A stage adaptation of the story of a brutalised young boy, mocked by his teachers and regularly beaten by his drunken father, seems – on the surface – an odd choice for a theatre company whose core demographics are families and children aged eight and over.

But Slingsby, based in Adelaide, specialise in ‘emotionally challenging and engaging storytelling … original theatre productions that captivate, challenge and inspire hope,’ and their latest work (produced in partnership with State Theatre Company SA) certainly lives up to that aspiration.

Though it delves into some dark and discomforting territory, The Boy Who Talked to Dogs is ultimately a redemptive tale about an abused boy who discovers an inner strength, and draws upon it in order to overcome adversity – helped along by his close connection with various canine friends.

Irish playwright Amy Conroy’s adaptation of Martin McKenna’s memoir dances nimbly between the grim realities of Martin’s life and the more traditional tropes of children’s theatre, with Martin (embodied by actor Bryan Burroughs, another Irish artist) demanding on several occasions that the story be told with his voice, in his own words – even going so far as to criticise the play’s title, suggesting ‘Runt’ as a more accurate alternative.

Later in the piece, in a foreshadowing of the real Martin McKenna’s eventual move to Australia as an adult, the theatrical version of Martin fights against the interjection of a jocular tone into the story, and here Conroy brings an outsider’s precise eye to her lyrical descriptions of Australian sunshine. Elsewhere, the script features references that will clearly resonate best with an Irish audience (the production is eventually intended to tour Ireland once international travel has resumed) such as a memorable description of two grim characters having faces like ‘January mist and Irish grammar’.

Read: The art of the impossible: International collaboration during COVID

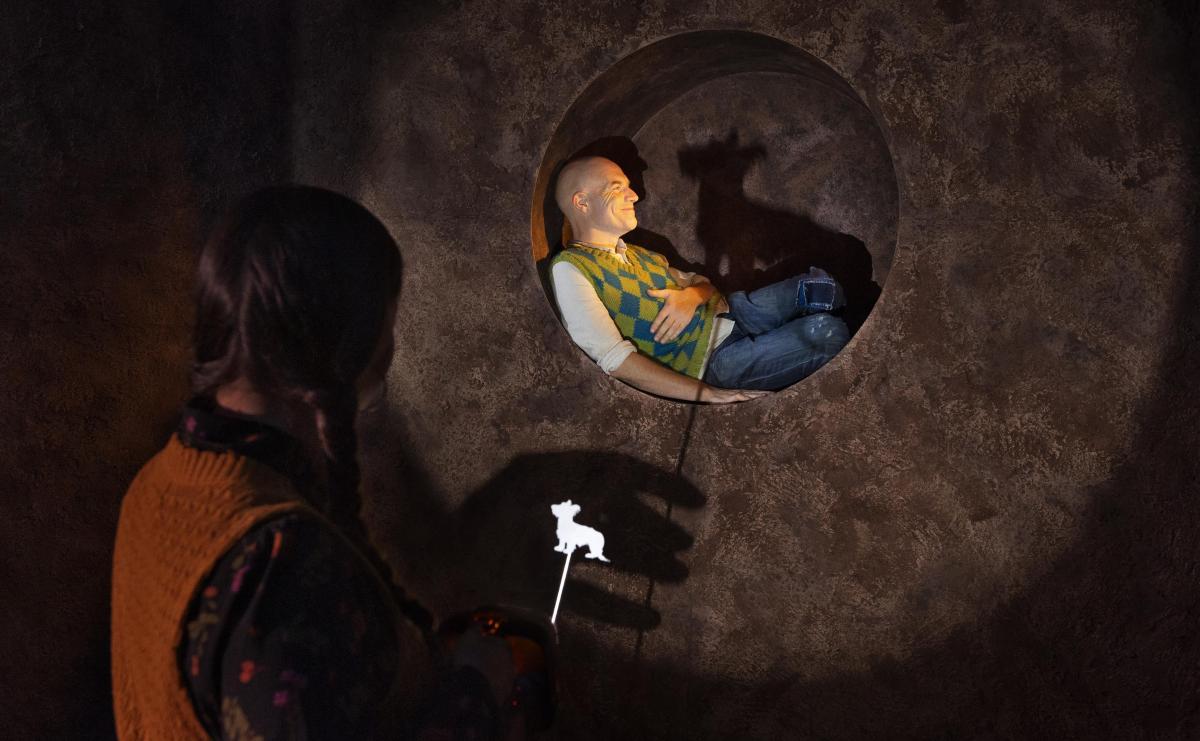

Demonstrating that the simplest theatrical tricks can often be the most magical, the production utilises basic shadow puppetry and projection to sometimes devastating effect, such as scene in which the young Martin has been bashed by his father and locked in the coal shed with the family dogs.

