An initiative that started in 2010, #AskACurator was the brainchild of Jim Richardson, founder of MuseumNext, a conference on the future of our cultural institutions. The one-day event was designed to usurp the bland marketing messages of institutions and to put real questions to real faces.

While the idea started harnessing Twitter’s networking power, it has since moved on to embrace multiple platforms. A decade on, ArtsHub has posed 20 questions to 20 curators nationally.

Q: How often does the plan on paper match the eventual hang in the exhibition space?

A: Kelly Gellatly: Director, Ian Potter Museum of Art, University of Melbourne (VIC).

I think it is different for different curators. I am a very visual thinker so, as I am working on a show and as works fall in and out of that final decision making, I think about what I am trying to convey in the narrative of a show visually, and I start that journey through the space.

It took me a while to realise that so many curators don’t do that – some only have a vague idea – but for me it is a very concrete, tangible way to work. I have always felt that an experience of an exhibition is an emotional and visceral one first, and then an intellectual one.

Q: What is the greatest challenge for a curator taking Australian artists abroad?

A: Professor Natalie King OAM, independent curator and, Curator of New Zealand Pavilion at 59th Venice Biennale 2022 (VIC).

Australian artists are highly adaptive, talented and capable of working in provisional situations alongside their international peers. In my experience, there are two significant challenges. Firstly, State and Federal governments need to strategically align their priorities and provide a joint vision for international alliances with a correlation of creative objectives. Otherwise, the approach will continue to be haphazard.

Secondly, sustainability is vital. For example, an artist who exhibits at documenta needs ongoing support and opportunities, or an artist in the Jakarta Biennale needs a sustained presence. We need to work collectively to ensure that artists have careers of longevity with international outcomes.

Q: How do you find new artists, new ideas as a curator?

A: Hetti Perkins, Curator 4th National Indigenous Triennial (2021), National Gallery of Australia (NSW & ACT).

Luckily for me, new ideas and new artists seem to find their own way! While there is a level of research involved, more often than not it is an organic process. Like seedlings, new ideas make their way to the surface – mostly against the odds – and by keeping your eyes and ears open all a curator has to do is maybe help them along and watch them flourish! As the inheritors of the world’s oldest continuous culture, Aboriginal artists are part of a diverse tradition that has survived and thrived because it is at once old and new, of the past, in the present and for the future. Always has, always will be.

Q: How intuitive is it for a curator to have a good spatial read, or is it something that comes with experience?

A: Daniel Mudie Cunningham, Director of Programs, Carriageworks (NSW)

Grasping spatial dynamics as a curator involves a mix of intuition and experience, combined with a responsiveness to the history and purpose of place. Conventional ‘white cube’ spaces have different demands to repurposed sites not originally intended for art.

In recent years my work has been either exhibitions at the former railyards of Carriageworks or permanent public artworks on the other side of the tracks at South Eveleigh (formerly Australian Technology Park). Working at scale and in response to the Indigenous and industrial heritage, a more successful outcome arises from understanding how space and place is negotiated in tandem.

Q: How much is too little, and how much is too much when it comes to information in the exhibition space?

A: Dr. Anthea Gunn: Senior Curator of Art, Australian War Memorial (ACT)

By the time I’m writing exhibition text I’m usually overflowing with Exciting Facts so it is hard to not write an essay. My rule of thumb is that artists communicate with viewers through their work, so what does the viewer need to know to have that conversation? But not interrupt them with unnecessary detail?

To manage this I go back to the core purpose of the exhibition. For example, in Australian War Memorial exhibitions the historical context is important: was the artist a soldier? An eyewitness? Who or what is the subject? A visitor needs these details to understand the work. But for the same piece exhibited in an art historical survey, the development of their style and artistic influences may be more relevant.

Read: So you want my arts job: Mona Curator

Q: Do people understand what curators do?

A: Micheal Do: Curator Contemporary Art, Sydney Opera House (NSW)

The term curator has become so ubiquitous, I sometimes wonder whether it’s been hollowed out of all meaning to the detriment of professionals and artists. Personally, I believe the term (like all labels) is less significant than the individual themselves. It’s a question of hard-won, deep knowledge and expertise. How has a curatorial project been developed? Can they articulate the complexity of artists’ practices without shoehorning random ideas? What types of skills, networks and knowledge sets have they developed with time?

