Artist, designer, educator, curator and arts leader Dr Laurens Tan died in Las Vegas (US) on 20 January, having forged a legacy and influence admired and appreciated by many. He was 74.

Active as an artist since the 1980s, Tan was a member of an important generation of Chinese diaspora artists in Australia who came to local and international prominence in the 1990s. He created works in multiple mediums, beginning with ceramics as a fine arts student, before extending to sculpture, animation, video, 3D graphics and music, becoming increasingly interdisciplinary by utilising his training in architectural and industrial design as his practice developed over four decades.

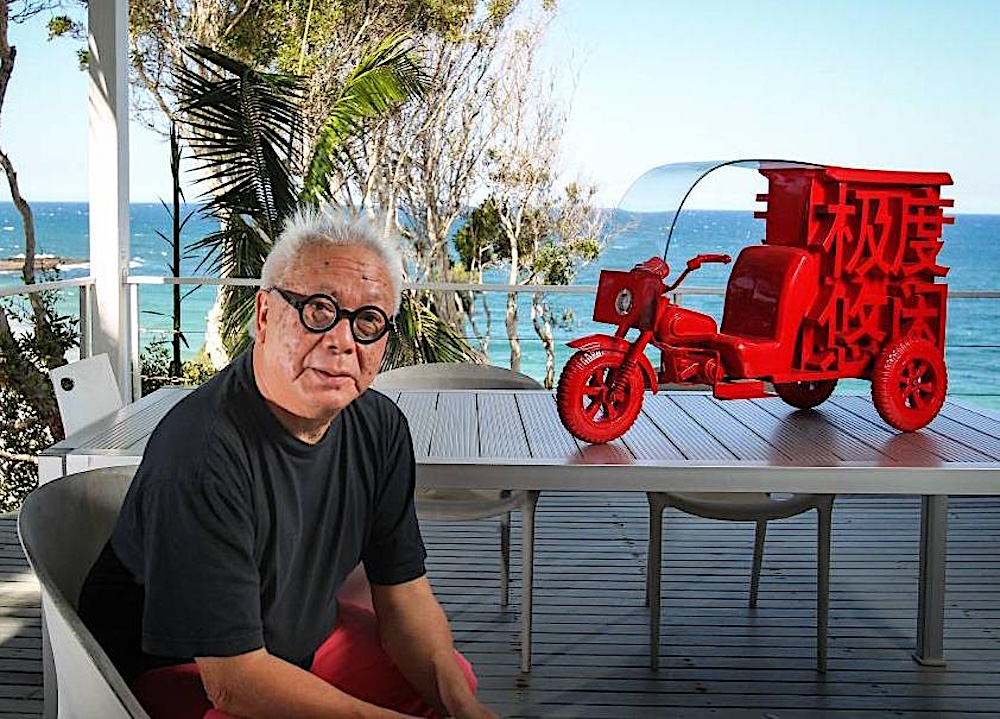

He is best known for his intricately fabricated and assembled sculptures, made of fibreglass and finished in baked enamel. Combining visually striking proletarian and pop culture forms, they investigated an interplay between language, culture and capital in a globalised world.

Significantly, Tan’s connection to Europe and Southeast Asia in his early life shaped his identity and artistic practice, which in turn encouraged expanded notions of ‘Chinese-ness’ in Australian art and cultural discourse – a label that, paradoxically, constricted an individual’s right to complexity, yet helped connect and communicate with audiences, here and abroad.

Powerhouse Chief Executive Lisa Havilah‘s connection with Tan goes back to the late 1980s, when he was teaching in the Creative Arts department at the University of Wollongong (1987–1991). She reflects that it was his “restless energy that took him around the world, to restless cities, to Beijing, to Las Vegas and always back home to the cliff edge restless ocean landscapes of Wombarra,” she says.

“Laurens chased risk, considered risk for all its potential rewards and all that you could lose from chasing it. He didn’t lose often, and it became the central thesis of his practice as he pushed out, against and forward.”

