Brisbane writer/director Sue Rider and NZ-based writer/performer Helen Moulder had been working on their play The Bicycle and the Butcher’s Daughter for two years just before COVID hit in the lead-up to its launch in July.

‘First we lost our venue due to earthquake strengthening and then COVID-19 struck,’ said Rider. ‘We had nowhere to perform and didn’t even know if we would be in the same country. But we decided to scale down and go ahead whatever happened. We even joked that we could always rehearse on Zoom.’

That joke became a reality as restrictions due to COVID became tighter. Although Moulder was able to find a new venue in the shopfront of an old pharmacy in Nelson, it became apparent that Rider would not be able to travel from Australia to direct the production.

Determined to stage the play no matter what, the pair had to grapple with Zoom, a platform built for conference calls but not designed for directing theatre productions. One of the first things Rider did was build a model box of the set and work out the dimensions of the new space.

‘When you’re looking at something on Zoom, it is flat, it’s two dimensional and you don’t have any sense of distance,’ she tells ArtsHub.

This became a challenge when working out how to direct Moulder, which often made for a humorous exchange over Zoom. ‘Because I was in the place of the audience I couldn’t see the chairs and I had to kind of guess and was guessing a bit too far back and Helen kept saying “No If I go that far I am treading on somebody’s foot.”’

While directing one person over Zoom may be manageable, how do you cope with managing multiple cast members?

Filmmaker and theatre director Nicky Tyndale-Biscoe is currently directing The Street’s production of Barren Ground, a contemporary exploration of the asylum seeker experience in Australia which merges elements of the plot, dialogue and characters of Shakespeare’s The Tempest with media reports of and firsthand accounts of refugees.

She’s currently enduring Melbourne’s lockdown restrictions and is working with a cast of four actors based in VIC, NSW and the ACT to direct the rehearsals over Zoom.

‘I’m really interested in what Zoom and new screen based technology can offer artists in lockdown,’ she tells ArtsHub.

She said her background as a filmmaker has been advantageous when turning her hand to direct a play over Zoom. ‘I suppose filmmakers instinctively understand the frame rather than the proscenium arch space. So we automatically think, “Okay, what am I framing out? What am I focusing the viewers’ attention on? They can’t look at the whole space.”’

Actor William Tran during the creative development of Barren Ground. Image supplied.

Zooming in for creative effect

For directors working with Zoom for the first time, Tyndale-Biscoe suggests familiarising yourself with its many features before you get started. Like the breakout room, which is not only useful for rehearsals when actors want to go over lines separately but can also be used to creatively structure a virtual performance.

‘There are interactive possibilities in the way that you can use a breakout room for a performance; half the audience can follow two characters one way and the other half of the audience can follow another two actors, and then you come back together into the same space. I think that’s really fun,’ she said.

Read: On the precipice: theatre for the isolated audience

Both Rider and Tyndale-Biscoe both admit one of the big advantages of directing over Zoom is the ability to pick up subtlety, facial expressions and nuances in vocal tone.