These questions speak to a curator’s credibility and legitimacy as both a selector of artists’ work and their role as a creator of timely, mysterious and (my personal favourite) haunting exhibitions. Otherwise, aren’t we all just glorified Pinterest users?

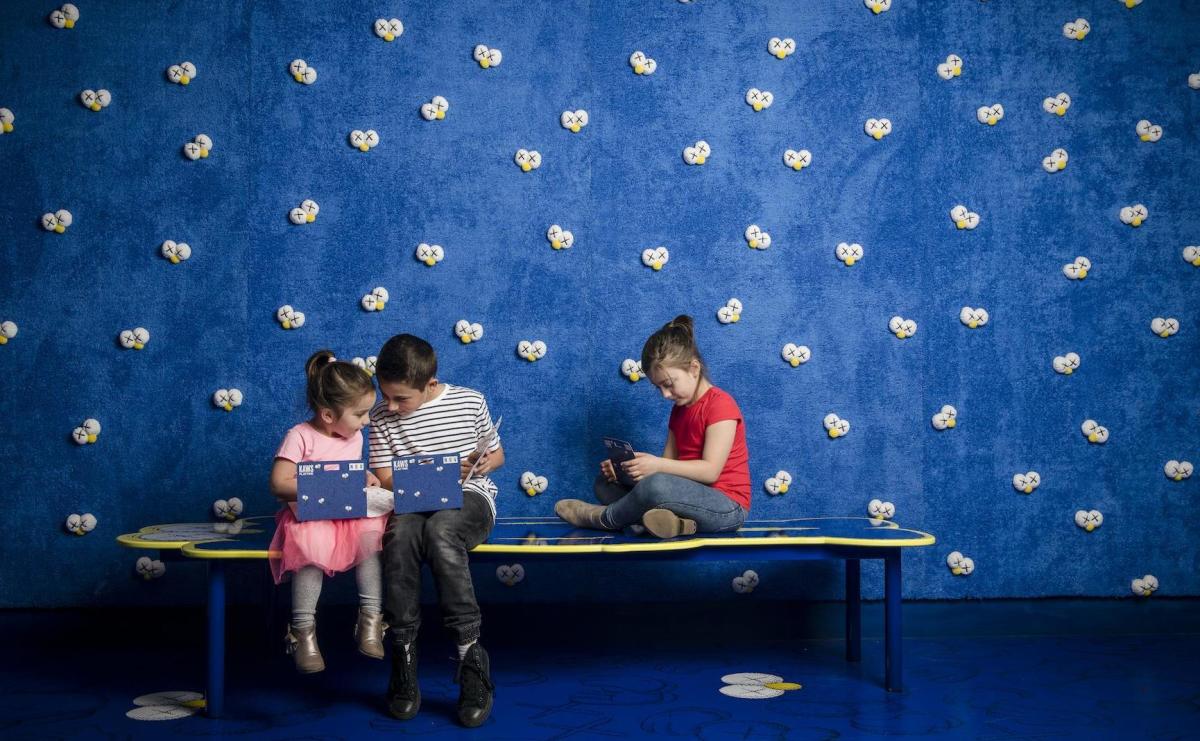

Children playing inside KAWS: PLAYTIME at NGV International. Photo © Eugene Hyland

Q: What is the key thing to consider when curating bespoke kids exhibitions?

A: Kate Ryan: Curator of Children’s Programs, National Gallery of Victoria (VIC)

NGV’s children’s exhibitions are curated to be exciting, fun and full of surprises for our youngest visitors. The exhibitions are developed in collaboration with contemporary artists and designers, and together we work towards presenting an exhibition that is a rich learning experience accompanied by a range of activities inspired by the artist’s ideas and methods of working.

A consideration during the developmental phase is to never assume we know how children will respond to an activity – the last thing we want is for our young visitors to be bored! So we include them in the process and conduct activity trials at primary schools. This is where we observe how children interpret concepts, sense their excitement for ideas and take in feedback. We rely on the children’s responses to help us deliver an accessible, relevant and engaging program of exhibitions for all children to enjoy.