Capturing the sentiment that many felt towards Tan, Havilah continues, “I first met Laurens when I arrived at art school. I couldn’t believe how much he was in and ‘of’ the world. He led many revolutions across the many institutions that tried to slow him down, using up their international admin budgets in a single week. It was compelling to all that got to be part of it.”

Gary Carsley, Artist and Honorary Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Arts, Architecture and Design, University of New South Wales, adds: “Laurens was a man with a robust appetite for those things in life that are expressions of connoisseurship, not mere curiosity. Warm and generous, Laurens was generationally consequent for the contributions he made to our community. His is an inextinguishable light.”

Understanding Laurens Tan and his global ecology

Laurens Tan lived a truly peripatetic creative life. As equally as he embraced his life at Wombarra, on the beautiful Illawarra South Coast, just beyond Sydney, he also maintained a studio in Beijing, China and a base in Las Vegas (US) from the mid-2000s on.

“Laurens was always surrounded by an ecology of people – crazy, skilled people that moved in and out of his orbit depending on what the latest project was. All of us committed to his latest vision,” Havilah tells ArtsHub. “I was lucky to be one of those people, always compelled to see what was going to happen next. I picture Laurens in front of every generation of Apple computer, the screen getting bigger, like a halo, in the darkness, the ocean loud outside, the next deadline in a different time zone only hours away.”

Tan was born in 1950 in The Hague, the Netherlands, to parents of Chinese-Indonesian descent. His grandparents emigrated from Fujian province to the Netherlands in the late 19th century. Following his early years in Europe, Tan’s family lived in Surabaya, Indonesia and Singapore, before migrating to Australia in 1962, when he was 12 years old.

Looking to pursue an education and career in art, Tan was initially discouraged by his career-academic father, who regarded the fine arts as providing lacklustre career opportunities. After studying music theory and arrangement at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music in 1972, Tan relocated to Adelaide, disregarded his father’s advice and enrolled at the University of South Australia in a Bachelor of Education (Fine Arts), which he completed in 1978.

He followed this up, almost a decade later, with his first foray in China, studying Cultural Studies in the School of Architecture at Hunan Normal University, Changsha, in Hunan province.

Speaking with The Stand, Tan once confessed: “My Chinese heritage was obscured by travelling so much elsewhere. I went to China for the first time in 1987, and that was interesting: people were calling me ‘brother’, even though I spoke not a word of Chinese. That had a strange effect on me, given the obscurity of my heritage.”

While consistently making and exhibiting work, upon his return to Sydney, Tan took up academic posts as Lecturer in Creative Arts at the University of Wollongong (1987–1991), Lecturer in Drawing for Ceramics at Sydney College of the Arts (1987–1993) and Lecturer, School of Design, at University of Western Sydney (1992–2003), among subsequent posts. He also lectured in later years in Nevada, in the US.

Perpetually intellectually hungry, Tan completed a Master of Creative Arts at the University of Wollongong in 1991 before rounding out a life-long education with a PhD at the University of Technology Sydney in 2005. His thesis, titled, The Architecture of Risk, deconstructed the built environment of Las Vegas, where he was later to establish a home base.

Dr Daniel Mudie Cunningham, Artist and Curator/Director, Wollongong Art Gallery, recalls, “I was fortunate to teach alongside Laurens in the design school at Western Sydney University in the early 2000s and, like many who came into his orbit, was a recipient of his warmth and wisdom, and witness to his powers as a visionary artist and thinker. Simply put, Laurens made the art world a better place.

“I was looking forward to working with him again after selecting him for Cementa 2024. Laurens undertook a residency in Kandos, but received his cancer diagnosis soon after and withdrew to focus on recovery. He had planned to partner with the local bakery to create a special batch of Cementa moon cakes, to extend Sydney’s concurrent Moon Festival into the regions. Though his Kandos moon cakes were unrealised, they are conceptual evidence of his generosity of spirit and commitment to cultural exchange. Infinitely unpretentious and playful, Laurens’ contribution to my ongoing Funeral Songs project was the ’80s Aussie rock track by James Reyne, ‘Heaven on a Stick’,” adds Cunningham.

