The annual festival calendar continues to grow, largely bolstered by new regional festivals sprouting up across Australia. They tap into a desire of contemporary audiences for immersive, genuine experiences – and the multidisciplinary aspect of OpenField delivers on that demand.

While not strictly ‘new’ – OpenField presented its first edition in 2023 – the biennial festival has returned this past weekend to strengthen its vision and brand, despite drizzly weather. With the festival located in the NSW town of Berry (about a two-hour drive from Sydney), the short distance proved again to work for the event, drawing crowds, especially on the Sunday. However, this event is curated to push beyond just day-trippers, with a large dose of the programming at night to encourage that tourist stay and, in turn, community support.

This is both a win and a loss for audience: the win is that the evening program is, in many ways, the pulsing heart of OpenField where visitors and locals rub shoulders, laugh and delight in the experience. While for those just dipping a toe in, it could be read a little thin on the ground. For example, I would have liked to have seen another work paired with Jayanto Tan’s ceramic installation at the CWA Hall – which got a little lost in scale at this venue despite is playful appeal. Similarly, Joan Ross’ video Colonial Grab (2015) – while projected as part of OpenField by Night – also got lost to the majority of festival-goers during the day and was begging to be presented solo and at scale.

That said, what I love about this festival is its walkability – at any time of day. And a great piece this year was Alice McAuliffe’s pavement stencils, which riff off that idea of self-navigated wayfinding, but also echo Regency design and architectural details typical of European colonisation. The action of walking over them almost has a sense of returning agency.

A key aspect of OpenField is its takeovers of local historic buildings with installations, and a highlight among these was Janet Laurence’s poetic video installation The Court Requiem for Nature (2025), which exposed crimes against our environment in the Old Court House, giving nature a voice. It spoke to the calibre of the work on show, but also this thread of soft activism that runs across many of the artworks for OpenField.