Q: Is it a good idea to look outside the mega city centres to develop your curatorial career?

A: Dallas Gold. Founding director and curator, Raft Artspace (NT)

My simple answer is a resounding Yes, of course. I would go as far as to say it is imperative. Contemporary art does exist outside the major population centres! Regional and remote Australia is where a lot of significant art is produced and there are also opportunities for curators.

I would recommend looking outside the city to engage with Aboriginal artists and the conversations that happen on the fringe. Curators absolutely need to look outside of the city to gain a full perspective of what is happening in this country in order to further enrich their practice.

Q: Do curators have an ethical and / or social responsibility?

A: Bruce Johnson McLean, Assistant Director, Indigenous Engagement, National Gallery of Australia (ACT)

Perhaps I’m biased, as I am part of a community that expects social and cultural responsibility be at the centre of your working and living ethos, but yes, I absolutely do believe that curators, programmers, managers and everyone involved in the arts sector have ethical and social responsibilities, plural.

These range from engaging in fair and ethical dealing with artists, maintaining the integrity of the artists voice in interpretation and not assimilating their voices into a curatorial agenda, through to ensuring exhibitions – historical and contemporary – are an accurate reflection of the times and communities we live in. A guiding ethics of truth and truthtelling should drive this work.

Q: Are galleries sites for activism and social justice and as a curator what is the greatest challenge in presenting ‘voice’?

A: Talia Linz: Curator, Artspace, and co-curator of the 2022 Biennal of Sydney (NSW)

Galleries and, more broadly, institutions and their programs certainly can be, and historically have been sites for activism and social justice on both sides of the equation. Institutional critique, relational aesthetics, social practice – and whatever the next contentious umbrella term will be – function with the tacit understanding that audiences always play active rather than passive roles.

In regards to presenting ‘voice’, it’s not a challenge per se, but rather something to be steered by, which is that every project is unique and different and requires a tailored, mutually respectful approach. Like any relationship, assumptions and expectations are probably best left behind.

A more recent development aligned with wider social change is that beyond providing important platforms for artists and audiences to engage in…increasingly they are being incorporated as integral components to the character and guiding principles of institutions themselves – hopefully beyond being reactionary or as pure tokenism.

Q. What is the greatest challenge of curating projects in non-conventional, non-gallery spaces?

A: Sebastian Goldspink: Curator 2022 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art, Art Gallery of South Australia (NSW)

Inherently, I’ve always seen these spaces as an opportunity rather than a challenge. That being said, I think it’s about resisting the urge to make the space look like a gallery, embrace the flaws and imperfection and the difference. These spaces come with a myriad of logistical obstacles to do with insurance and liability but if you can fight through all of those elements, they can produce impactful and memorable exhibitions.

Q: Are there practical tips or challenges as a curator, when working with a collective, and managing multiple expectations?

A: Nur Shkembi: Melbourne-based independent curator, writer and founding member of Muslim Australian collective, eleven (VIC)

I find that clear communication, as well as having a shared narrative or goal assists immensely with setting expectations for everyone involved. I rarely see this as managing, rather, this is a form of collaborating and providing the support to achieve an agreed vision.

I am also part of a collective of artists, curators and writers called eleven. Each of the members of the collective are incredible professionals, so we are not so much ‘managing’ the expectations of each other, rather we each contribute our part and work towards an agreed project outcome.

Q: Do Australian curators need to better work to better represent contemporary Australian society – is this part of their job?

A: Mikala Tai: Director, Centre for Contemporary Asian Art 4A (NSW)

Being a curator comes with responsibility. In fact, great responsibility. We play an active role in the creation of contemporary culture and, as culture belongs to everyone, it should reflect the complex and nuanced reality of contemporary Australia. All dimensions of society should be included and interrogated within our galleries and museums, sometimes these are tales of joy, other times they are politically punchy and often they are just plain silly. All of this is part of our lived culture and, as curators, we need to work hard to ensure that we are supporting the breadth and depth of contemporary cultural conversations.

