Buying a one-way ticket to Vietnam in the middle of a war is not something I’d personally ever do, but in 1966 that’s exactly what a 21-year-old Catherine Leroy did. She went straight to the frontlines. Her courage brought the war into people’s living rooms, collapsing distance into something uncomfortably close.

One-Way Ticket to Vietnam 1966 –1968: quick links

One-Way Ticket to Vietnam 1966 –1968: part of the 11th Ballarat International Foto Biennale

At a time when photography wasn’t yet democratised, Leroy’s eyes became the eyes of the world. She was one of the first female war photographers of her generation, and now her work sits in a gallery room at Ballarat Town Hall, part of the 11th Ballarat International Foto Biennale.

The show is shaped like a snake coiled onto itself. Panels open at odd angles so you weave in and out, choosing your own path. It’s a clever use of space. The work is cut into three acts: the first years (1966 – 1967), when she embedded with American GIs and army personnel; then, out of nowhere, it ends. Just as suddenly, she reappears in 1980. The break feels abrupt, even awkward – as if whole stories and contexts had been sliced out of view.

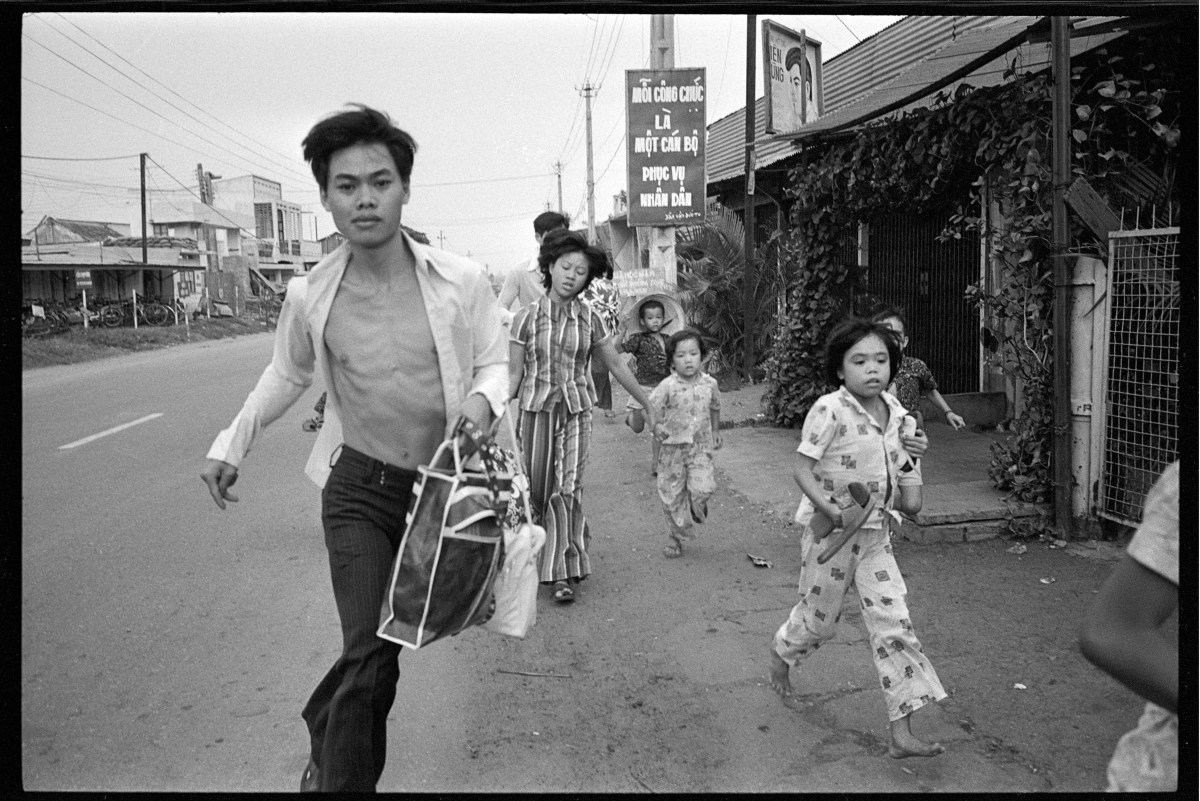

One-Way Ticket to Vietnam 1966 –1968: images lean on familiar tropes

The photographs themselves sit uneasily with this reviewer. Leroy’s bravery is undeniable, but so many of the images lean on familiar tropes: children abandoned, women crying or needing help, men doing the saving, the West cast as the calming force in Eastern chaos. The exhibition seemed more interested in celebrating her courage than interrogating the politics of representation, gender, or the Western gaze in war imagery. And at a time when images of war are everywhere, surely this was a chance to ask harder questions about how such images are made, and what they do to us.

That absence feels sharp in 2025. For those of us who have been relentlessly exposed to images of Gaza for the past two years, it’s impossible not to miss the silence. Why would a festival in this country choose to show a war photographer from the 1960s without drawing lines to the present? With institutions so afraid of losing funding if they speak on Palestine, silence becomes a curatorial choice too.

One-Way Ticket to Vietnam 1966 –1968: risk of reopening wounds

And there’s something else. Here in Victoria, home to one of the largest Vietnamese diasporas outside Vietnam, the exhibition showed no awareness of how these images might land with people whose families lived that war. That lack of cultural sensitivity risks reopening wounds instead of creating dialogue.

In the end, the show missed an opportunity. It could have gone further. Instead of only celebrating Leroy’s courage (and she was courageous!), it might have asked: What do these images of women and children, of men doing all the rescuing, really reinforce? Who gets framed as vulnerable and who as heroic? What does it mean when the West is cast as the steadying force in Eastern chaos? And what responsibility do we have today, in this image-saturated world, to see how these tropes persist?

Read: Troy review: a mythical marvel at the Malthouse

The festival missed its chance to confront how war images still shape our imagination. What silences are we complicit in when we only look back?

One-Way Ticket to Vietnam 1966 – 1968: an exhibition of Catherine Leroy’s photography will be exhibited at the Ballarat International Foto Biennale until 19 October 2025.