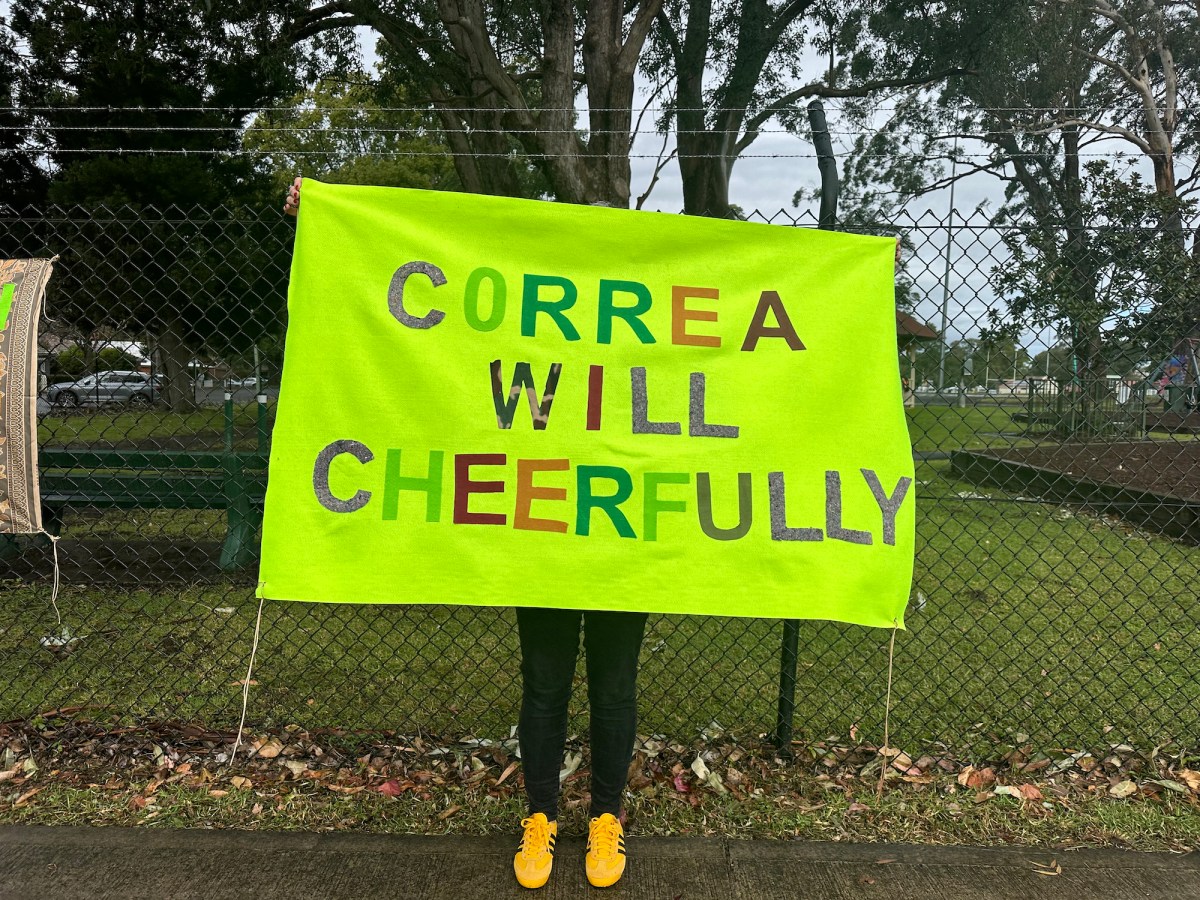

We saw this played out by Rox Deluca’s installation of reclaimed ocean and industrial plastics in the old heritage Rotunda, and Scrub Collective’s wordplay banners focusing on native plants in a participatory project in the old Council Chambers. It was a great demonstration of the power of slow art. The Collective also partnered with Climate Writers in a workshop on crafting compelling letters to politicians.

Another solid work was Harriet Goodall’s kinetic sculpture Counterbalance (2024-25)made from the introduced and invasive plant Giant reed (Arundo donax), choking our native waterways. With the sculpture suspended in the grandstand like a looming creature, visitors were invited to interact with this piece and, through action, encouraged to explore deeper thought on how we might destabilise its pervasiveness.

Further standout works were Elyssa Sykes-Smith’s site-responsive sculpture, Imaginarium Pontem (Latin for ‘Imaginary Bridge’), that seemingly jumped the fence to the CWA, and hinted at the idea of building bridges through community networks.

Then there was Keith Lambert’s performative installation Without a Trace at the Berry School of Arts, drawing and erasing with robotic vacuum cleaners in a comment on the ‘instability of human creativity in a digital age,’ according to Lambert. By night this venue was further transformed into an ever-changing program of cabaret (Bella Louche’s burlesque was the talking point of the weekend), discos, roaming performances, with mention also of a street parade, and a drink and draw session in the local pub, and AUSTI Dance and Physical Theatre’s dance event, Nothing More, using lights on the showground oval, equally defining this festival.

The locally-based curators – Lenka Kripac and Amelia Ramsden – also sensitively included a First Nations Hub with weaving workshops by Amethyst Downing and collaborative story cloak by Jodi Edwards, as well as a salon of local artists diffusing that kind of helicopter talent drop with many festivals, and yet keeping the balance and standard high to draw audiences.

Read: Defining First Nations exhibitions that will shape 2025

When experienced in this very palpable rural setting, OpenField came across as very genuine and delivered a real experience of community to those visiting. Still in its early days, there is room for finessing and expanding, but overall OpenField is definitely one for the diary and a good option in the growing landscape of regional festivals. Its next edition will be presented in June 2027.

OpenField

13-15 June

Berry, NSW

Artistic Director Lenka Kripac

Festival Director Amelia Ramsden

The writer travelled to Berry as a guest of OpenField and Bangalay Luxury Villas.