Riding the China boom

While establishing himself in Beijing during the mid-2000s ‘China boom’ in contemporary art, Tan forged connections with contemporaries and a broader international audience. He exhibited his works at numerous galleries in Beijing’s 798 Art Zone, including his 2008 commissioned work within his wider Babalogic series that was curated by internationally renowned Chinese curator Wu Hung, alongside works by peers including Shen Shaomin, Miao Xiaochun and Qiu Zhijie among others.

Building on this exposure, Tan was invited to participate in group exhibitions further afield – in Beijing, Guangzhou, Taipei, Seoul, Vancouver, New York, Miami and Las Vegas – over subsequent years.

Sitting down with arts writer and curator Luise Guest in 2013, for a conversation published in The Art Life, Tan said: “After six years in Beijing I needed a new or an additional stimulus. I went to the US four times in the space of 18 months. I had thought of buying a house in Vegas twice before. I didn’t go there because of art! Vegas is calming, like a hideout. I’m in solitude there. In Beijing you’re in the traffic, which facilitates ideas and projects, but Vegas is more like a void. It’s like the opposite of Beijing. Beijing, it’s a love/hate thing. In Beijing it’s quite clear, I get quite frustrated with the non-logical manner of how things work or don’t work and the chaos. The love part is also quite clear – the Chinese language has such depth, and I don’t think I could ever find that anywhere else. I’ve got a bit of a handle on that now, extracting possibilities.”

Following the news of Tan’s death, Guest adds to ArtsHub: “I crossed paths often, over many years, with Laurens Tan in the small art world enclave of Chinese and China-focused artists, writers, curators and critics, but it wasn’t until 2013 (oddly enough the last Year of the Snake before this one) that we sat down together to record that interview for The Art Life. We covered a lot of ground: about art and life, the difficulty of learning Mandarin, his work as a teacher and mentor to young artists, and his idea that art is ‘a vehicle for thinking’ – literally, in the case of his series based on the iconic Beijing san lun che, or three-wheeled vehicle. That turned out to be the first of many conversations, in Sydney and in Beijing.”

Guest continues: “Laurens was generous, kind, full of great stories, and endlessly curious about the world and its possibilities. At the end of that first conversation, I asked Laurens: ‘Is the artist inevitably a gambler?’ His reply: ‘The simple answer must be yes. I mean, there are different ways of operating as an artist, but essentially I think art is always about embracing risk and letting go. And that’s the hardest part’.”

Tan’s first decade in China was additionally supported by multiple artist-in-residency programs and research grants he was awarded, including from the Australia China Council (2006–2007) and the Australia China Art Foundation (2014).

A life in exhibitions

Closer to his home in the NSW capital, Tan was commissioned by the City of Sydney for large-scale sculptures that were presented as part of the Lunar New Year festivities in 2016 and 2019.

His works have been exhibited widely in Australia and at institutions internationally, including Banff Centre for the Arts, Canada; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Today Art Museum, Beijing; and Shizuoka Prefectural Art Museum, Japan. His works are held in public and private collections in Australia, China, Japan, the USA, Canada, France, Germany, Switzerland and the Netherlands.

A galvanising force among his artistic community, especially in Sydney, Tan was also known to bring artists, their works and audiences together as a curator. His curated exhibitions include, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? (2000) for Project Contemporary Art Space, Wollongong, 4A, Sydney; and Casula Powerhouse Arts Centre, NSW, that included works by Shen Jiawei, Fan Dongwang, Jiyang Jin, Aaron Seeto, Savanhdary Vongpoothorn, Ngoc Tran, Tom Dion, Lan Wang, Ying Guo and Tiffany Lee-Shoy. Another key exhibition was Arena – A Post Boom Beijing (2010) for Hazelhurst Arts Centre, Sydney and touring to La Trobe University, Bendigo and James Cook University, Townsville.

