said.

Garry Linnell’s Moonlite: The Tragic Love Story of Captain Moonlite and the Bloody End of the Bushrangers is out now through Penguin Books.