Q: What is a good career trajectory path for a curator – where should I start and where should I aim?

A: Anthony Fitzpatrick, Curator, TarraWarra Museum of Art (VIC)

Every curator’s path is different and not always a straightforward one. I initially majored in Literature and Classics thinking I might pursue a career in museology or archaeology. But a career in visual art won out and the postgraduate Master of Art Curatorship and Conservation, University of Melbourne both provided many important opportunities to learn not just art history and theory, but the more practical, tangible aspects of exhibition making. During this time, I was fortunate to be mentored by Joanna Bosse, then Assistant Curator at the Potter Museum, during a 3-month internship where I gained invaluable insights into the multi-faceted role of the curator and the behind the scenes dynamics of a major art institution.

But experience with a small organisation, where I could really cut my teeth, first as a volunteer, then as Collection Manager at the Cunningham Dax Collection, was critical in gaining significant hands on experience in all aspects of the conservation and curation of artworks. Lessons and skills learned from this formative period continue to underpin my work today.

Q: How should an artist contact or approach a curator, and is that OK?

A: Sarah Wall: Curator, Perth Institute of Contemporary Art, WA

Of course! Although I appreciate this is not always an easy thing to do. I would advise against cold-calling or emailing unsolicited proposals – this can give the impression that an artist is sending out blanket feelers to lots of curators.

A personalised invitation to an opening or event is always a nice approach. Or if you have a mutual friend or contact – use that to your advantage and ask for an introduction. It’s important that when artists reach out they have some knowledge of the curator they’re approaching.

More generally, going to exhibition openings, talks, and other events can be a really natural way to meet curators.

Q. Why is it important for curators to be brave and lead in new thinking?

A: Jarrod Rawlins: Museum of Old and New Arts (TAS)

For me it is important to always aim for the complex and difficult. As a curator each time I work on an exhibition I need to learn something, if I am not learning something new then the audience is not learning something new, and I have never learnt anything from staring at the status quo. My job is not only to seek out the brave new ideas and aesthetics, but to create a way for the unfamiliar to seem familiar – this is when we learn together.

Q: Curatorial careers can often be very specialised. How bring that specialisation to a broader engagement?

A: Nina Earl: Assistant Curator, Powerhouse Museum (NSW)

Today’s understanding of health is changing rapidly, and we are seeing other knowledge systems being integrated into medical thinking. Working with the Powerhouse Museum’s medical collections means thinking about all the different ways we engage with health and medicine in society. My scientific background allows me to connect with scientists, engineers, and doctors from diverse backgrounds to understand how their work is creating new knowledge and products that improve our lives. This leads to incredible partnerships that create innovative new solutions to contemporary health challenges.

Our upcoming exhibition Design for Life looks at one of these cross overs showing lifesaving technologies that have been developed with designers, making them more accessible than ever.

Q: How important is it for a curator to think of alternate viewing experience when preparing a show?

A: Leigh Robb, Curator of Contemporary Art, Art Gallery of South Australia (SA)

The challenge and opportunity is how to create new intimacies with art at a distance. Curators need to be thinking of critical leaps that bridge the divide between a physical experience of an exhibition and its digital approximation.

Alternate viewing experiences will need to be programmed into the curatorial methodology from the outset. This is already becoming another channel or production that can draw from the catalogue, studio visits, public programs, education resources and documentation.

They need to be curated and not be misread as promotional content or advertising collateral… but [they] don’t need to overwhelm the audience.

It’s important that artists aren’t expected to provide free content.

Conversations with the artist at the outset will be key, building this into the exhibition invitation, asking how they want to be seen, heard, interpreted in this context; imagining a parallel micro-exhibition space or multiverse that explores and brings people closer to the intrinsic elements of the work.

In this transitional time, we shouldn’t second guess the artist or the audience. But equally, we shouldn’t expect them to do all the work. Curators and educators will be responsible for creating new meaningful formats, models and realms that amplify the integrity of the artists’ ideas and the power of the exhibition.

Follow the conversations online today, Wednesday 16 September for international #askacurator day.