At first take, Mostyn Bramley-Moore’s paintings in the main space at Woolloongabba Art Gallery, appear to be ‘happy’, abstract works. (A colleague was heard to use this word at the launch, and I agreed. Standing within earshot and nodding, Bramley-Moore may have been endorsing this thought, or not.)

There’s an initial feeling of elation with these 23 paintings, linked in part to the use of vibrant blocks of red acrylic dominating several of the canvasses. On close attention – and later in conversation with the artist – you know there’s much more to be divined. Not overtly dark things but a deeper narrative.

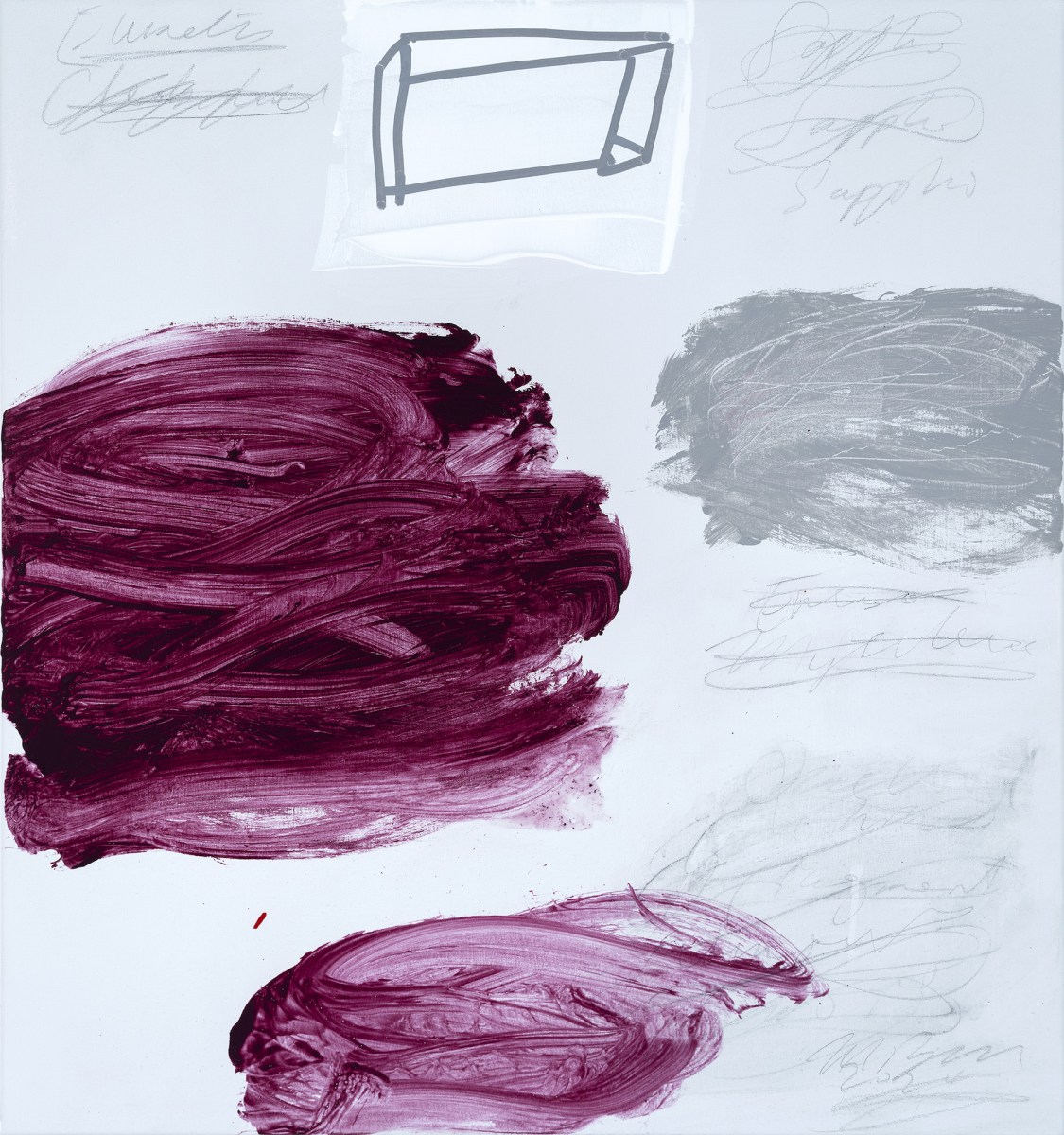

To begin with, the use of red – powerful and versatile – can symbolise love and passion through to danger and anger, and in historical art, blood and hell-fire. The red used by Bramley-Moore ranges from vermillion to crimson, and, when applied thinly by the artist’s hand, the latter is indeed like smeared patches of blood.

He uses vermillion effectively to convey urgency and to be evocative. The titles of these predominantly red canvasses do not generally suggest their subject. For example: Kapulu (2023) references the active volcano Kilauea with its destructive lava flows (which the artist visited when he was an artist in residence at the University of Hawaii in the 1980s); and Phaistos (2024) relates to archaeologist Luigi Pernier’s discovery of a much-debated clay disk (known as the Phaistos Disk) in 1908 in Crete.

Its spiral of impressed symbols have never been convincingly interpreted. ‘I’m not so much interested in the disk itself as I am with people’s fascination with objects like this’, says Bramley-Moore.

Blood is not mentioned in Bramley-Moore’s anecdotes about the paintings where crimson appears: Temple; Sappho and Eumetis; and Cardenio (all from 2024), for example.

It is, however, inferred in the Temple story, as the artist relates: ‘One night in 356 BC a man named Herostratus crept into the Temple of Artemis [one of the seven wonders of the ancient world] in Ephesus and burnt it down … Herostratus thought … he could gain fame. He was caught and executed, and his name was banned from ever being mentioned, but his name lives on.’

Mostyn Bramley-Moore: themes

All of these paintings, while having different themes, are about ‘erasure, palimpsests, cultural loss and the human impulse to reconfigure reality’, as Bramley-Moore puts it.

This gives reason to why the artist, in several paintings, has written lines of cursive text and then crossed them out; cancelled them. He explains: ‘The general area that I’ve been addressing over the last couple of years has been the eternal vulnerability of . . . cultural information. We live in an age of false news, conspiracy theories, the reckless disposal of valuable material . . .’

The title of the exhibition, Stimming, is short for self-stimulating behaviour. It refers to repetitive actions or movements that people make to regulate their sensory input. These actions can include hand-flapping, rocking or repeating sounds.

Once you have this information you appreciate the repetitive actions that Bramley-Moore brings to his painting. But there are other things at play. His process is not compulsive and certainly not out-of-control. While there’s spontaneity and improvisation, there’s also care, thought and design.

It is confident work, strong and consistent, notwithstanding the mood swings that come with colour and design changes: from the red paintings to a series of five, free-flowing blue canvasses (about the wind), as well as works in green. ‘I’ve never tried to stick to any kind of artistic style. I get interested in an idea … and chase it through a series of works using whatever means seems to be effective’, says Bramley-Moore.

Above all, there’s a beguiling gestural freshness and immediacy in all of Bramley-Moore’s paintings; a feeling of the elements, fire and wind in particular, coupled with stories of gods and men.

Mostyn Bramley-Moore: Stimming continues at Woolloongabba Art Gallery until 26 July. Find out more.