Martin, we learn, is an uncontrollable child. ‘It’s like my body can’t listen to my brain and my brain can’t listen to my body and they’re screaming at each other all the time and it’s so loud that I can’t hear either of them,’ he explains. Today he would be diagnosed with ADHD, but in 1970s Ireland there is no diagnosis, no treatment, only bullying, belittling, humiliation and abuse.

The presence of his protectors, the family’s German shepherds Rex and Major, soothes Martin’s racing brain, his racing heart. ‘Why are you the only ones who understand me?’ he asks. ‘Do you speak my language? Or do I speak yours?’

The violence which punctuates Martin’s life is generally mimed or implied rather than embodied; we hear the smashing of glass instead of seeing it, and when the boy is dragged outside, it’s a stool that bumps down the stairs to the coal shed rather than the actor himself. Nonetheless, some moments are confronting even for adult audiences (this reviewer wept more than once during the performance – sometimes with joy) and the play itself is recommended for children aged 12 and over.

‘The simplest theatrical tricks can often be the most magical…’

A three-piece band lead by Victoria Falconer as the MC-like character Muso opens the performance and plays live throughout, including new songs by Irish singer Lisa O’Neill (which expand on the world of the play and add further colour and shading to the story, as opposed to directly advancing the plot as they might in traditional musical theatre) but the focus throughout is on Burroughs, who plays every character – Martin himself, his mammy and da, and also the boy’s teachers and tormentors.

Immersing himself in the role from the moment we see him – cowed but not broken – Burroughs is simply superb, giving a committed, convincing, intensely physical and emotionally raw performance.

Other aspects of the production, such as the vivid washes of colour by lighting designer Chris Petridis used to evoke Martin’s sugar high after an illicit late-night feast, and designer Wendy Todd’s sets (including the beautifully dressed Irish pub which opens proceedings, and the interior of Martin’s family home) are also delightfully realised.

Photo credit: Andy Rasheed.

Not every aspect of the production excels – a theatrical montage detailing Martin’s expended period of time living rough in a barn with a pack of wild dogs (‘Months and months of sunshine and happiness!’) struggles to convey the passage of time and the complexity of Martin’s life during this period – perhaps unsurprisingly, given that montages are challenging scenes to mount even in cinema. A subsequent sequence featuring the gun-toting farmer Sean Moss also lacks dramatic tension.

Nor are the venue and its acoustics ideal for such an intimate production, though its size was likely dictated by the demands of COVID and socially distanced audiences. Conversely, the placement of a small central stage and Burroughs’ wide-ranging performance throughout the room mean that sooner or later, every audience member is sure to have a ringside seat.

Many stories have been told about overcoming the black dogs of depression and shame, but this sincere and moving production adds something new to the tale. Watching a wiry scruff of a dog defeating a terrifying shadowy hound is remarkable enough. Being motivated by that struggle to overcome one’s own personal demons takes the play to a whole new level.

Slingsby, STCSA and their collaborators have made something magical here; a production that transmutes leaden, real-life misery into theatrical gold.

Rating: 4 stars out of 5 ★★★★

The Boy Who Talked to Dogs

By Amy Conroy

Adapted for the stage from Martin McKenna’s The Boy Who Talked to Dogs

A Slingsby and State Theatre Company SA co-production

Developed with the assistance of Draíocht Arts Centre, Dublin

Directed by Andy Packer

Songwriter: Lisa O’Neill

Composer: Quincy Grant

Set Designer: Wendy Todd

Lighting Designer: Chris Petridis

Costume Designer: Ailsa Paterson

Performed by: Bryan Burroughs, Victoria Falconer, Quincy Grant and Emma Luker

Thomas Edmonds Opera Studio, Adelaide Showground, Wayville

26 February – 14 March 2021

The writer visited Adelaide as a guest of Adelaide Festival.