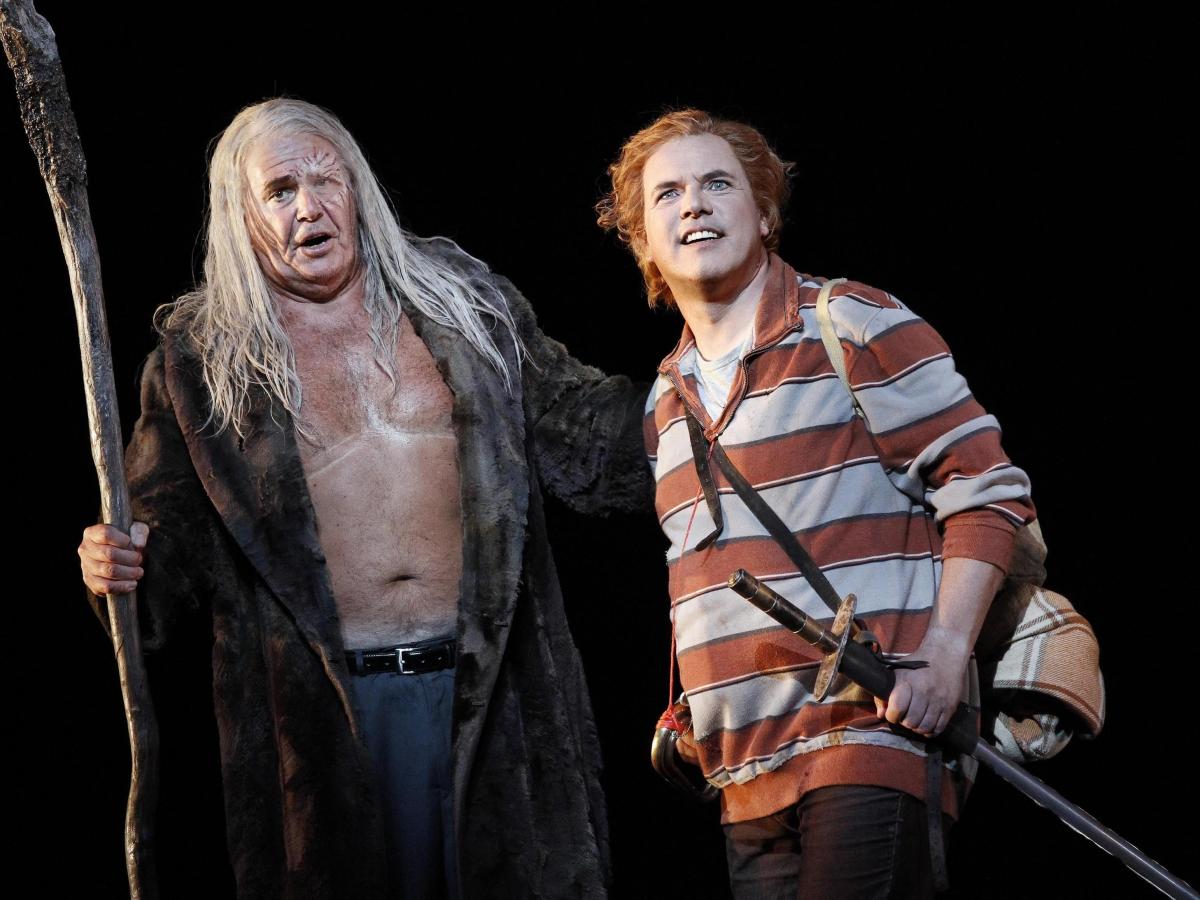

Terje Stensvold as Wotan and Stefan Vinke as Siegfried. Photo: Jeff Busby

In the third of the Ring Des Nibelungen operas, Siegfried director Neil Armfield’s use of ‘playful frames and gestures of the theatre’ is dominated by the use of a false proscenium arch with a cinema like white screen within the State Theatre’s proscenium. In it Mime’s forest forge is furnished with a shabby sofa, bunk beds, a microwave and an electric kettle. As with his updated vision of Das Rheingold the irreverent visual humour quickly gives way to an astonishing appropriateness. Wagner’s bullyboy Siegfried is supposed to enter with a wild bear and set it on Mime. Armfield’s bullyboy is seen from the start on the top bunk surrounded by childish drawings of animals and dragons and making something out of cardboard scraps. It is a bear mask and as the music is cued for his entrance; he springs from the bed wearing it and terrorises Mime.

The entire first act has the same level of ingenuity and playfulness but in act two the playfulness has a darker purpose. Here the proscenium represents the illusion that is theatre and within this illusion the power of the Ring and form shifting tarnhelm proves to be just as illusory.

Instead of turning himself into a dragon Fafner is seen sitting in front of a mirror pasting his face with white clown make up and practicing silent roars and snarls. The only power the helmet has appears to be the power to delude.

All the same the opening of act two, with the sinister low brass accompanying the scene as a naked Jud Arthur as Fafner grimaces into a camera built into the mirror which projects the magnified image, cinema style, is truly disturbing. When he is heard during the act, it is just his voice booming through the entrance to his cave. But when he appears for his fatal confrontation with Siegfried – who knows nothing of fear or the helmet’s magic – we see exactly what Siegfried sees, a naked vulnerable man.

Revisiting a device he used in his production of Janacek’s The Makropulos Case where the final scene sung by the 300 year old heroine was mimed by an elderly actress, Armfield this time has Deborah Humble sing Erda while pushing an elderly woman in a wheelchair. Humble is dressed and veiled in black, suggesting that the wheelchair bound, frail and blind Erda is near death. Longing for sleep that we now imply means the ‘big sleep’ and the seer of the God’s destiny, Erda’s near death makes their impending fate even more compelling.

Humble sings with a fiery intensity in this short scene and Terje Stensvold responds with the same intensity, paving the way for his final scene in the cycle where his singing reaches a pulverising intensity. In this opera Wotan’s scenes are multi-faceted and delineated with the deepest understanding by this truly great singer. Finding a sense of humour in his scene with Mime, a smug confidence in the scene between him and Warwick Fyfe as Alberich, desperation in the exchanges with Erda and then resignation in his final scene with Siegfried.

Although he is missed after that the singing of Setfan Vinke as Siegfried is just as amazing. He sings the long, arduous and tiring role with apparent ease and endless stamina. He is also a terrific actor and brings off the characterisation superbly.

When first seen in act one this Siegfried – just as Wagner wanted only better and more understandable – behaves like a rowdy adolescent with long untreated ADHD. In the forest; however, he sings with a rapt wonder at the natural world and even weeps as he considers his orphaned childhood.

The last half hour of the opera is an extraordinary affair. Pushing through the glittering gold curtain representing the magic fire, Vinke is joined by Susan Bullock’s Brünnhilde for a final duet of superhuman proportions.

The orchestra play magnificently. The strings particularly in the interlude before that final scene are magnificent and add to the intensity of its impact. Armfield’s take on the story was again ‘playful’ but powerful and at times profound.

Five Stars

Further information and ticket availability available at: melbourneringcycle.com.au