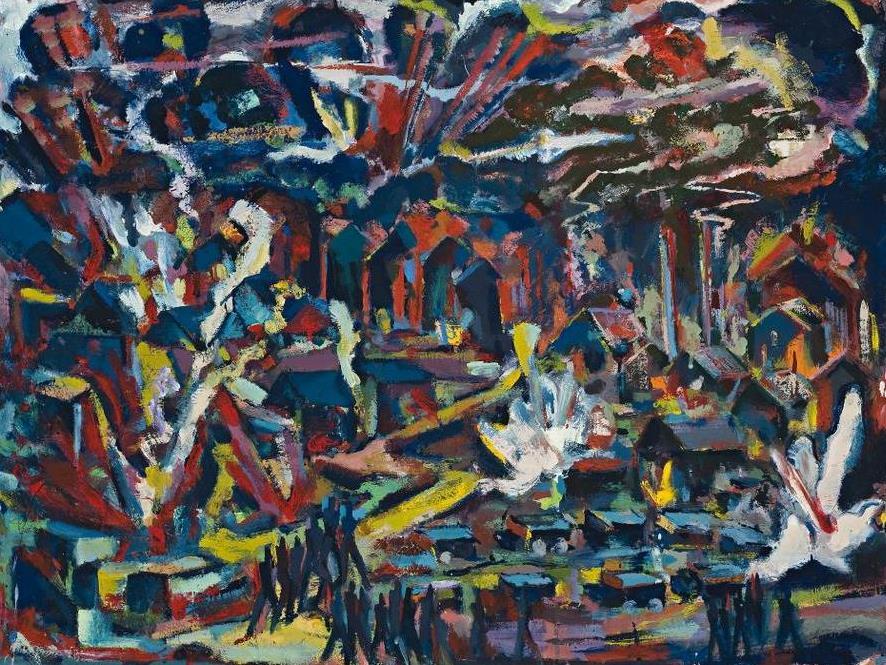

Roger Kemp, War Conception (1941-42).

Our collective memory of war is almost invariably informed by documentary photography rather than objects of fine art. The most iconic images of World War II are all photographs: Churchill’s victory salute, complete with cigar; the emaciated internees of Auschwitz and Changi; and of course, St Paul’s Cathedral enveloped in smoke during the Blitz, a bastion of civilisation against Fascist brutality. Considering the portability, immediacy and perceived accuracy of the camera in the context of war, why bother with brushes and paints? What can painting and sculpture bring to the representation of conflict that photography cannot?

Reality in Flames: modern Australian art and the Second World War neglects to answer these questions, and I suspect that an exhibition of war photography would have been better received. The show is wholly comprised of objects from the Australian War Memorial collection, and contains works by some of Australia’s premier modernists: Russell Drysdale, Sidney Nolan, Albert Tucker, Nora Heysen, Donald Friend, Dorrit Black. Having been shown at Sydney’s SH Ervin Gallery for much of April, the exhibition will shortly open at the New England Regional Art Museum in Armidale. Coinciding with the centenary of the ANZAC, Reality in Flames is most likely intended to elevate the Memorial’s profile beyond Canberra and encourage a more pluralistic approach to the commemoration of war.

There is a great diversity of artistic expression displayed here, and this is the exhibition’s major strength. One of the show’s more intriguing works is Frank Hinder’s Bomber Crash (1949), the artist having served in the Australian Infantry Forces. Upon witnessing the accident that informed this work, Hinder noted in his diary, ‘Before [the] door opened [I] wondered what it would be like to be incinerated.’ But there is nothing so chaotic or visceral in the finished work: Cubo-futurism provides a means of coping with this horrific notion. Hinder has contained the plane’s explosion within an intricate arrangement of curvilinear forms. The composition is devoid of an obvious human presence and the plume of dark smoke that dominates the picture plane is confined to a definite outline.

Eric Thake imbues Cubist-inspired geometric forms with a spooky surrealism in Airstrip at night (1945). The two human subjects of the drawing are represented only by their elongated shadows, which intersect with broad patches of light from an Alice Springs airfield. Thake has raised the horizon to such an extent that the foreground appears flattened and tilted towards the disconcerted viewer.

Roger Kemp’s War Conception (1941-42) appears at first as a brightly coloured exemplar of early Abstract Expressionism; a vibrant patchwork of smudges and smears. Upon closer and prolonged inspection, however, one realises that the work is in fact representational – out of the seemingly innocuous painterly surface, a violent dystopia emerges. Once this scene becomes apparent, the viewer cannot un-see it (would it be vulgar to compare this to the phalluses hidden in Arthur McIntyre’s collages? ) It is a mark of Kemp’s ingenuity as a painter that he is able to render such poignant imagery with remarkable subtlety.

Perplexingly enough, Kemp’s work is referred to as ‘Surrealism’ by the curators (he is broadly considered by art historians to be a ‘transcendental abstractionist’), this revealing the difficulties of attempting to be a catch-all institution as the War Memorial is here. Greater academic rigour is needed if the Memorial is to be taken seriously as an art institution, and it is not enough to group works thematically without much thought as to the aesthetics of it all. One major blunder in this regard is the hanging of a Harold Abbott portrait next to several Tucker works, simply because they depict soldiers bearing physical deformities sustained in conflict. The effect is aesthetically jarring, to say the least.

The pictorial language of war need not be confined to photography. Painting is an imperfect and more human art. As such it is well suited to the remembrance of war. The human mind is not a camera, capturing and reproducing all that is observed. It is fractured and fallible. We wouldn’t wish it otherwise.

Rating: 3 out of 5 stars

Reality in Flames: modern Australian art and the Second World War

An Australian War Memorial travelling exhibition

SH Ervin Gallery, Watson Rd, The Rocks

7 March – 13 April

New England Regional Art Museum, Armidale

24 April – 13 July

Gosford Regional Gallery, Gosford

19 July – 7 September

Rockhampton Regional Art Gallery, Rockhampton

10 October – 30 November

Glasshouse Art, Conference and Exhibition Centre, Port Macquarie

6 February 2015 – 22 March 2015

Perc Tucker Regional Gallery, Townsville

3 April – 24 May 2015

Australian War Memorial

18 June – 18 November 2015