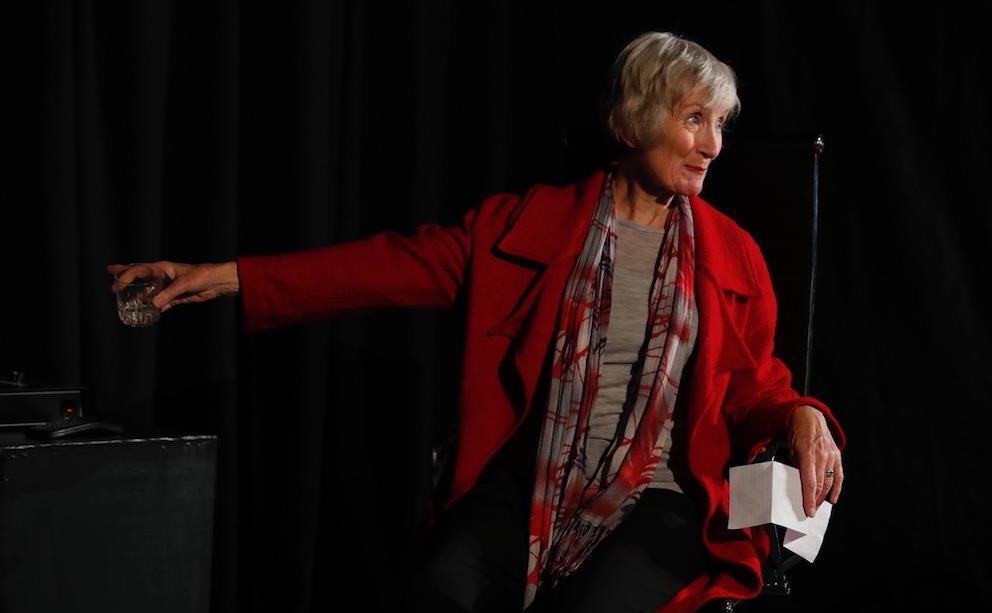

This rung particularly true for The Bicycle and the Butcher’s Daughter, a one woman show about family, global food issues and fake news which sees Moulder play five characters displaying a breadth of emotions with characters ranging in age from 11 to 93.

‘When you’re in an actual space, you’re never close up to an actor, you’re always seeing them in the largest space on the stage,’ Rider said. ‘When she [Helen] was very close up, I could see all that subtlety and the changes in her face. And I think that was really good for her too, because she could communicate with me and see my reaction, which was very valuable.’

This also resonates for Tyndale-Biscoe who is using techniques from her filmmaking background for creative effect and close-ups on Zoom’s platform.

‘You can use depth of field as you would in film with a frame and you can get actors to go right up to their cameras and whisper. They can really use volume in different ways too,’ she said.

Overcoming challenges

Unlike directing in a physical space where the actor and director can see and hear the exchange going on in real time, problems can occur over Zoom if the internet connection is unstable. When attempting to correct Moulder during rehearsals, Rider sometimes noticed a delay in communication and by the time her directions came through, Moulder had already moved forward with the script.

‘I think it was quite disconcerting for her, which was difficult. So I had to learn to kind of hold back a bit until there was a decent little moment where she didn’t say anything. And then I’d say, “Let’s stop now. Just go back over that.”‘

This went for comic timing too.

‘I had to learn not to laugh at the funny bits. So she was getting no feedback there. But it was actually better because if I did laugh, it wouldn’t register until after she had said the line anyway.’

Another challenge for those new to directing via Zoom can be instructing the actors where to look. Tyndale-Biscoe said this can be more difficult for people used to working exclusively in theatre because it’s more natural to look down the barrel of the camera where the audience is.

‘Definitely play around with all the different view functions and make sure you’re really on top of who’s seeing whom and in what way, because that will affect eye lines and eye lines are something that you need to be conscious of while directing,’ she emphasised. ‘If you get this wrong, actors won’t look like they’re looking at each other.’

Because performance is so much about audience reaction and participation, it’s still imperative to have feedback even if the production you’re directing is being done virtually.

In the case of The Bicycle and the Butcher’s Daughter Moulder decided to open up rehearsals to the public to get as much feedback as possible in the lead up to the final week’s rehearsals when Kiwi director Giles Burton came on board to help.

‘Helen would ask questions and get feedback from the audience, which actually fed into what adjustments we did make because it was valuable having an audience in there so we could hear what their reactions were. And we could tell whether we were on the right track or not.’

The decision was the right one because since the production opened it’s been selling out (to a socially distanced crowd), and will extend into September once the most recent COVID restrictions in NZ are lifted.

Although she couldn’t attend in person, Rider has been been present over Zoom.

‘I wasn’t there on opening night because we didn’t want Helen to have the added complication of having to set me up on Zoom on a laptop somewhere. But I was present for the preview and have since been watching once a week.’

Barren Ground will also throw its virtual doors open next week to invite audiences to watch the work in progress. The production was initially to be staged in front of a live audience once complete, but since Melbourne faces the potential of a further state of emergency it’s now being rehearsed for a Zoom audience too. Tyndale-Biscoe is happy to take on the challenge.

‘This might be the way theatre is is delivered for quite a while, so let’s embrace the medium and explore it,’ she concluded.