Aaron Seeto, former Director of 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art and now Deputy Director, Hirschhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Museum, Washington DC in the US, also shares deep ties with Tan. “Laurens was one of the first professional artists I met as an undergraduate student at the University of Wollongong. His generosity opened up a network of friends and supporters who welcomed me into the world of art.

“As a young artist still in art school, it was unexpected for someone so experienced to show interest in my work, but Laurens did just that. He included me in my first major project, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, which introduced me to new circles of friends and diverse perspectives on the complex Asian Australian identity politics of the early 2000s. This experience revealed the various ways artists can engage with the world – as creators, curators, organisers and provocateurs.

“His friendship came during a crucial and formative period in my development. Dinners at various suburban Chinese restaurants in Wollongong fostered new friendships and immersed me in the vibrant local art scene – relationships that propelled me into the work I am currently doing. For all of this, I am deeply grateful,” Seeto tells ArtsHub.

“Laurens had a great, unwavering belief in what people can create together,” Dr Mikala Tai, Head of Visual Arts, Creative Australia, adds. “Always an early adopter, he sought out new thinking and people; he delighted in the collision of ideas that subsequently emerged. Laurens was also kind and generous – as he was to all young Asian-Australians trying to navigate the art world. I will be forever indebted to him for his guidance and counsel.”

Tan’s leadership was demonstrated in governance and advisory appointments as a Board member of Gallery 4A (now 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, 1997–2007), Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, artist advisory group member (2004–2006), and Board member of Wollongong Art Gallery (2006–2008).

If curated exhibitions were primarily for the benefit of general audiences, then the luncheons hosted by Laurens and Vivian [Vidulich] at their home in the Illawarra were more personal offerings to their community.

Perhaps hundreds of artists, curators, writers, collectors and interesting people from all walks of life were invited by them to convivial gatherings over decades that brought people together and forged many friendships.

The writers’ personal reflections

Pedro de Almeida: “I first met Laurens at Campbelltown Arts Centre in 2005 when his work was awarded the Fisher’s Ghost Art Award. Just who is this man with Le Corbusier-style specs and shock of white spiky hair? Over the years I got to know Laurens and his partner Vivian better, as they attended pretty much every exhibition opening I would turn up to and we fell into conversation, such was their unmatched dedication to friends and their shows – it seemed they were friends with everyone.

“Later, when I worked at 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art I was pleased to learn of the massive contribution Laurens made there as a foundational Board member and discover some slides in the archive of early fundraisers over Chinatown banquets, Laurens and Vivian captured in high spirits with (gulp) a special performance by Kamahl!

“Befitting a man who lived large across three continents, I was never that surprised when I would discover some little ‘secrets’ about Laurens, such as the fact that he was a world class blackjack player, known and respected on the Vegas circuit, or that he was an avid collector of vintage Japanese toys. Yes, Laurens’ contribution to Australian art was significant, but more than anything, Laurens and Vivian represented for me the standard bearers of what a love for art and each other could be.”

Gina Fairley: “Similarly, I fondly remember Laurens stepping off a plane in San Francisco, US, and heading straight to the gallery where I was working, with the familiar greeting, ‘Hey Gina, can I use your fax machine?’ We all said ‘yes’ to Laurens. He had a tireless energy for the next project, the new connection, the beckoning frontier – and it was totally infectious.

“Some 26 years later, I was excited to be plotting to connect with Laurens in Las Vegas on another bold project, embracing new frontiers in art and technology. In his signature way, he was a master at pulling things off. That tenacity – that laugh, never sitting still – you will be missed my many, Laurens.”

A tale of three cities

Despite working in Beijing and Las Vegas, two cities that could not be more different in their historical myths and present-day social realties, Tan never looked more at home then when hosting friends with wine and oysters on the balcony of his and Vivian’s home overlooking the Pacific Ocean.

Since the mid-2000s Tan lived and worked across three bases where he kept homes and studios: Wollongong, Las Vegas and Beijing.

Laurens Tan (7 August 1950 – 20 January 2025) is survived by his wife Vivian, children Jacinda and Michael, and siblings Charlotte and John.